Arabic grammar

Arabic grammar (Arabic: اَلنَّحْو اَلْعَرَبِي an-naḥw al-‘arabī or قَوَاعِد اَللُّغَة اَلْعَرَبِيَّة qawā‘id al-lughah al-‘arabīyah) is the grammar of the Arabic language. Arabic is a Semitic language and its grammar has many similarities with the grammar of other Semitic languages.

The article focuses both on the grammar of Literary Arabic (i.e. Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic, which have largely the same grammar) and of the colloquial spoken varieties of Arabic. The grammar of the two types is largely similar in its particulars. Generally, the grammar of Classical Arabic is described first, followed by the areas in which the colloquial variants tend to differ (note that not all colloquial variants have the same grammar). The largest differences between the classical/standard and the colloquial Arabic are the loss of grammatical case; a different and strict word order, the loss of the previous system of grammatical mood, along with the evolution of a new system; the loss of the inflected passive voice, except in a few relic varieties; restriction in the use of the dual number and (for most varieties) the loss of the feminine plural.

History

The identity of the oldest Arabic grammarian is disputed; some sources state that it was Abu-Aswad al-Du'ali, who established diacritical marks and vowels for Arabic in the mid-600s, though none of his works have survived.[1] Others have said that the earliest grammarian would have been Ibn Abi Ishaq (died AD 735/6, AH 117).[2]

The schools of Basra and Kufa further developed grammatical rules in the late 8th century with the rapid rise of Islam.[3][4] From the school of Basra, generally regarded as being founded by Abu Amr ibn al-Ala,[5] two representatives laid important foundations for the field: Al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi authored the first Arabic dictionary and book of Arabic prosody, and his student Sibawayh authored the first book on theories of Arabic grammar.[1] From the school of Kufa, Al-Ru'asi is universally acknowledged as the founder, though his own writings are considered lost,[6][7] with most of the school's development undertaken by later authors. The efforts of al-Farahidi and Sibawayh consolidated Basra's reputation as the analytic school of grammar, while the Kufan school was regarding as the guardian of Arabic poetry and Arab culture.[2] The differences were polarizing in some cases, with early Muslim scholar Muhammad ibn `Isa at-Tirmidhi favoring the Kufan school due to its concern with poetry as a primary source.[8]

Early Arabic grammars were more or less lists of rules, without the detailed explanations which would be added in later centuries. The earliest schools were different not only in some of their views on grammatical disputes, but also their emphasis. The school of Kufa excelled in Arabic poetry and exegesis of the Qur'an, in addition to Islamic law and Arab genealogy. The more rationalist school of Basra, on the other hand, focused more on the formal study of grammar.[9]

Division

For classical Arabic grammarians, the grammatical sciences are divided into five branches:

- al-lughah اَللُّغَة (language/lexicon) concerned with collecting and explaining vocabulary.

- at-taṣrīf اَلتَّصْرِيف (morphology) determining the form of the individual words.

- an-naḥw اَلنَّحْو (syntax) primarily concerned with inflection (i‘rāb) which had already been lost in almost all dialects.

- al-ishtiqāq اَلْاِشْتِقَاق (derivation) examining the origin of the words.

- al-balāghah اَلْبَلَاغَة (rhetoric) which elucidates stylistic quality, or eloquence.

The grammar or grammars of contemporary varieties of Arabic are a different question. Said M. Badawi, an expert on Arabic grammar, divided Arabic grammar into five different types based on the speaker's level of literacy and the degree to which the speaker deviated from Classical Arabic. Badawi's five types of grammar from the most colloquial to the most formal are Illiterate Spoken Arabic (عَامِّيَّة اَلْأُمِّيِّين ‘āmmīyat al-ummīyīn), Semi-literate Spoken Arabic (عَامِّيَّة اَلْمُتَنَوِّرِين ‘āmmīyat al-mutanawwirīn), Educated Spoken Arabic (عَامِّيَّة اَلْمُثَقَّفِين ‘āmmīyat al-muthaqqafīn), Modern Standard Arabic (فُصْحَى اَلْعَصْر fuṣḥá al-‘aṣr), and Classical Arabic (فُصْحَى اَلتُّرَاث fuṣḥá at-turāth).[10]

Phonology

Classical Arabic has 28 consonantal phonemes, including two semi-vowels, which constitute the Arabic alphabet.

It also has six vowel phonemes (three short vowels and three long vowels). These appear as various allophones, depending on the preceding consonant. Short vowels are not usually represented in the written language, although they may be indicated with diacritics.

Word stress varies from one Arabic dialect to another. A rough rule for word-stress in Classical Arabic is that it falls on the penultimate syllable of a word if that syllable is closed, and otherwise on the antepenultimate.[11]

Hamzat al-waṣl (هَمْزَة اَلْوَصْل), elidable hamza, is a phonetic object prefixed to the beginning of a word for ease of pronunciation, since literary Arabic doesn't allow consonant clusters at the beginning of a word. Elidable hamza drops out as a vowel, if a word is preceding it. This word will then produce an ending vowel, "helping vowel" to facilitate pronunciation. This short vowel may be, depending on the preceding vowel, a fatḥah (فَتْحَة: ـَ ), pronounced as /a/; a kasrah (كَسْرَة: ـِ ), pronounced as /i/; or a ḍammah (ضَمَّة: ـُ ), pronounced as /u/. If the preceding word ends in a sukūn (سُكُون), meaning that it is not followed by a short vowel, the hamzat al-waṣl assumes a kasrah /i/. The symbol ـّ (شَدَّة shaddah) indicates gemination or consonant doubling. See more in Tashkīl.

Nouns and adjectives

In Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic(MSA), nouns and adjectives are declined, according to case(i‘rāb), state(definiteness), gender and number. In colloquial or spoken Arabic, there are a number of simplifications such as the loss of certain final vowels and the loss of case. A number of derivational processes exist for forming new nouns and adjectives. Adverbs can be formed from adjectives.

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

In Arabic, personal pronouns have 12 forms. In singular and plural, the 2nd and 3rd persons have separate masculine and feminine forms, while the 1st person does not. In the dual, there is no 1st person, and only a single form for each 2nd and 3rd person. Traditionally, the pronouns are listed in the order 3rd, 2nd, 1st.

