ArmaLite AR-15

| ArmaLite AR-15 | |

|---|---|

| Type | Automatic rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1959-1990s |

| Wars | Vietnam War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Eugene Stoner and L. James Sullivan[1] |

| Designed | 1956[2] |

| Manufacturer | |

| Produced | 1959-1964[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 6.55 lb (2.97 kg) with 20 round magazine[3] |

| Length | 39 in (991 mm)[3] |

| Barrel length | 20 in (508 mm) |

|

| |

| Cartridge | 5.56×45mm NATO |

| Action | Gas-operated, rotating bolt (direct impingement) |

| Rate of fire | full-auto 750 rounds/min cyclic[3] |

| Muzzle velocity | 3,300 ft/s (1,006 m/s)[3] |

| Effective firing range | 500 yd (457 m) |

| Feed system | 20-round detachable box magazine |

| Sights | Iron sights |

The ArmaLite AR-15 is a selective-fire, 5.56×45mm, air-cooled, direct impingement gas-operated, magazine-fed rifle, with a rotating bolt and straight-line recoil design. It was designed above all else to be a lightweight assault rifle, and to fire a new lightweight, high velocity small caliber cartridge to allow the soldier to carry more ammunition.[4] It was based on the Armalite AR-10 rifle. After modifications (most notably, the charging handle was re-located from under the carrying handle like AR-10 to the rear of the receiver),[5] the new redesigned rifle was subsequently adopted by the United States military as the M16 Rifle, which went into production in March 1964.[4][6] The Armalite AR-15 is the parent of a variety of AR-15 variants.

History

After World War II, the United States military started looking for a single automatic rifle to replace the M1 Garand, M1/M2 Carbines, M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, M3 "Grease Gun" and Thompson submachine gun.[7][8] However, early experiments with select-fire versions of the M1 Garand proved disappointing.[9] During the Korean War, the select-fire M2 Carbine largely replaced the submachine gun in US service[10] and became the most widely used Carbine variant.[11] However, combat experience suggested that the .30 Carbine round was under-powered.[12] American weapons designers concluded that an intermediate round was necessary, and recommended a small-caliber, high-velocity cartridge.[13]

However, senior American commanders having faced fanatical enemies and experienced major logistical problems during WWII and the Korean War,[14][15][16][17][18] insisted that a single powerful .30 caliber cartridge be developed, that could not only be used by the new automatic rifle, but by the new general-purpose machine gun (GPMG) in concurrent development.[19][20] This culminated in the development of the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge and the M14 rifle[19] which was an improved M1 Garand with a 20-round magazine and automatic fire capability.[21][22][23] The U.S. also adopted the M60 general purpose machine gun (GPMG).[19] Its NATO partners adopted the FN FAL and HK G3 rifles, as well as the FN MAG and Rheinmetall MG3 GPMGs.

The first confrontations between the AK-47 and the M14 came in the early part of the Vietnam War. Battlefield reports indicated that the M14 was uncontrollable in full-auto and that soldiers could not carry enough ammo to maintain fire superiority over the AK-47.[21][24] And, while the M2 Carbine offered a high rate of fire, it was under-powered and ultimately outclassed by the AK-47.[25] A replacement was needed: A medium between the traditional preference for high-powered rifles such as the M14, and the lightweight firepower of the M2 Carbine.

As a result, the Army was forced to reconsider a 1957 request by General Willard G. Wyman, commander of the U.S. Continental Army Command (CONARC) to develop a .223 caliber (5.56 mm) select-fire rifle weighing 6 lb (2.7 kg) when loaded with a 20-round magazine.[7] The 5.56mm round had to penetrate a standard U.S. helmet at 500 yards (460 meters) and retain a velocity in excess of the speed of sound, while matching or exceeding the wounding ability of the .30 Carbine cartridge.[26] This request ultimately resulted in the development of a scaled-down version of the ArmaLite AR-10, called ArmaLite AR-15 rifle.[4][5][27]

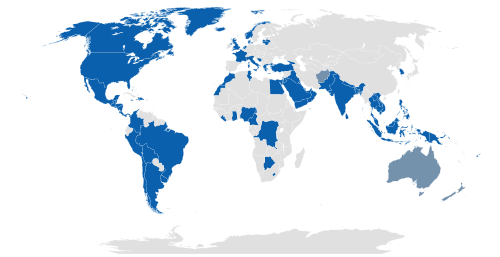

In 1959, ArmaLite sold its rights to the AR-10 and AR-15 to Colt due to financial difficulties.[28] After a Far East tour, Colt made its first sale of Colt made ArmaLite AR-15 rifles to Malaya on September 30, 1959. Colt manufactured their first batch of 300 select-fire Colt ArmaLite AR-15 Model 01 rifles in December 1959.[29] Colt marketed the Colt made ArmaLite AR-15 rifle to various military services around the world.

