Annibale Carracci

| Annibale Carracci | |

|---|---|

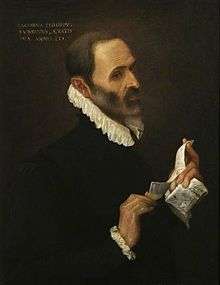

Self-portrait (Uffizi) | |

| Born |

November 3, 1560 Bologna |

| Died |

July 15, 1609 (aged 48) Rome |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Baroque |

Annibale Carracci (Italian pronunciation: [anˈnibale karˈrattʃi]; November 3, 1560 – July 15, 1609) was an Italian painter, active in Bologna and later in Rome. Along with his brothers, Annibale was one of the progenitors, if not founders of a leading strand of the Baroque style, borrowing from styles from both north and south of their native city, and aspiring for a return to classical monumentality, but adding a more vital dynamism. Painters working under Annibale at the gallery of the Palazzo Farnese would be highly influential in Roman painting for decades.

Early career

Annibale Carracci was born in Bologna, and in all likelihood was first apprenticed within his family. In 1582, Annibale, his brother Agostino and his cousin Ludovico Carracci opened a painters' studio, initially called by some the Academy of the Desiderosi (desirous of fame and learning) and subsequently the Incamminati (progressives; literally "of those opening a new way"). While the Carraccis laid emphasis on the typically Florentine linear draftsmanship, as exemplified by Raphael and Andrea del Sarto, their interest in the glimmering colours and mistier edges of objects derived from the Venetian painters, notably the works of Venetian oil painter Titian, which Annibale and Agostino studied during their travels around Italy in 1580–81 at the behest of the elder Caracci Lodovico. This eclecticism was to become the defining trait of the artists of the Baroque Emilian or Bolognese School.

In many early Bolognese works by the Carraccis, it is difficult to distinguish the individual contributions made by each. For example, the frescoes on the story of Jason for Palazzo Fava in Bologna (c. 1583–84) are signed Carracci, which suggests that they all contributed. In 1585, Annibale completed an altarpiece of the Baptism of Christ for the church of Santi Gregorio e Siro in Bologna. In 1587, he painted the Assumption for the church of San Rocco in Reggio Emilia.

In 1587–88, Annibale is known to have had travelled to Parma and then Venice, where he joined his brother Agostino. From 1589 to 1592, the three Carracci brothers completed the frescoes on the Founding of Rome for Palazzo Magnani in Bologna. By 1593, Annibale had completed an altarpiece, Virgin on the throne with St John and St Catherine, in collaboration with Lucio Massari. His Resurrection of Christ also dates from 1593. In 1592, he painted an Assumption for the Bonasoni chapel in San Francesco. During 1593-94, all three Carraccis were working on frescoes in Palazzo Sampieri in Bologna.

Frescoes in Palazzo Farnese

Based on the prolific and masterful frescoes by the Carracci in Bologna, Annibale was recommended by the Duke of Parma, Ranuccio I Farnese, to his brother, the Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, who wished to decorate the piano nobile of the cavernous Roman Palazzo Farnese. In November–December 1595, Annibale and Agostino traveled to Rome to begin decorating the Camerino with stories of Hercules, appropriate since the room housed the famous Greco-Roman antique sculpture of the hypermuscular Farnese Hercules.

Annibale meanwhile developed hundreds of preparatory sketches for the major work, wherein he led a team painting frescoes on the ceiling of the grand salon with the secular quadri riportati of The Loves of the Gods, or as the biographer Giovanni Bellori described it, Human Love governed by Celestial Love. Although the ceiling is riotously rich in illusionistic elements, the narratives are framed in the restrained classicism of High Renaissance decoration, drawing inspiration from, yet more immediate and intimate, than Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling as well as Raphael's Vatican Logge and Villa Farnesina frescoes. His work would later inspire the untrammelled stream of Baroque illusionism and energy that would emerge in the grand frescoes of Cortona, Lanfranco, and in later decades Andrea Pozzo and Gaulli.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the Farnese Ceiling was considered the unrivaled masterpiece of fresco painting for its age. They were not only seen as a pattern book of heroic figure design, but also as a model of technical procedure; Annibale’s hundreds of preparatory drawings for the ceiling became a fundamental step in composing any ambitious history painting.