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | أَنَا anā |

نَحْنُ naḥnu | ||

| 2nd | masculine | أَنْتَ anta |

أَنْتُمَا antumā |

أَنْتُمْ antum |

| feminine | أَنْتِ anti |

أَنْتُنَّ antunna | ||

| 3rd | masculine | هُوَ huwa |

هُمَا humā |

هُمْ hum |

| feminine | هِيَ hiya |

هُنَّ hunna | ||

Informal Arabic tends to avoid the dual forms antumā أَنْتُمَا and humā هُمَا. The feminine plural forms antunna أَنْتُنَّ and hunna هُنَّ are likewise avoided, except by speakers of conservative colloquial varieties that still possess separate feminine plural pronouns.

Enclitic pronouns

Enclitic forms of personal pronouns (اَلضَّمَائِر الْمُتَّصِلَة aḍ-ḍamā’ir al-muttaṣilah) are affixed to various parts of speech, with varying meanings:

- To the construct state of nouns, where they have the meaning of possessive demonstratives, e.g. "my, your, his"

- To verbs, where they have the meaning of direct object pronouns, e.g. "me, you, him"

- To prepositions, where they have the meaning of objects of the prepositions, e.g. "to me, to you, to him"

- To conjunctions and particles like أَنَّ anna "that ...", لِأَنَّ li-anna "because ...", وَ)لٰكِنَّ) (wa)lākinna "but ...", إِنَّ inna (topicalizing particle), where they have the meaning of subject pronouns, e.g. "because I ...", "because you ...", "because he ...". (These particles are known in Arabic as akhawāt inna أَخَوَات إِنَّ (lit. "sisters of inna".)

- If the personal pronoun -ī is added to a word ending in a vowel (e.g. رَأَيْتَ raʼayta "you saw"), an extra -n- is added between the word and the enclitic form to avoid a hiatus between the two vowels (رَأَيْتَـــنِي raʼayta-nī "you saw me").

Most of them are clearly related to the full personal pronouns.

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | ـنِي, ـِي, ـيَ -nī/-ī/-ya |

ـنَا -nā | ||

| 2nd | masculine | ـكَ -ka |

ـكُمَا -kumā |

ـكُمْ -kum |

| feminine | ـكِ -ki |

ـكُنَّ -kunna | ||

| 3rd | masculine | ـهُ, ـهِ -hu/-hi |

ـهُمَا, ـهِمَا -humā/-himā |

ـهُمْ, ـهِمْ -hum/-him |

| feminine | -hā ـهَا | ـهُنَّ, ـهِنَّ -hunna/-hinna | ||

Variant forms

For all but the first person singular, the same forms are used regardless of the part of speech of the word attached to. In the third person masculine singular, -hu occurs after the vowels u or a (-a, -ā, -u, -ū, -aw), while -hi occurs after i or y (-i, -ī, -ay). The same alternation occurs in the third person dual and plural.

In the first person singular, however, the situation is more complicated. Specifically, -nī "me" is attached to verbs, but -ī/-ya "my" is attached to nouns. In the latter case, -ya is attached to nouns whose construct state ends in a long vowel or diphthong (e.g. in the sound masculine plural and the dual), while -ī is attached to nouns whose construct state ends in a short vowel, in which case that vowel is elided (e.g. in the sound feminine plural, as well as the singular and broken plural of most nouns). Furthermore, -ū of the masculine sound plural is assimilated to -ī before -ya (presumably, -aw of masculine defective -an plurals is similarly assimilated to -ay). Examples:

- From كِتَاب kitāb "book", pl. كُتُب kutub: kitāb-ī "my book" (all cases), kutub-ī "my books" (all cases), kitābā-ya "my two books (nom.)", kitābay-ya "my two books (acc./gen.)"

- From كَلِمَة kalimah "word", pl. كَلِمَات kalimāt: كَلِمَتِي kalimat-ī "my word" (all cases), كَلِمَاتِي kalimāt-ī "my words" (all cases)

- From دُنْيَا dunyā "world", pl. دُنْيَيَات dunyayāt: دُنْيَايَ dunyā-ya "my world" (all cases), دُنْيَيَاتِي dunyayāt-ī "my worlds" (all cases)

- From قَاضٍ qāḍin "judge", pl. قُضَاة quḍāh: قَاضِيَّ qāḍiy-ya "my judge" (all cases), قُضَاتِي quḍāt-ī "my judges" (all cases)

- From مُعَلِّم mu‘allim "teacher", pl. مُعَلِّمُون mu‘allimūn: مُعَلِّمِي mu‘allim-ī "my teacher" (all cases), مُعَلِّمِيَّ mu‘allimī-ya "my teachers" (all cases, see above)

- From أَب ab "father": أَبُويَ abū-ya "my father" (nom.) (or is it assimilated?), أَبَايَ abā-ya "my father" (acc.), أَبِيَّ abī-ya "my father" (gen.)

Prepositions use -ī/-ya, even though in this case it has the meaning of "me" (rather than "my"). The "sisters of inna" can use either form (e.g. إِنَّنِي inna-nī or إِنِي inn-ī), but the longer form (e.g. إِنَّنِي inna-nī) is usually preferred.

The second-person masculine plural past tense verb ending -tum changes to the variant form -tumū before enclitic pronouns, e.g. كَتَبْتُمُوهُ katab-tumū-hu "you (masc. pl.) wrote it (masc.)".

Pronouns with prepositions

Some very common prepositions — including the proclitic preposition li- "to" (also used for indirect objects) — have irregular or unpredictable combining forms when the enclitic pronouns are added to them:

| Meaning | Independent form | With "... me" | With "... you" (masc. sg.) | With "... him" |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "to", indirect object | لِـ li- | لِي lī | لَكَ laka | لَهُ lahu |

| "in", "with", "by" | بِـ bi- | بِي bī | بِكَ bika | بِهِ bihi |

| "in" | فِي fī | فِيَّ fīya | فِيكَ fīka | فِيهِ fīhi |

| "to" | إِلَى ilá | إِلَيَّ ilayya | إِلَيْكَ ilayka | إِلَيْهِ ilayhi |

| "on" | عَلَى ‘alá | عَلَيَّ ‘alayya | عَلَيْكَ ‘alayka | عَلَيْهِ ‘alayhi |

| "with" | مَعَ ma‘a | مَعِي ma‘ī | مَعَكَ ma‘aka | مَعَهُ ma‘ahu |

| "from" | مِنْ min | مِنِّي minnī | مِنْكَ minka | مِنْهُ minhu |

| "on", "about" | عَنْ ‘an | عَنِّي ‘annī | عَنْكَ ‘anka | عَنْهُ ‘anhu |

In the above cases, when there are two combining forms, one is used with "... me" and the other with all other person/number/gender combinations. (More correctly, one occurs before vowel-initial pronouns and the other before consonant-initial pronouns, but in Classical Arabic, only -ī is vowel-initial. This becomes clearer in the spoken varieties, where various vowel-initial enclitic pronouns exist.)

