Antitheatricality

Antitheatricality refers to enmity expressed against theater and theater-making artists. At the height of theater's popularity in a historical epoch, antitheatrical feeling is often concurrently also present.[1][2]:435 Other terms used are anti-theatricalism, or antitheatrical prejudice, employed by Jonas Barish.[3]

In many Western languages acting, theatricality, operatic, melodramatic, and 'making a spectacle of oneself' have negative, hostile, or belittling connotations. In French, juste la comédie is dismissive of a theatrical action.[1]:1

Barish argues from theater's ability to stir enjoyment, incite potentially problematic action, to wrestle with problems stemming from the act of mimesis, and from a distrust of the profession of acting.[1] In his book Antitheatrical Prejudice, he intended to prove that "The durability of the prejudice would seem to reflect a basic attitude toward the lives of men in society that deserves to be disengaged and clarified... The ultimate hope [of the book] is to illuminate if possible the nature of the theatrical, and hence, inevitably, of the human."[1]:4 On the other hand, Eileen Fisher finds matters of the antitheatrical to be "internal spats, self criticism from theater practitioners and fine critics. Such 'prejudices' are usually based upon aesthetic dismay at our theaters' rampant commercialism, general triteness, boring star-system narcissism, and overreliance on Broadway-style spectacle and razzmatazz."[2]:435

Plato and ancient Greece

Plato's The Republic

The importance of Greek drama to ancient Greek culture in general was expressed in The Frogs by Aristophanes.[4] In Plato's view, however, expressed in The Republic, acting is a special if leading case of mimesis. Mimesis is regarded as suspect, for its power over man's formative mind. A stage actor must then "be prohibited from miming illiberal or base characters, lest they receive taint from them. They must not imitate women either, or slaves, or villains, or madmen, or 'smiths or other artificers, or oarsmen, boatswains, or the like.'"[1]:21–2

Plutarch's "Were the Athenians More Famous in War or in Wisdom?"

The Moralia of Plutarch contain an essay often given the title "Were the Athenians More Famous in War or in Wisdom?", which reflects many of the dissenting views of Plato. It is an example of epideictic oratory, and incomplete; since it is a rhetorical exercise, it is unsafe to assume that those views were Plutarch's own.[5] In any case, his main argument moves onto the idea of imitation as it affects society, rather than the individual actor. Plutarch wonders what it has to say about us that we take pleasure in watching an actor express strongly negative emotions on stage, where the opposite would be true in real life.[1]:34

Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity

Cicero writes that "dramatic art and the theatre is generally disgraceful" and this seems to be a majority opinion in the height of the Roman Empire.[1]:38 Permanent theater spaces were forbidden to be built, indicating a low priority for the theater in the official sense, and forms of performance shifted to popular entertainments.[1]:39

Histriones and mimes

Theater in Rome is largely led by professional actor managers leading groups of actors (or histriones) consisting of foreigners, freedmen, and slaves. As Romans viewed public service for money to be disgraceful, this group became a disenfranchised class "virtually stricken, so far as the law was concerned, from the book of life"[1]:40 and were forbidden to vote, appoint or serve as attorneys, forbidden to leave the profession, and required to pass their employment on to their children.[1]:42 Mimes, which included female performers, were heavily sexual in nature and often equated with prostitution. Attendance at mime performances "must have seemed to many Romans like visiting the stews—equally urgent, equally provocative of guilt, and hence equally in need of being scourged by a savage backlash of official disapproval."[1]:43

Tatian and Tertullian's De spectaculis

Both Taitian and Tertullian (c. 160 CE–200 CE) represent some of the earliest stirrings of Christian writings suspicious of the theater because of the pleasure it brings.[1]:44 In De spectaculis, Tertullian argues that even moderate pleasure is to be avoided and that theater, with its large crowds and deliberately exciting mimetic performances, leads to "mindless absorption in the imaginary fortunes of nonexistent characters."[1]:45 To Tertullian, acting is ever amassing system of falsifications, his own identity (a deadly sin), an impersonation of one who may be vicious (a further sin) "First the actor falsifies his identity, and so compounds a deadly sin. If he impersonates someone vicious, he further compounds the sin."[1]:46–7 And if modification is required, say a men representing a woman, it is a "lie against our own faces, and an impious attempt to improve the works of the Creator."[1]:49

St. John Chrysostom

"He who converses of theatres and actors does not benefit [his soul], but inflames it more, and renders it more careless... he who converses about hell incurs no dangers, and renders it more sober."[1]:51 To St. John Chrysostom it is the converse of pleasure that brings salvation.