Contrast with Caravaggio

The 17th-century critic Giovanni Bellori, in his survey entitled Idea, praised Carracci as the paragon of Italian painters, who had fostered a “renaissance” of the great tradition of Raphael and Michelangelo. On the other hand, while admitting Caravaggio's talents as a painter, Bellori deplored his over-naturalistic style, if not his turbulent morals and persona. He thus viewed the Caravaggisti styles with the same gloomy dismay. Painters were urged to depict the Platonic ideal of beauty, not Roman street-walkers. Yet Carracci and Caravaggio patrons and pupils did not all fall into irreconcilable camps. Contemporary patrons, such as Marquess Vincenzo Giustiniani, found both applied showed excellence in maniera and modeling.[1]

In our century, observers have warmed to the rebel myth of Caravaggio, and often ignore the profound influence on art that Carracci had. Caravaggio almost never worked in fresco, regarded as the test of a great painter's mettle. On the other hand, Carracci's best works are in fresco. Thus the somber canvases of Caravaggio, with benighted backgrounds, are suited to the contemplative altars, and not to well-lit walls or ceilings such as this one in the Farnese. Wittkower was surprised that a Farnese cardinal surrounded himself with frescoes of libidinous themes, indicative of a "considerable relaxation of counter-reformatory morality". This thematic choice suggests Carracci may have been more rebellious relative to the often-solemn religious passion of Caravaggio's canvases. Wittkower states Carracci's "frescoes convey the impression of a tremendous joie de vivre, a new blossoming of vitality and of an energy long repressed".

Today, unfortunately, most connoisseurs making the pilgrimage to the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo would ignore Carracci’s Assumption of the Virgin altarpiece (1600–1601) and focus on the stunning flanking Caravaggio works. It is instructive to compare Carracci's Assumption[2] with Caravaggio's Death of the Virgin. Among early contemporaries, Carracci would have been an innovator. He re-enlivened Michelangelo's visual fresco vocabulary, and posited a muscular and vivaciously brilliant pictorial landscape, which had been becoming progressively crippled into a Mannerist tangle. While Michelangelo could bend and contort the body into all the possible perspectives, Carracci in the Farnese frescoes had shown how it could dance. The "ceiling"-frontiers, the wide expanses of walls to be frescoed would, for the next decades, be thronged by the monumental brilliance of the Carracci followers, and not Caravaggio's followers.

In the following century, it was not the admirers of Caravaggio who would have dismissed Carracci, but to a lesser extent than Bernini and Cortona, baroque art in general came under criticism from neoclassic critics such as Winckelmann and even later from the prudish John Ruskin. Carracci in part was spared opprobrium because he was seen as an emulator of the highly admired Raphael, and in the Farnese frescoes, attentive to the proper themes such as those of antique mythology.

Landscapes, genre art and drawings

On July 8, 1595, Annibale completed the painting of San Rocco distributing alms, now in Dresden Gemäldegalerie. Other significant late works painted by Carracci in Rome include Domine, Quo Vadis? (c. 1602), which reveals a striking economy in figure composition and a force and precision of gesture that influenced on Poussin and through him, the language of gesture in painting.

Carracci was remarkably eclectic in thematic, painting landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits, including a series of autoportraits across the ages. He was one of the first Italian painters to paint a canvas wherein landscape took priority over figures, such as his masterful The Flight into Egypt; this is a genre in which he was followed by Domenichino (his favorite pupil) and Claude Lorrain.