Note in particular:

- إِلَى ilá "to" and عَلَى ‘alá "on" have irregular combining forms إِلَيْـ ilay-, عَلَيْـ ‘alay-; but other pronouns with the same base form are regular, e.g. مَعَ ma‘a "with".

- لِـ li- "to" has an irregular combining form la-, but بِـ bi- "in, with, by" is regular.

- مِنْ min "from" and عَنْ ‘an "on" double the final n before -ī. (This should be interpreted as having an irregular stem with doubled n, rather than unexpected use of -nī. This is clear because in the modern spoken varieties, there are other enclitic pronouns beginning with a vowel, and the doubled-n forms occur with them as well, e.g. minnak "from you" (masc. sg.), minnik "from you" (fem. sg.).)

Less formal pronominal forms

In a less formal Arabic, as in many spoken dialects, the endings -ka, -ki, -hu are pronounced as -ak, -ik, -uh, swallowing all short case endings. Short case endings are often dropped even before consonant-initial endings, e.g. kitāb-ka "your book" (all cases), bayt-ka "your house" (all cases), kalb-ka "your dog" (all cases). When this produces a difficult cluster, either the second consonant is vocalized, to the extent possible (e.g. ism-ka "your name", with syllabic m similar to English "bottom"), or an epenthetic vowel is inserted (e.g. isim-ka or ismi-ka, depending on the behavior of the speaker's native variety).

Demonstratives

There are two demonstratives (أَسْمَاء اَلْإِشَارَة asmā’ al-ishārah), near-deictic ('this') and far-deictic ('that'):

| Gender | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | nominative | هٰذَا hādhā |

هٰذَانِ hādhāni |

هٰؤُلَاءِ hā’ulā’i |

| accusative/genitive | هٰذَيْنِ hādhayni | |||

| Feminine | nominative | هٰذِهِ hādhihi |

هٰاتَانِ hātāni | |

| accusative/genitive | هٰاتَيْنِ hātayni | |||

| Gender | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | nominative | ذٰلِكَ، ذَاكَ dhālika, dhāka |

ذٰانِكَ dhānika |

أُولٰئِكَ ulā’ika |

| accusative/genitive | ذَيْنِكَ dhaynika | |||

| Feminine | nominative | تِلْكَ tilka |

تَانِكَ tānika | |

| accusative/genitive | تَيْنِكَ taynika | |||

The dual forms are only used in very formal Arabic.

Some of the demonstratives (hādhā, hādhihi, hādhāni, hādhayni, hā’ulā’i, dhālika, and ulā’ika) should be pronounced with a long ā, although the unvocalised script is not written with alif (ا). Instead of an alif, they have the diacritic ـٰ (dagger alif: أَلِف خَنْجَرِيَّة alif khanjarīyah), which doesn't exist on Arabic keyboards and is seldom written, even in vocalised Arabic.

Qur'anic Arabic has another demonstrative, normally followed by a noun in a genitive construct and meaning 'owner of':

| Gender | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | nominative | ذُو dhū |

ذَوَا dhawā |

ذَوُو، أُولُو dhawū, ulū |

| accusative | ذَا dhā |

ذَوَيْ dhaway |

ذَوِي، أُولِي dhawī, ulī | |

| genitive | ذي dhī | |||

| Feminine | nominative | ذات dhātu |

ذواتا dhawātā |

ذوات، أولات dhawātu, ulātu |

| accusative | ذات dhāta |

ذواتي dhawātay |

ذواتي، أولات dhawāti, ulāti | |

| genitive | ذات dhāti | |||

Note that the demonstrative and relative pronouns were originally built on this word. hādhā, for example, was originally composed from the prefix hā- 'this' and the masculine accusative singular dhā; similarly, dhālika was composed from dhā, an infixed syllable -li-, and the clitic suffix -ka 'you'. These combinations had not yet become completely fixed in Qur'anic Arabic and other combinations sometimes occurred, e.g. dhāka, dhālikum. Similarly, the relative pronoun alladhī was originally composed based on the genitive singular dhī, and the old Arabic grammarians noted the existence of a separate nominative plural form alladhūna in the speech of the Hudhayl tribe in Qur'anic times.

This word also shows up in Hebrew, e.g. masculine זה zeh (cf. dhī), feminine זאת zot (cf. dhāt-), plural אלה eleh (cf. ulī).

Relative pronoun

The relative pronoun is declined as follows:

| Gender | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | nominative | اَلَّذِي alladhī |

اَللَّذَانِ alladhāni |

اَلَّذِينَ alladhīn(a) |

| accusative/genitive | اَللَّذَيْنَ alladhayni | |||

| Feminine | nominative | اَلَّتِي allatī |

اَللَّتَانِ allatāni |

اَللَّاتِي allātī |

| accusative/genitive | اَللَّتَيْنِ allatayni | |||

Note that the relative pronoun agrees in gender, number and case, with the noun it modifies—as opposed to the situation in other inflected languages such as Latin and German, where the gender and number agreement is with the modified noun, but the case marking follows the usage of the relative pronoun in the embedded clause (as in formal English "the man who saw me" vs. "the man whom I saw").

When the relative pronoun serves a function other than the subject of the embedded clause, a resumptive pronoun is required: اَلَّرَجُلُ ٱلَّذِي تَتَكَلَّمْتُ مَعَهُ al-rajul(u) (a)lladhī tatakallamtu ma‘a-hu, literally "the man who I spoke with him".

The relative pronoun is normally omitted entirely when an indefinite noun is modified by a relative clause: رَجُلٌ تَتَكَلَّمْتُ مَعَهُ rajul(un) tatakallamtu ma‘a-h(u) "a man that I spoke with", literally "a man I spoke with him".

Colloquial varieties

The above system is mostly unchanged in the colloquial varieties, other than the loss of the dual forms and (for most varieties) of the feminine plural. Some of the more notable changes:

- The third-person -hi, -him variants disappear. On the other hand, the first person -nī/-ī/-ya variation is preserved exactly (including the different circumstances in which these variants are used), and new variants appear for many forms. For example, in Egyptian Arabic, the second person feminine singular appears either as -ik or -ki depending on various factors (e.g. the phonology of the preceding word); likewise, the third person masculine singular appears variously as -u, -hu, or - (no ending, but stress is moved onto the preceding vowel, which is lengthened).