In July 1960, General Curtis LeMay was impressed by a demonstration of the ArmaLite AR-15. In the summer of 1961, General LeMay was promoted to United States Air Force, Chief of Staff, and requested 80,000 AR-15s. However, General Maxwell D. Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, advised President John F. Kennedy that having two different calibers within the military system at the same time would be problematic and the request was rejected.[30] In October 1961, William Godel, a senior man at the Advanced Research Projects Agency, sent 10 AR-15s to South Vietnam. The reception was enthusiastic, and in 1962, another 1,000 AR-15s were sent.[31] United States Army Special Forces personnel filed battlefield reports lavishly praising the AR-15 and the stopping-power of the 5.56 mm cartridge, and pressed for its adoption.[21]

The damage caused by the 5.56 mm bullet was originally believed to be caused by "tumbling" due to the slow 1 in 14-inch (360 mm) rifling twist rate.[21][30] However, any pointed lead core bullet will "tumble" after penetration in flesh, because the center of gravity is towards the rear of the bullet. The large wounds observed by soldiers in Vietnam were actually caused by bullet fragmentation, which was created by a combination of the bullet's velocity and construction.[32] These wounds were so devastating, that the photographs remained classified into the 1980s.[33]

U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara now had two conflicting views: the ARPA report[34] favoring the AR-15 and the Army's position favoring the M14.[21] Even President Kennedy expressed concern, so McNamara ordered Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance to test the M14, the AR-15 and the AK-47. The Army reported that only the M14 was suitable for service, but Vance wondered about the impartiality of those conducting the tests. He ordered the Army Inspector General to investigate the testing methods used; the Inspector General confirmed that the testers were biased towards the M14.

In January 1963, Secretary McNamara received reports that M14 production was insufficient to meet the needs of the armed forces and ordered a halt to M14 production.[21] At the time, the AR-15 was the only rifle that could fulfill a requirement of a "universal" infantry weapon for issue to all services. McNamara ordered its adoption, despite receiving reports of several deficiencies, most notably the lack of a chrome-plated chamber.[35]

After modifications (most notably, the charging handle was re-located from under the carrying handle like AR-10 to the rear of the receiver),[5] the new redesigned rifle was renamed the Rifle, Caliber 5.56 mm, M16.[4][6] Inexplicably, the modification to the new M16 did not include a chrome-plated barrel. Meanwhile, the Army relented and recommended the adoption of the M16 for jungle warfare operations. However, the Army insisted on the inclusion of a forward assist to help push the bolt into battery in the event that a cartridge failed to seat into the chamber. The Air Force, Colt and Eugene Stoner believed that the addition of a forward assist was an unjustified expense. As a result, the design was split into two variants: the Air Force's M16 without the forward assist, and the XM16E1 with the forward assist for the other service branches.

In November 1963, McNamara approved the U.S. Army's order of 85,000 XM16E1s;[21][36] and to appease General LeMay, the Air Force was granted an order for another 19,000 M16s.[37][38] In March 1964, M16 rifle went into production and the Army accepted delivery of the first batch of 2129 rifles later that year, and an additional 57,240 rifles the following year.[6]

The Colt ArmaLite AR-15 was discontinued with the adoption of the M16 rifle in 1964. Most ArmaLite AR-15 rifles in U.S. service have long ago been upgraded to M16 configuration. The Armalite AR-15 was also used by the United States Secret Service and other U.S. federal law enforcement agencies. Shortly after the United States military adopted the M16 rifle, Colt trademarked the name "AR-15" and has since used it to market its semi-automatic only Colt AR-15 brand of civilian rifles.

In the US, the AR-15 is one of the most well-known firearms in the US, by both by people who don't own firearm and people who do, alongside the Kalashnikov AK-47.

See also

References

- ↑ Ezell, Virginia Hart (November 2001). "Focus on Basics, Urges Small Arms Designer". National Defense. National Defense Industrial Association.