St. Augustine's Confessions

The following passages are expressed in St. Augustine's Confessions. "I find in these examples nothing worthy of imitation. To the end that we may be true to our nature, we should not become false by copying and likening to the nature of another as do the actors and the reflections in the mirror ... We should, instead, seek that truth which is not self-contradictory and two-faced."[1]:57

"For in the theatre, dens of iniquity though they may be, if a man is fond of a particular actor, and enjoys his art as a great or even as the very greatest good, he is fond of all who join with him in admiration of his favorite, not for their own sakes, but for the sake of him whom they admire in common; and the more fervent he is in his admiration, the more he works in every way he can to secure new admirers for him, and the more anxious he becomes to show him to others; and if he find any one comparatively indifferent, he does all he can to excite his interest by urging his favorite's merits: if, however, he meet with any one who opposes him, he is exceedingly displeased by such a man's contempt of his favorite, and strives in every way he can to remove it. Now, if this be so, what does it become us to do who live in the fellowship of the love of God, the enjoyment of whom is the true happiness of life...?"[1]:58

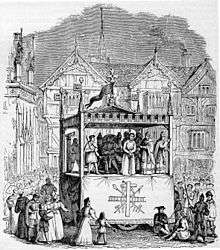

The Church and the Middle Ages

Theater in the Middle Ages took its subject matter from religion and seems to have been largely endorsed and only peripherally shunned.[1]:66–67

A treatise of miraclis pleyinge

This anonymous text from a fourteenth-century sermon, generally agreed to be of Lollard inspiration, while a minority opinion, is one of the few surviving examples of antitheatrical prejudice in the Middle Ages. It is not clear if the anonymous text is referring to the performance of mystery plays on the streets or liturgical drama in the church or possibly the author is making no distinction.[1]:76 Barish traces the meanings of the preacher's prejudice to "the lifelike immediacy of the theater, which puts it in unwelcome competition with the everyday realm and with the doctrines espoused in schools and churches."[1]:79

Due to a play's basic objective to please, the preacher finds the purpose to be suspect as Christ never laughed. If one laughs or cries at a play it is because of the "pathos of the story" and their expression of emotion is therefore useless in the eyes of God.[1]:68–9 To this preacher it is the playmaking itself that is to blame for their sinful nature. "It is the concerted, organized, professionalized nature of the enterprise that offends so deeply, the fact that it entails planning and teamwork and elaborate preparation, making it different from the kind of sin that is committed inadvertently, or in a fit of ungovernable passion."[1]:70

In Early Modern England

A return was seen to Plato's reasoning on mimesis, in the 16th century. In particular the boy player, who took on female roles, was an issue, in terms of the assumption of female clothing and gesture. Also taken as problematic was the representation of the high-born and rulers, by those of low birth.[6] Writers hostile to drama as performed could make an exception for closet dramas, especially those that were religious, and their content.[7] An established point among critics was that the objection was to live performance, rather than to the dramatic work or its writer.[8]

.jpg)

Clothing was an object of Ben Jonson's prejudice, lending itself to unpleasing mannerisms and an artificial triviality.[1]:151 His plays rejected the Elizabethan theatricality that often relied on special effects. These things, said Jonson, offended "nature and truth after its long bondage to false conventions."[1]:134–135 His own court masques were expensive, exclusive spectacles known as for which he was a primary writer.[9] He had his work collected for a folio printing in 1616, "a more lasting medium" than the stage.[1]:138