- In many varieties, the indirect object forms, which appear in Classical Arabic as separate words (e.g. lī "to me", lahu 'to him'), become fused onto the verb, following a direct object. These same varieties generally develop a circumfix /ma-...-ʃ(i)/ for negation (from Classical mā ... shay’ 'not ... a thing', composed of two separate words). This can lead to complicated agglutinative constructs, such as Egyptian Arabic /ma-katab-ha-ˈliː-ʃ/ 'he didn't write it (fem.) to me'. (Egyptian Arabic in particular has many variant pronominal affixes used in different circumstances, and very intricate morphophonemic rules leading to a large number of complex alternations, depending on the particular affixes involved, the way they are put together, and whether the preceding verb ends in a vowel, a single consonant, or two consonants.)

- Other varieties instead use a separate Classical pseudo-pronoun īyā- for direct objects (but in Hijazi Arabic the resulting construct fuses with a preceding verb).

- Affixation of dual and sound plural nouns has largely vanished. Instead, all varieties possess a separate preposition with the meaning of "of", which replaces certain uses of the construct genitive (to varying degrees, depending on the particular variety). In Moroccan Arabic, the word is dyal (also d- before a noun), e.g. l-kitab dyal-i "my book", since the construct-state genitive is mostly unproductive. Egyptian Arabic has bitā‘ , which agrees in gender and number with the preceding noun (feminine bitā‘it/bita‘t, plural bitū‘ ). In Egyptian Arabic, the construct-state genitive is still productive, hence either kitāb-i or il-kitāb bitā‘-i can be used for "my book", but only il-mu‘allimūn bitū‘-i "my teachers".

- The declined relative pronoun has vanished. In its place is an indeclinable particle, usually illi or similar.

- Various forms of the demonstrative pronouns occur, usually shorter than the Classical forms. For example, Moroccan Arabic uses ha l- "this", dak l-/dik l-/duk l- "that" (masculine/feminine/plural). Egyptian Arabic is unusual in that the demonstrative follows the noun, e.g. il-kitāb da "this book", il-binti di "this girl".

- Some of the independent pronouns have slightly different forms compared with their Classical forms. For example, usually forms similar to inta, inti "you (masc./fem. sg.)" occur in place of anta, anti, and (n)iḥna "we" occurs in place of naḥnu.

Numerals

Cardinal numerals

Numbers behave in a quite complicated fashion. wāḥid- "one" and ithnān- "two" are adjectives, following the noun and agreeing with it. thalāthat- "three" through ‘asharat- "ten" require a following noun in the genitive plural, but disagree with the noun in gender, while taking the case required by the surrounding syntax. aḥada ‘asharah "eleven" through tis‘ata ‘asharah "nineteen" require a following noun in the accusative singular, agree with the noun in gender, and are invariable for case, except for ithnā ‘asharah/ithnay ‘ashara "twelve".

The formal system of cardinal numerals, as used in Classical Arabic, is extremely complex. The system of rules is presented below. In reality, however, this system is never used: Large numbers are always written as numerals rather than spelled out, and are pronounced using a simplified system, even in formal contexts.

Example:

- Formal: أَلْفَانِ وَتِسْعُ مِئَةٍ وَٱثْنَتَا عَشَرَةً سَنَةً alfāni wa-tis‘u mi’atin wa-thnatā ‘asharatan sanatan "2,912 years"

- Formal: بَعْدَ أَلْفَيْنِ وَتِسْعِ مِئَةٍ وَٱثْنَتَيْ عَشَرَةً سَنَةً ba‘da alfayni wa-tis‘i mi’atin wa-thnatay ‘asharatan sanatan "after 2,912 years"

- Spoken: بعدَ) ألفين وتسع مئة واثنتا عشرة سنة) (ba‘da) alfayn wa-tis‘ mīya wa-ithna‘shar sana(tan) "(after) 2,912 years"

Cardinal numerals (اَلْأَعْدَاد اَلْأَصْلِيَّة al-a‘dād al-aṣlīyah) from 0-10. Zero is ṣifr, from which the words "cipher" and "zero" are ultimately derived.

- 0 ٠ ṣifr(un) (صِفْرٌ)

- 1 ١ wāḥid(un) (وَاحِدٌ)

- 2 ٢ ithnān(i) (اِثْنَانِ)

- 3 ٣ thalātha(tun) (ثَلَاثَةٌ)

- 4 ٤ arba‘a(tun) (أَرْبَعَةٌ)

- 5 ٥ khamsa(tun) (خَمْسَةٌ)

- 6 ٦ sitta(tun) (سِتّةٌ)

- 7 ٧ sab‘a(tun) (سَبْعَةٌ)

- 8 ٨ thamāniya(tun) (ثَمَانِيَّةٌ)

- 9 ٩ tis‘a(tun) (تسعةٌ)

- 10 ١٠ ‘ashara(tun) (عَشَرَةٌ) (feminine form ‘ashr(un) عَشْرٌ)

The endings in brackets are dropped in less formal Arabic and in pausa. ة (tā’ marbūṭah) is pronounced as simple /a/ in these cases. If a noun ending in ة is the first member of an idafa, the ة is pronounced as /at/, while the rest of the ending is not pronounced.

اِثْنَانِ ithnān(i) is changed to اِثْنَيْنِ ithnayn(i) in oblique cases. This form is also commonly used in a less formal Arabic in the nominative case.

The numerals 1 and 2 are adjectives. Thus they follow the noun and agree with gender.

Numerals 3–10 have a peculiar rule of agreement known as polarity: A feminine referrer agrees with a numeral in masculine gender and vice versa, e.g. thalāthu fatayātin (ثَلَاثُ فَتَيَاتٍ) "three girls". The noun counted takes indefinite genitive plural (as the attribute in a genitive construct).

Numerals 11 and 13–19 are indeclinable for case, perpetually in the accusative. Numbers 11 and 12 show gender agreement in the ones, and 13-19 show polarity in the ones. Number 12 also shows case agreement, reminiscent of the dual. The gender of عَشَر in numbers 11-19 agrees with the counted noun (unlike the standalone numeral 10 which shows polarity). The counted noun takes indefinite accusative singular.

| Number | Informal | Masculine nominative | Masculine oblique | Feminine nominative | Feminine oblique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | aḥada ‘ashar أَحَدَ عَشَر | aḥada ‘ashara | iḥdá ‘ashratan | ||

| 12 | ithnā ‘ashar اِثْنَا عَشَر | ithnā ‘ashara | ithnay ‘ashara | ithnatā ‘ashratan | ithnatay ‘ashratan |

| 13 | thalāthata ‘ashar ثَلَاثَةَ عَشَر | thalāthata ‘ashara | thalātha ‘ashratan | ||

Unitary numbers from 20 on (i.e. 20, 30, ... 90, 100, 1000, 1000000, etc.) behave entirely as nouns, showing the case required by the surrounding syntax, no gender agreement, and a following noun in a fixed case. 20 through 90 require their noun to be in the accusative singular; 100 and up require the genitive singular. The unitary numbers themselves decline in various fashions:

- ‘ishrūna "20" through tis‘ūna "90" decline as masculine plural nouns

- mi’at- "100" (مِئَة or مِائَة) declines as a feminine singular noun

- alf- "1,000" (أَلْف) declines as a masculine singular noun

The numbers 20-99 are expressed with the units preceding the tens. There is agreement in gender with the numerals 1 and 2, and polarity for numerals 3–9. The whole construct is followed by the accusative singular indefinite.