- 1 2 Hogg, Ian V.; Weeks, John S. (2000). Military Small Arms of the 20th Century (7th ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87341-824-9., p. 291

- 1 2 3 4 Rifle Evaluation Study. US Army. Infantry Combat Developments Agency. February 17, 1978

- 1 2 3 4 Kern, Danford Allan (2006). The influence of organizational culture on the acquisition of the m16 rifle. m-14parts.com. A thesis presented to the Faculty of the US Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE, Military History. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

- 1 2 3 Kokalis, Peter G. Retro AR-15. nodakspud.com

- 1 2 3 Report of the M16 rifle review panel. Department of the Army. dtic.mil. 1 June 1968

- 1 2 Major Thomas P. Ehrhart Increasing Small Arms Lethality in Afghanistan: Taking Back the Infantry Half-Kilometer. US Army. 2009

- ↑ The M16. By Gordon Rottman. Osprey Publishing, 2011. page 6

- ↑ http://www.nramuseum.com/media/940585/m14.pdf |CUT DOWN in its Youth, Arguably Americas Best Service Rifle, the M14 Never Had the Chance to Prove Itself. By Philip Schreier, SSUSA, September 2001, p 24-29 & 46

- ↑ Gordon Rottman (2011). The M16. Osprey Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84908-690-5.

- ↑ Leroy Thompson (2011). The M1 Carbine. Osprey Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84908-907-4.

- ↑ Arms of the Chosin Few. Americanrifleman.org. Retrieved on 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Donald L. Hall An effectiveness study of the infantry rifle (PDF). Report No. 593. Ballistic Research Laboratories. Maryland. March 1952 (released 29 March 1973)

- ↑ Fanaticism And Conflict In The Modern Age, by Matthew Hughes & Gaynor Johnson, Frank Cass & Co, 2005

- ↑ "An Attempt To Explain Japanese War Crimes". Pacificwar.org.au. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ "South to the Naktong - North to the Yalu". History.army.mil. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ HyperWar: The Big 'L'-American Logistics in World War II. Ibiblio.org. Retrieved on 2011-12-24.

- ↑ The Logistics of Invasion. Almc.army.mil. Retrieved on 2011-11-23.

- 1 2 3 Col. E. H. Harrison (NRA Technical Staff) New Service Rifle (PDF). June 1957

- ↑ Anthony G Williams. Assault Rifles And Their Ammunition: History and Prospects Archived June 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.. Quarry.nildram.co.uk (revised 3 February 2012). Retrieved on 2011-11-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=2434 Small Arms Review, M14 VS. M16 IN VIETNAM, By Robert Bruce

- ↑ Jane's International Defense Review. Volume 36. Jane's Information Group, 2003. p. 43. "The M14 is basically an improved M1 with a modified gas system and detachable 20-round magazine."

- ↑ M14 7.62mm Rifle. Globalsecurity.org (1945-09-20). Retrieved on 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Lee Emerson M14 Rifle History and Development. 10 October 2006

- ↑ Green Beret in Vietnam: 1957-73. Gordon Rottman. Osprey Publishing, 2002. p. 41

- ↑ Hutton, Robert (ed.), The .223, Guns & Ammo Annual Edition, 1971.

- ↑ Ezell, Edward Clinton (1983). Small Arms of the World. New York: Stackpole Books. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-88029-601-4.

- ↑ http://www.gundigest.com/article/the-ar-16m16-the-rifle-that-was-never-supposed-to-be

- ↑ Dockery, Kevin (2007). Future Weapons. Penguin. p. 56. ISBN 9780425217504.

- 1 2 Rose, p. 372.

- ↑ Rose, pp. 372–373.

- ↑ :: Ammo Oracle. Ammo.ar15.com. Retrieved on 27 September 2011.

- ↑ Rose, p. 373.

- ↑ https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2859676/ARPA-AR-15.pdf RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT FIELD UNIT. Advanced Research Projects Agency. REPORT OF TASK NO. 13A. TEST OF ARMALITE RIFLE. AR-15 (U). 31 July 1962

- ↑ Sweeney, Patrick (28 February 2011). Modern Law Enforcement Weapons & Tactics, 3rd Edition. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-4402-2684-7. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Rose, pp. 380, 392.

- ↑ Ezell, Edward Clinton (1983). Small Arms of the World. New York: Stackpole Books. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-88029-601-4.

- ↑ Rose, p. 380