Barish identifies Jonson as belonging to the Christian-Platonic-Stoic tradition "that finds value embodied in what is immutable and unchanging, and tends to dismiss as unreal whatever is past and passing and to come."[1]:143 His plays feature characters who remain silent or static in the face of great obstacles, or present others foolish in their embracing of a changing world.[1]:144–5 He put typical anti-theatrical arguments into the mouth of his Puritan preacher Zeal of the Land Busy, in Bartholomew Fair. They included the Puritan view that men mimicking women was forbidden in the Bible, in Deuteronomy. The text states that "The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman's garment: for all that do so are an abomination unto the Lord thy God."[10][11]

Thomas Becon, an early evangelical Protestant reformer, wrote a letter The Displaying of the Popish Mass while a Marian exile.[12] It covers perceived problems for the Church involved in theatrical reenactments with any kind of embellishments. "By introducing ceremonial costume, ritual gesture, and symbolic decor, and by separating the clergy from the laity, the church has perverted a simple communal event into a portentous masquerade, a magic show designed to hoodwink the ignorant."[1]:161 Of a mass with too much pomp, a spectator plays a passive, entertained role in a production led by a kind of surrogate for the message of God.[1]:165

Prynne's Histriomastix, the Players Scourge, or Actors Tragedie

Published in 1633, William Prynne's Histriomastix is an encyclopedic tome, scourging many different types of theater in broad, repetitious, and fiery ways. The title page reads: "Histrio-mastix. The players scourge, or, actors tragædie, divided into two parts. Wherein it is largely evidenced, by divers arguments, by the concurring authorities and resolutions of sundry texts of Scripture, That popular stage-playes are sinfull, heathenish, lewde, ungodly spectacles, and most pernicious corruptions; condemned in all ages, as intolerable mischiefes to churches, to republickes, to the manners, mindes, and soules of men. And that the profession of play-poets, of stage-players; together with the penning, acting, and frequenting of stage-playes, are unlawfull, infamous and misbeseeming Christians. All pretences to the contrary are here likewise fully answered; and the unlawfulnes of acting, of beholding academicall enterludes, briefly discussed; besides sundry other particulars concerning dancing, dicing, health-drinking, &c. of which the table will informe you."[1]:83–4

Prynne's outstanding objection to the theater is that it encourages pleasure and recreation over work, and increases sexual desire with its excitement and effeminacy.[1]:85 While a particularly acute attack, Histromastix represents a common anti-theatrical view held by many, from around 1575 to the closure of the theaters in 1642.[1]:88

1642 theatre closure

A closure of the London theaters came in 1642, at the start of the First English Civil War.[1]:88

Seventeenth-century France

Like Puritanism in England, Jansenism is the moral adversary to the theater in France that has a similar tone of vitriol and absolutism. However, "the debate in France proceeds on an altogether more analytical, more intellectually responsible plane. The antagonists attend more carefully to the business of argument and the rules of logic; they indulge less in digression and anecdote."[1]:193

Jansenism

Jansenists denied the freedom of human will stating that "man can do nothing—could not so much as obey the ten commandments—without an express interposition of grace, and when grace came, its force was irresistible" and that pleasure is forbidden because it makes an addict of us.[1]:200–201 Pierre Nicole speaks on the moral objection not for concern for the makers of theater, the vice den of the theater space itself, or the disorder it is presumed to cause, but rather the content that he finds "intrinsically corrupting." By an actor drawing up such base actions as lust, hate, greed, vengeance, and despair he must draw upon something immoral in his own soul not worth dwelling on.[1]:194 Even with positive emotions, they are still lies performed by hypocrites. The concern is a psychological one, for by experiencing these things, the actor must stir up the emotions in himself and the audience. Christian thought viewed these heightened, temporal emotions as something needing to swelled and denied. Therefore, both the actor and audience should feel shameful for its collective participation.[1]:196