- 20 ‘ishrūna (عِشْرُونَ) (plural of 10)

- 21 wāḥidun wa-‘ishrūna (وَاحِدٌ وَعِشْرُونَ)

- 22 ithnāni wa-‘ishrūna (إِثْنَانِ وَعِشْرُونَ)

- 23 thalāthatu wa-‘ishrūna (ثَلَاثَةُ وَعِشْرُونَ)

- 30 thalāthūna (ثَلَاتُونَ)

- 40 arba‘ūna (أَرْبَعُونَ)

mi’at- "100" and alf- "1,000" can themselves be modified by numbers (to form numbers such as 200 or 5,000) and will be declined appropriately. For example, mi’atāni "200" and alfāni "2,000" with dual endings; thalāthatu ālāfin "3,000" with alf in the plural genitive, but thalāthu mi’atin "300" since mi’at- appears to have no plural.

In compound numbers, the number formed with the last two digits dictates the declension of the associated noun, e.g. 212, 312, and 54,312 would all behave like 12.

Large compound numbers can have, e.g.:

- أَلْفٌ وَتِسْعُ مِئَةٍ وَتِسْعُ سِنِينَ alfun wa-tis‘u mi’atin wa-tis‘u sinīna "1,909 years"

- بَعْدَ أَلْفٍ وَتِسْعِ مِئَةٍ وَتِسْعِ سِنِينَ ba‘da alfin wa-tis‘i mi’atin wa-tis‘i sinīna "after 1,909 years"

- أَرْبَعَةٌ وَتِسْعُونَ أَلْفاً وَثَمَانِي مِئَةٍ وَثَلَاثٌ وَسِتُّونَ سَنَةً arba‘atun wa-tis‘ūna alfan wa-thamānī mi’atin wa-thalāthun wa-sittūna sanatan "94,863 years"

- بَعْدَ أَرْبَعَةٍ وَتِسْعِينَ أَلْفاً وَثَمَانِي مِئَةٍ وَثَلَاثٍ وَسِتِّينَ سَنَةً ba‘da arba‘atin wa-tis‘īna alfan wa-thamānī mi’atin wa-thalāthin wa-sittīna sanatan "after 94,863 years"

- اِثْنَا عَشَرَ أَلْفاً وَمِئَتَانِ وَٱثْنَتَانِ وَعِشْرُونَ سَنَةً iṯnā ‘ašara alfan wa-mi’atāni wa-thnatāni wa-‘ishrūna sanatan "12,222 years"

- بَعْدَ ٱثْنَيْ عَشَرَ أَلْفاً وَمِئَتَيْنِ وَٱثْنَتَيْنِ وَعِشْرُونَ سَنَةً ba‘da thnay ‘ashara alfan wa-mi’atayni wa-thnatayni wa-‘ishrīna sanatan "after 12,222 years"

- اِثْنَا عَشَرَ أَلْفاً وَمِئَتَانِ وَٱثْنَتَانِ سَنَتَانِ ithnā ‘ashara alfan wa-mi’atāni wa-sanatāni "12,202 years"

- بَعْدَ ٱثْنَيْ عَشَرَ أَلْفاً وَمِئَتَيْنِ وَٱثْنَتَيْنِ سَنَتَيْنِ ba‘da thnay ‘ashara alfan wa-mi’atayni wa-sanatayni "after 12,202 years"

Note also the special construction when the final number is 1 or 2:

- alfu laylatin wa-laylatun "1,001 nights"

أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌٌ

- mi’atu kutubin wa-kitābāni "102 books"

مِائَةُ كُتُبٍ وَكِتَابَانِ

Fractions

Fractions of a whole smaller than "half" are expressed by the structure fi‘l (فِعْل) in the singular, af‘āl (أَفْعَال) in the plural.

- half niṣfun (نِصْفٌ)

- one-third thulthun (ثُلْثٌ)

- two-thirds thulthāni (ثُلْثَانِ)

- one-fourth rub‘un (رُبْعٌ)

- three-fourths thalāthatu arbā‘in (ثَلَاثَةُ أَرْبَاعٍ)

- etc.

Ordinal numerals

Ordinal numerals (الأعداد الترتيبية al-a‘dād al-tartībīyah) higher than "second" are formed using the structure fā‘ilun, fā‘ilatun, the same as active participles of Form I verbs:

- m. أَوَّلُ awwalu, f. أُولَى ūlá "first"

- m. ثَانٍ thānin (definite form: اَلثَّانِيُ al-thānī), f. ثَانِيَةٌ thāniyatun "second"

- m. ثَالِثٌ thālithun, f. ثَالِثَةٌ thālithatun "third"

- m. رَابِعٌ rābi‘un, f. رَابِعَةٌ rābi‘atun "fourth"

- m. خَامِسٌ khāmisun, f. خَامِسَةٌ khāmisatun "fifth"

- m. سَادِسٌ sādisun, f. سَادِسَةٌ sādisatun "sixth"

- m. سَابِعٌ sābi‘un, f. سَابِعَةٌ sābi‘atun "seventh"

- m. ثَامِنٌ thāminun, f. ثَامِنَةٌ thāminatun "eighth"

- m. تَاسِعٌ tāsi‘un, f. تَاسِعَةٌ tāsi‘atun "ninth"

- m. عَاشِرٌ ‘āshirun, f. عَاشِرَةٌ ‘āshiratun "tenth"

They are adjectives, hence there is agreement in gender with the noun, not polarity as with the cardinal numbers. Note that "sixth" uses a different, older root than the number six.

