As (Roman coin)

The as (plural asses), also assarius (rendered into Greek as ἀσσάριον, assarion)[1] was a bronze, and later copper, coin used during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire.

Republican era coinage

The Romans replaced the usage of Greek coins, first by bronze ingots, then by disks known as aes rude.[2] The system thus named as was introduced in ca. 280 BC as a large cast bronze coin during the Roman Republic. The following fractions of the as were also produced: the bes (2/3), semis (1/2), quincunx (5/12), triens (1/3), quadrans (1/4), sextans (1/6), uncia (1/12, also a common weight unit), and semuncia (1/24), as well as multiples of the as, the dupondius (2), sestertius (2.5), tressis (3), quadrussis (4), quinarius (5), denarius (10) and aureus (250).

After the as had been issued as a cast coin for about seventy years, and its weight had been reduced in several stages, a sextantal as was introduced (meaning that it weighed one-sixth of a pound). At about the same time a silver coin, the denarius, was also introduced. Earlier Roman silver coins had been struck on the Greek weight standards that facilitated their use in southern Italy and across the Adriatic, but all Roman coins were now on a Roman weight standard. The denarius, or 'tenner', was at first tariffed at ten asses, but in about 140 B.C. it was retariffed at sixteen asses. This is said to have been a result of financing the Punic Wars.

During the Republic, the as featured the bust of Janus on the obverse, and the prow of a galley on the reverse. The as was originally produced on the libral and then the reduced libral weight standard. The bronze coinage of the Republic switched from being cast to being struck as the weight decreased. During certain periods, no asses were produced at all.

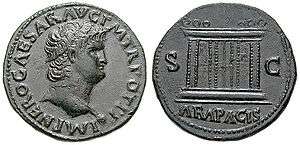

Imperial era coinage

Following the coinage reform of Augustus in 23 BC, the as was struck in reddish pure copper (instead of bronze), and the sestertius or 'two-and-a-halfer' (originally 2.5 asses, but now four asses) and the dupondius (2 asses) were produced in a golden-colored alloy of bronze known by numismatists as orichalcum. The as continued to be produced until the 3rd century AD. It was the lowest valued coin regularly issued during the Roman Empire, with semis and quadrans being produced infrequently, and then not at all by the time of Marcus Aurelius. The last as seems to have been produced by Aurelian between 270 and 275 and at the beginning of the reign of Diocletian.[3]

Byzantine coinage

The as, under its Greek name assarion, was re-established by the Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos (r. 1282–1328) and minted in great quantities in the first half of the 14th century. It was a low-quality flat copper coin, weighing ca. 3–4 grams and forming the lowest denomination of contemporary Byzantine coinage, being exchanged at 1:768 to the gold hyperpyron. It appears that the designs on the assarion changed annually, hence they display great variations. The assarion was replaced in 1367 by two other copper denominations, the tournesion and the follaro.[1][4]

Value in the market

Here are some example salaries and product costs as of the times of Diocletian in the third century AD:

- Farm laborer monthly pay, with meals = 400 asses

- Teacher's monthly pay, per boy = 800 asses

- Barber's service price, per client = 32 asses

- 1 kg of pork = 380 asses (1 lb = 170 asses)

- 1 kg of grapes = 32 asses (1 lb = 15 asses)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to As. |

References

- 1 2 Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, p. 212, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- ↑ Pierre-François Puech (1970-01-01). "Deux As de Nimes au Musée d'Arles : A Roman Coin and the Myth of Anthony and Cleopatra | Pierre-François Puech". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-07.

- ↑ "Aurelian Æ As. Rome mint. IMP AVRELIANVS AVG, laureate and cuirassed bust right / CONCORDIA AVG, Aurelian and Severina clasping hands, radiate bust of Sol, right, above them. RIC 80, Cohen 35. * Sear RCV [1988] s3276 *". Wildwinds.com. Retrieved 2014-06-07.

- ↑ Grierson, Philip (1999), Byzantine coinage (PDF), Dumbarton Oaks, pp. 22, 45, ISBN 978-0-88402-274-9