Francois de La Rochefoucauld's Reflexions diverses

Published in 1731, Francois de La Rochefoucauld writes of innate manners we are all born with and "when we copy others, we forsake what is authentic to us and sacrifice our own strong points for alien ones that may not suit us at all."[1]:217 By imitating others, including the good, all things are reduced to ideas and caricatures of themselves and even with the intent of betterment, it leads directly to confusion. Mimesis must, therefore, be abandoned entirely.[1]:219–20

Rousseau

.jpg)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau holds the primary belief that all men are created good and that it is society that attempts to corrupt. Luxurious things are primarily to blame for these moral corruptions and, as stated in his Discourse on the Arts, Discourse, On the Origins of Inequality and Letter to d'Alembert,[1]:257 the theater is central to this downfall. Rousseau argues for a nobler, simpler life free of the "perpetual charade of illusion, created by self-interest and self-love."[1]:258

Furthermore, Rousseau dismisses any relevance of great classical works, denouncing Sophocles by saying the plays have no relevance over us and that they affects us much less than we have previously believed.[1]:264–5 Instead of looking at our lives as they exist, we look to others in order to "transport ourselves beyond ourselves"[1]:263 and that is corrupting our inherent goodness provided at birth.

The use of women in theater is disturbing for Rosseau as they especially are designed by nature for modest roles not becoming of an actress.[1]:282 "The new society is not in fact too be encouraged to evolve its own morality but to revert to an earlier one, to the paradisal time when men were hardy and virtuous, women housebound and obedient, young girls chaste and innocent. In such a reversion, the theater—with all it symbolizes of the hatefulness of society, its hypocrisies, its rancid politeness, its heartless masqueradings—has no place at all."[1]:294

Eighteenth century

Early America

In 1778, just two years after declaring the United States as a nation, a law was passed to abolish theater, gambling, horse racing, and cockfighting—all on the grounds of their sinful nature. This pushes theatrical practices into American universities where it is also met with hostility, particularly from that of Timothy Dwight IV of Yale University and John Witherspoon of Princeton College.[1]:296 The latter, with his work Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Stage outlines similar arguments to his predecessors with the addition of the accusation that theater is too truthful to life and is therefore considered an improper method of instruction. "Now are not the great majority of characters in real life bad? Must not the greatest part of those represented on the stage be bad? And therefore, must not the strong impression which they make upon the spectators be hurtful in the same proportion?"[1]:297 he writes.

William Wilberforce

From A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians... Contrasted with Real Christianity (1797): "For Wilberforce the theater is a place haunted by debauchees bent on gratifying their appetites, from which modesty and regularity have retreated, 'while riots and lewdness' are invited to the spot' where God's name is profaned, and the only lessons to be learned are those Christians should shun like the pains of hell."[1]:303

Nineteenth century

"From our present point of vantage in time, nineteenth-century attacks on theater frequently have the air of a psychomachia: the artistic conscience, struggling against the grossness of the physical stage, striving to free itself from the despotism of the actors, resembles the spirit warring against the flesh, the soul wrestling with the body, or the virtues launching their assault on the vices. But the persistence of the struggle seems to suggest that it is more than a temporary skirmish: it reflects an abiding tension in our natures as social beings."[1]:349

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen (1814)

An odd source for anti-theatricalism can been seen in Jane Austen's Mansfield Park with the disapproval of Sir Thomas Bertram for his children's amateur play productions that he vehemently argues against with statements such as "unsafe amusements" and "noisy pleasures" that will "offend his ideas of decorum."[1]:300–301

Becky Sharp in William Makepeace Thackeray's Vanity Fair

In Vanity Fair, Sharp, an exceptionally gifted ingenue for her skills with mimicry is looked upon with much suspicion. Her talents lend themselves to "a calculated deceptiveness" and "systematic concealment of her true intentions" that is unbecoming of any British woman.[1]:307–310

Encyclopedie théologique (1847)

"The excommunication pronounced against comedians, actors, actresses tragic or comic, is of the greatest and most respectable antiquity... it forms part of the general discipline of the French Church... This Church allows them neither the sacraments nor burial; it refuses them its suffrages and its prayers, not only as infamous persons and public sinners, but as excommunicated persons... One must deal with the comedians as with public sinners, remove them from participation with holy things while they belong to the theater, admit when they leave it."[1]:321