Verbs

Arabic verbs (فعل fi‘l), like the verbs in other Semitic languages, are extremely complex. Verbs in Arabic are based on a root made up of three or four consonants (called a triliteral or quadriliteral root, respectively). The set of consonants communicates the basic meaning of a verb, e.g. k-t-b 'write', q-r-’ 'read', ’-k-l 'eat'. Changes to the vowels in between the consonants, along with prefixes or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as tense, person and number, in addition to changes in the meaning of the verb that embody grammatical concepts such as mood (e.g. indicative, subjunctive, imperative), voice (active or passive), and forms such as causative, intensive, or reflexive.

Since Arabic lacks an auxiliary verb "to have", constructions using li-, ‘inda, and ma‘a with the pronominal suffixes are used to describe possession. For example: عنده بيت (ʿindahu bayt) - literally: With him (is) a house. → He has a house.

Prepositions

| Arabic | English | |

|---|---|---|

| True prepositions |

بـ bi- | with; in, at |

| تـ ta- | Only used in the expression تٱللهِ Tallāhi; "I swear God" | |

| لَـ la- | certainly (also used before verbs) | |

| لِـ li- | to, for | |

| كـ ka- | like, as | |

| إِلَى ’ilá | to, towards | |

| حَتَّى ḥattá | until, up to | |

| عَلَى ‘alá | on, over; against | |

| عَن ‘an | from, about | |

| فِي fī | in, at | |

| مِن min | from; than | |

| مُنْذُ mundhu | ago, since...ago, for (a period of time) | |

| Semi-prepositions | أَمامَ ’amāma | in front of |

| بَيْنَ bayna | between, among | |

| تَحْتَ taḥta | under, below | |

| حَوْلَ ḥawla | around; about | |

| خارِجَ khārija | outside | |

| خِلالَ khilāla | during | |

| داخِلَ dākhila | inside | |

| دُونَ dūna | without | |

| ضِدَّ ḍidda | against | |

| عَنْدَ ‘inda | on the part of; at; at the house of; in the possession of | |

| فَوْقَ fawqa | above | |

| مَعَ ma‘a | with | |

| مِثْلَ mithla | like | |

| وَراءَ warā’a | behind |

There are two types of prepositions, based on whether they arise from the triconsonantal roots system or not. There are ten 'true prepositions' (حُرُوف اَلْجَرّ ḥurūf al-jarr) that do not stem from the triconsonantal roots. These true prepositions cannot have prepositions preceding them, in contrast to the derived triliteral prepositions. True prepositions can also be used with certain verbs to convey a particular meaning. For example, بَحَثَ baḥatha means "to discuss" as a transitive verb, but can mean "to search for" when followed by the preposition عَنْ ‘an, and "to do research about" when followed by فِي fī.

The prepositions arising from the triliteral root system are called "adverbs of place and time" in the native tradition (ظُرُوف مَكَان وَظُرُوف زَمَان ẓurūf makān wa-ẓurūf zamān) and work very much in the same way as the 'true' prepositions.[12]

A noun following a preposition takes the genitive case. However, prepositions can take whole clauses as their object too if succeeded by the conjunctions أَنْ ’an or أَنَّ ’anna, in which case the subject of the clause is in the nominative or the accusative respectively.

The word مَعَ - preposition (حَرْف) or noun (اِسْم)?

This is a question that does not have a clear answer: A حَرْف is by definition مَبْنِيّ, which means that it always (no matter what position or case) stays the same; e.g., the word فِي.[13]

There is a debate going on but most grammarians think that مَعَ 'with' is an اِسْم because the word مَعَ can sometimes have nunation (تَنْوِين). For example, in the expression They came together: جاؤوا مَعًا. That is why مَعَ is occasionally listed under "semi-prepositions," as مَعَ treated as an اِسْم is grammatically speaking a ظَرْف مَكَان or زَمَان (adverb of time or place), so called: اِسْم لِمَكَان الاِصْطِحَاب أَوْ وَقْتَهُ.[14]

Syntax

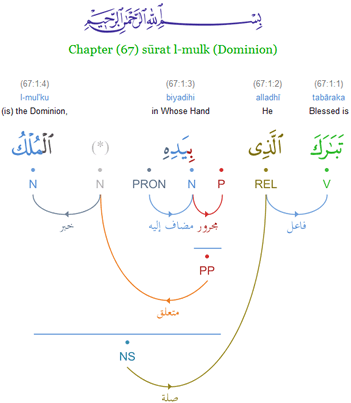

Genitive construction (iḍāfah)

A noun may be defined more closely by a subsequent noun in the genitive. The phrase consisting of a noun and a genitive is known as إِضَافَة iḍāfah, literally "addition". The relation is hierarchical; the first term (اَلْمُضَاف al-muḍāf "the thing added") governs the second term (اَلْمُضَاف إِلَيْهِ al-muḍāf ilayhi "the thing added to"), e.g. بَيْتُ رَجُلٍ baytu rajulin "the house of a man", "a man's house"; بَيْتُ ٱلرَّجُلِ baytu r-rajuli "the house of the man", "the man's house". The construction as a whole represents a nominal phrase, the state of which is inherited from the state of the second term. The first term must be in the construct state; i.e., it must not carry either the definite article or nunation (a final -n). Genitive constructions of multiple terms are possible, and in such cases, all but the final term take the construct state, and all but the first member take the genitive case. When using a pronunciation that generally omits cases (’i‘rāb), the ة (tā’ marbūṭah) of any term in the construct state must always be pronounced with a -t (after /a/) when spoken, e.g. خَالَة أَحْمَد khālat ’aḥmad "Ahmad's aunt". Furthermore, nothing (except a demonstrative determiner) can appear between the two nouns in this construction; if an adjective modifier the first noun, it appears after the second noun e.g. خَالَةُ أَحْمَدَ كَبِيرَةٌ khālatu ’aḥmada kabīratun "Ahmad's old aunt".

This construction is typical for a Semitic language. Formally, the idafah construction consists of two or more nouns strung together to form a relationship of possession or belonging, content in the case of container words (فِنْجَانُ قَهْوَةٍ finjānu qahwatin "a cup of coffee"), and sometimes material (خَاتَمُ خَشَبٍ khātamu khashabin "a wooden ring, ring made of wood"). It is typically equivalent to the English construction "(noun) of (noun)". In many cases the two members become a fixed coined phrase, the idafah being used as the equivalent of a compound noun used in some Indo-European languages such as English. بَيْتُ ٱلطَّلَبَةِ baytu al-ṭalabati thus may mean either "house of the (certain, known) students" or "the student hostel".

Idafah constructions can be considered indefinite or definite only as a whole, something important for adjectival agreement as this determines whether they appear with an article. An idafah construction is definite if the second (or modifier) noun is definite, by having the article or being the proper name of a place or person. The construction is indefinite if it the second noun is indefinite.

- فُرْشَاةُ أَسْنَانٍ furshātu ’asnānin "a toothbrush"

- فُرْشَاةُ أَسْنَانٍ كَبِيرَةٌ furshātu ’asnānin kabīratun "a big toothbrush"

- فُرْشَاةُ ٱلْأَسْنَانِ furshātu l-’asnāni "the toothbrush"

- فُرْشَاةُ ٱلْأَسْنَانِ ٱلْكَبِيرَةٌ furshātu l-’asnāni l-kabīratu "the big toothbrush"

- مَدِينَةُ شِيكَاغُو madīnatu shīkāgho "City of Chicago, the city of Chicago"

- مَدِينَةُ شِيكَاغُو ٱلْكَبِيرَةُ madīnatu shīkāgho l-kabīratu "the big city of Chicago"

The expression of an indefinite possessed noun with said definite possessors is handled with another construction, using a preposition such as لـِـ li-.[15]

- بَيْتُ مُحَمَّدٍ اَلْكَبِيرُ baytu muḥammadin al-kabīru "Muhammad's big house, the big house of Muhammad" (idafah)

- بَيْتُ كَبِيرٌ لِمُحَمَّدٍ baytun kabīrun li-muḥammadin "a big house of Muhammad's" (construction with li-)

The possessive suffix can also take the place of the second noun of an iḍāfah construction, in which case it would also be considered definite. Indefinite possessed nouns are also expressed via a preposition.

- صَدِيقَتُهَا ṣadīqatu-hā "her friend"

- صَدِيقَتُهَا ٱلْجَدِيدَةُ ṣadīqatu-hā l-jadīdatu "her new friend"

- صَدِيقَةُ لَهَا ṣadīqatun la-hā "a friend of hers"

- صَدِيقَةٌ جَدِيدَةٌ لَهَا ṣadīqatun jadīdatun la-hā "a new friend of hers"

Word order

Classical Arabic tends to prefer the word order VSO (verb before subject before object) rather than SVO (subject before verb). Verb initial word orders like in Classical Arabic are relatively rare across the world's languages, occurring only in a few language families including Austronesian, and Mayan. The alternation between VSO and SVO word orders in Arabic results in an agreement asymmetry: the verb shows person, number, and gender agreement with the subject in SVO constructions but only gender (and possibly person) agreement in VSO, to the exclusion of number.[16]

Full agreement: SVO order [17] اَلْمُعَلِّمُونَ قَرَؤُوا ٱلْكِتَابَ al-mu‘allimūna qara’ū l-kitāba the-teachers-M.PL.NOM read.PAST-3.M.PL the-book-ACC 'The (male) teachers read the book.' اَلْمُعَلِّمَاتُ قَرَأْنَ ٱلْكِتَابَ al-mu‘allimātu qara’na l-kitāba the-teachers-F.PL-NOM read.PAST-3.F.PL the-book-ACC 'The (female) teachers read the book.' Partial agreement: VSO order قَرَأَ ٱلْمُعَلِّمُونَ ٱلْكِتَابَ qara’a al-mu‘allimūna l-kitāba read.PAST-3M.SG the-teacher-M.PL.NOM the-book-ACC 'The (male) teachers read the book.' قَرَأْتُ ٱلْمُعَلِّمَاتُ ٱلْكِتَابَ qara’at al-mu‘allimātu al-kitāba read.PAST-3.F.SG the-teacher-F.PL-NOM the-book-ACC 'The (female) teachers read the book.'

Despite the fact that the subject in the latter two above examples is plural, the verb lacks plural marking and instead surfaces as if it was in the singular form.

Though early accounts of Arabic word order variation argued for a flat, non-configurational grammatical structure,[18][19] more recent work[17] has shown that there is evidence for a VP constituent in Arabic, that is, a closer relationship between verb and object than verb and subject. This suggests a hierarchical grammatical structure, not a flat one. An analysis such as this one can also explain the agreement asymmetries between subjects and verbs in SVO versus VSO sentences, and can provide insight into the syntactic position of pre- and post-verbal subjects, as well as the surface syntactic position of the verb.

In the present tense, there is no overt copula in Arabic. In such clauses, the subject tends to precede the predicate, unless there is a clear demarcating pause between the two, suggesting a marked information structure.[17] It is a matter of debate in Arabic literature whether there is a null present tense copula which syntactically precedes the subject in verbless sentences, or whether there is simply no verb, only a subject and predicate.[20][21][22][23][24][25]

Subject pronouns are normally omitted except for emphasis or when using a participle as a verb (participles are not marked for person). Because the verb agrees with the subject in person, number, and gender, no information is lost when pronouns are omitted. Auxiliary verbs precede main verbs, prepositions precede their objects, and nouns precede their relative clauses.

Adjectives follow the noun they are modifying, and agree with the noun in case, gender, number, and state: For example, بِنْتٌ جَمِيلَةٌ bintun jamīlatun 'a beautiful girl' but اَلْبِنُتُ ٱلْجَمِيلَةُ al-bintu al-jamīlatu 'the beautiful girl'. (Compare اَلْبِنْتُ جَمِيلَةٌ al-bintu jamīlatun 'the girl is beautiful'.) Elative adjectives, however, usually don't agree with the noun they modify, and sometimes even precede their noun while requiring it to be in the genitive case.

’inna

The subject of a sentence can be topicalized and emphasized by moving it to the beginning of the sentence and preceding it with the word إِنَّ inna 'indeed' (or 'verily' in older translations). An example would be إِنَّ ٱلسَّمَاءَ زَرْقَاءُ inna s-samā’a zarqā’(u) 'The sky is blue indeed'.

’Inna, along with its related terms (or أَخَوَات ’akhawāt "sister" terms in the native tradition) أَنَّ anna 'that' (as in "I think that ..."), inna 'that' (after قَالَ qāla 'say'), وَلٰكِنَّ (wa-)lākin(na) 'but' and كَأَنَّ ka-anna 'as if' introduce subjects while requiring that they be immediately followed by a noun in the accusative case, or an attached pronominal suffix.

Definite article

As a particle, al- does not inflect for gender, number, person, or grammatical case. The sound of the final -l consonant, however, can vary; when followed by a sun letter such as t, d, r, s, n and a few others, it is replaced by the sound of the initial consonant of the following noun, thus doubling it. For example: for "the Nile", one does not say al-Nīl, but an-Nīl. When followed by a moon letter, like m-, no replacement occurs, as in al-masjid ("the mosque"). This affects only the pronunciation and not the spelling of the article.