Auguste Comte and positivism

Utopian writer Comte does not allow the theater in his idealist society. It is a "concession to our weakness, a symptom of our irrationality, a kind of placebo of the spirit with which the good society will be able to dispense"[1]:323 and also a kind of spilt religion, "something to be replaced by a rational apparatus of public worship."[1]:324

Romanticism closet drama, and Charles Lamb

Romanticism veers from the course of thought set by Plato that plays are about action preferring instead to look inward for an "absolute sincerity which speaks directly from the soul, a pure expressiveness that knows nothing of the presence of others."[1]:326 For writers such as Charles Lamb, this leads to verbose claims that even writers as theater-worthy as Shakespeare have no place onstage, for the fault of the theater is a focus on the surface of things that crushes the delicacy of the written word in favor of "harsh lights, violent gestures, and braying voices."[1]:328–9 In his essay "On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, Considered with Reference to Their Fitness for Stage Representation", he states that "all those delicacies which are so delightful in the reading...are sullied and turned from their very nature."[13]

This kind of thinking contributes to the creation of closet drama that can be seen as "a refusal to bow to the realities of theaters and actors, in the name of a freedom which is self-pampering and illusory."[1]:336

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 Barish, Jonas (1981). The Antitheatrical Prejudice. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0520052161.

- 1 2 Fischer, Eileen (1982). "[Review of The Antitheatrical Prejudice by Jonas Barish]". Modern Drama. 25 (3).

- ↑ Martin Puchner (1 April 2003). Stage Fright: Modernism, Anti-Theatricality, and Drama. JHU Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8018-7776-6.

- ↑ Jean Kinney Williams (1 January 2009). Empire of Ancient Greece. Infobase Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4381-0315-0.

- ↑ David Edward Aune (2003). The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-664-21917-8.

- ↑ Mark Thornton Burnett; Adrian Streete; Ramona Wray (31 October 2011). The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts. Edinburgh University Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-7486-3524-5.

- ↑ Marta Straznicky (25 November 2004). Privacy, Playreading, and Women's Closet Drama, 1550-1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-84124-5.

- ↑ Michael O'Connell (13 January 2000). The Idolatrous Eye: Iconoclasm and Theater in Early-Modern England. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-534402-8.

- ↑ Brocket, Oscar G. (2007). History of the Theatre: Foundation Edition. Boston, New York, San Francisco: Pearson Education. p. 128. ISBN 0-205-47360-1.

- ↑ Jane Milling; Peter Thomson (23 November 2004). The Cambridge History of British Theatre. Cambridge University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-521-65040-3.

- ↑ Barish, Jonas (1966). "The Antitheatrical Prejudice". Critical Quarterly. 8: 340.

- ↑ Thomas Becon (1843). The Early Works of Thomas Becon: Being the Treatises Published by Him in the Reign of King Henry VIII. University Press. p. xii.

- ↑ Lamb, Charles. "On the Tragedies of Shakspere Considered with Reference to Their Fitness for Stage Representation".

Further reading

- Davidson, C. (January 1997). "The Medieval Stage and the Antitheatrical Prejudice". Parergon. 14 (2): 1–14. doi:10.1353/pgn.1997.0019.

- Dennis, N. (March 2008). "The Illegitimate Theater. [Review of Against Theatre: Creative Destructions on the Modernist Stage]". Theatre Journal. 60 (1): 168–9.

- Hawkes, D. (1999). "Idolatry and Commodity Fetishism in the Antitheatrical Controversy". SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900. 39 (2): 255–73. doi:10.1353/sel.1999.0016.

- Stern, R. F. (1998). "Moving Parts and Speaking Parts: Situating Victorian Antitheatricality". ELH. Vol. 65 (2): 423–49. doi:10.1353/elh.1998.0016.

- Williams, K. (Fall 2001). "Anti-theatricality and the Limits of Naturalism". Modern Drama. 44 (3): 284–99. doi:10.3138/md.44.3.284.