Dynasty or family

Some people, especially in Arabia region, when descendant of a famous ancestor, start their last name with آل, an arabic noun which means "family" or "clan", like the dynasty Al Saud (family of Saud) or Al ash-Sheikh (family of the Sheikh). آل is distinct from the definite article ال.

| Arabic | meaning | transcription | example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ال | the | al- | Maytham al-Tammar |

| آل | family/clan of | Al, Aal | Bandar bin Abdulaziz Al Saud |

| أهل | tribe/people of | Ahl | Ahl al-Bayt |

Other

Object pronouns are clitics and are attached to the verb; e.g., أَرَاهَا arā-hā 'I see her'. Possessive pronouns are likewise attached to the noun they modify; e.g., كِتَابُهُ kitābu-hu 'his book'. The definite article اَلـ al- is a clitic, as are the prepositions لِـ li- 'to' and بِـ bi- 'in, with' and the conjunctions كَـ ka- 'as' and فَـ fa- 'then, so'.

Reform

An overhaul of the systematic categorization of Arabic grammar was first suggested by the medieval philosopher al-Jāḥiẓ, though it was not until two hundred years later when Ibn Maḍāʾ wrote his Refutation of the Grammarians that concrete suggestions regarding word order and linguistic governance were made.[26] In the modern era, Egyptian litterateur Shawqi Daif renewed the call for a reform of the commonly used description of Arabic grammar, following trends in Western linguistics instead.[27]

See also

- Arabic language

- List of Arabic dictionaries

- I‘rab

- Literary Arabic

- Varieties of Arabic

- Arabic alphabet

- Quranic Arabic Corpus

- Romanization of Arabic

- Wiktionary: appendix on Arabic verbs

- WikiBook: Learn Arabic

- Sibawayh

- Ibn Adjurrum

- Ajārūmīya

- Ibn Malik

- Alfiya

References

- 1 2 Kojiro Nakamura, "Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians." Orient, v. 10, pgs. 89-113. 1974

- 1 2 Monique Bernards, "Pioneers of Arabic Linguistic Studies." Taken from In the Shadow of Arabic: The Centrality of Language to Arabic Culture, pg. 213. Ed. Bilal Orfali. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2011. ISBN 9789004215375

- ↑ Goodchild, Philip. Difference in Philosophy of Religion, 2003. Page 153.

- ↑ Archibald Sayce, Introduction to the Science of Language. Pg. 28, 1880.

- ↑ al-Aṣmaʿī at the Encyclopædia Britannica Online. ©2013 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. Accessed 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 5, pg. 174, fascicules 81-82. Eds. Clifford Edmund Bosworth, E. van Donzel, Bernard Lewis and Charles Pellat. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1980. ISBN 9789004060562

- ↑ Arik Sadan, The Subjunctive Mood in Arabic Grammatical Thought, pg. 339. Volume 66 of Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2012. ISBN 9789004232952

- ↑ "Sibawayh, His Kitab, and the Schools of Basra and Kufa." Taken from Changing Traditions: Al-Mubarrad's Refutation of Sībawayh and the Subsequent Reception of the Kitāb, pg. 12. Volume 23 of Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics. Ed. Monique Bernards. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9789004105959

- ↑ Sir Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, pg. 350. Leiden: Brill Archive, 1954. New edition 1980.

- ↑ Alaa Elgibali and El-Said M. Badawi. Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said M. Badawi, 1996. Page 105.

- ↑ Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997), p. 90.

- ↑ Ryding, Karin C. (2005). A reference grammar of Modern Standard Arabic (6th printing ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University press. p. 366. ISBN 978-0521777711.

- ↑ Drissner, Gerald (2015). Arabic for Nerds. Berlin, Germany: createspace. p. 64. ISBN 978-1517538385.

- ↑ Drissner, Gerald (2015). Arabic for Nerds. Berlin, Germany: createspace. p. 65. ISBN 978-1517538385.

- ↑ J. A. Haywood, H. M. Nahmad. A New Arabic Grammar of the Written Language. Pages 36-37.

- ↑ Benmamoun, Elabbas 1992. “Structural conditions on agreement.” Proceedings of NELS (North-Eastern Linguistic Society) 22: 17-32.

- 1 2 3 Benmamoun, Elabbas. 2015. Verb-initial orders, with a special emphasis on Arabic. Syncom, 2 edition

- ↑ Bakir, Murtadha. 1980. Aspects of clause structure in Arabic. Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington.

- ↑ Fassi Fehri, Abdelkader. 1982. Linguistique Arabe: Forme et Interprétation. Rabat, Morocco, Publications de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines.

- ↑ Jelinek, Eloise. 1981. On Defining Categories: Aux and Predicate in Egyptian Colloquial Arabic. Doctoral dissertation. University of Arizona, Tucson.

- ↑ Fassi Fehri, Abdelkader. 1993. Issues in the Structure of Arabic Clauses and Words. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- ↑ Shlonsky, Ur 1997. Clause Structure and Word order in Hebrew and Arabic: An Essay in Comparative Semitic Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Heggie, Lorie. 1988. The Syntax of Copular Structures. Doctoral dissertation. USC, Los Angeles.

- ↑ Benmamoun, Elabbas. 2000. The Feature Structure of Functional Categories: A Comparative Study of Arabic Dialects. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Aoun, Joseph, Elabbas Benmamoun, and Lina Choueiri. 2010. The Syntax of Arabic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Shawqi Daif, Introduction to Ibn Mada's Refutation of the Grammarians (Cairo, 1947), p. 48.

- ↑ "The Emergency of Modern Standard Arabic," by Kees Versteegh. Taken from The Arabic Language by permission of the Edinburgh University Press. 1997.

External links

- [ Arabic Grammar through the Quran]

- learn arabic grammar

- consult or download Wright's Arabic Grammar

- Arabic Grammar: Paradigms, Literature, Exercises and Glossary By Albert Socin

- A Practical Arabic Grammar, Part 1

- Einleitung in das studium der arabischen grammatiker: Die Ajrūmiyyah des Muh'ammad bin Daūd By Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad Ibn Ājurrūm

- Alexis Neme and Eric Laporte (2013) Pattern-and-root inflectional morphology: the Arabic broken plural |year=2013

- Alexis Neme (2011), A lexicon of Arabic verbs constructed on the basis of Semitic taxonomy and using finite-state transducers

- Alexis Neme and Eric Laporte (2015), Do computer scientists deeply understand Arabic morphology? - هل يفهم المهندسون الحاسوبيّون علم الصرف فهماً عميقاً؟, available also in Arabic, Indonesian, French