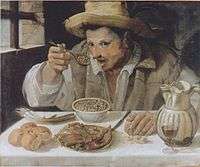

Carracci's art also had a less formal side that comes out in his caricatures (he is generally credited with inventing the form) and in his early genre paintings, which are remarkable for their lively observation and free handling[3] and his painting of The Beaneater. He is described by biographers as inattentive to dress, obsessed with work: his self-portraits vary in his depiction.[4]

Under a melancholic humor

It is not clear how much work Annibale completed after finishing the major gallery in the Palazzo Farnese. In 1606, Annibale signs a Madonna of the bowl. However, in a letter from April 1606, Cardinal Odoardo Farnese bemoans that a "heavy melancholic humor" prevented Annibale from painting for him. Throughout 1607, Annibale is unable to complete a commission for the Duke of Modena of a Nativity. There is a note from 1608, where in Annibale stipulates to a pupil that he will spend at least two hours a day in his studio.

There is little documentation from the man or time to explain why his brush was stilled. Speculation abounds.

In 1609, Annibale died and was buried, according to his wish, near Raphael in the Pantheon of Rome. It is a measure of his achievement that artists as diverse as Bernini, Poussin, and Rubens praised his work. Many of his assistants or pupils in projects at the Palazzo Farnese and Herrera Chapel would become among the pre-eminent artists of the next decades, including Domenichino, Francesco Albani, Giovanni Lanfranco, Domenico Viola, Guido Reni, Sisto Badalocchio, and others.

Chronology of works

- Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1590)—Oil on canvas, 130 × 97 cm, Museo del Prado

- The Baptism of Christ (1584)—Oil on canvas, San Gregorio, Bologna

- The Beaneater (1580–1590)—Oil on canvas, 57 × 68 cm, Galleria Colonna, Rome

- Butcher's Shop (1580s)—Oil on canvas, 185 × 266 cm, Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford

- Crucifixion (1583)—Oil on canvas, 305 × 210 cm, Santa Maria della Carità, Bologna

- Corpse of Christ (c. 1583-1585)—Oil on canvas, 70.7 × 88.8 cm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

- Descent From the Cross (1580–1600) St. Ann's, Manchester

- Fishing (before 1595)—Oil on canvas, 136 × 253 cm, Musée du Louvre

- Hunting (before 1595)—Oil on canvas, 136 × 253 cm, Musée du Louvre

- The Laughing Youth (1583)—Oil on paper, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Madonna Enthroned with St Matthew (1588)—Oil on canvas, 384 × 255 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine (1585–1587)—Oil on canvas, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

- Venus, Adonis and Cupid (c. 1595)—Oil on canvas, 212 × 268 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- "Jupiter and Juno" (c. 1597)—Farnese Gallery, Rome[5]

- River Landscape (c. 1599)—Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[6]

- Venus and Adonis (c. 1595)—Oil on canvas, 217 × 246 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Venus with a Satyr and Cupids (c. 1588)—Oil on canvas, 112 × 142 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- The Virgin Appears to the Saints Luke and Catherine (1592)—Oil on canvas, 401 × 226 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Frescoes (1597–1605) in the Palazzo Farnese, Rome

- Assumption of the Virgin Mary (1600–1601)—Oil on canvas, 245 × 155 cm, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

- Lamentation of Christ (1606)—Oil on canvas, 92.8 × 103.2 cm, National Gallery, London

- Sleeping Venus (c. 1603)—Oil on canvas, 190 × 328 cm, Musée Condé, Chantilly, Oise

- The Flight into Egypt (1603)—Oil on canvas, 122 × 230 cm, Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

- The Choice of Heracles (c. 1596)—Oil on canvas, 167 × 273 cm, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

- Mocking of Christ (c. 1596)—Oil on canvas, 60 × 69.5 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionale

- Pietà (1599–1600)—Oil on canvas, 156 × 149 cm, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

- Domine quo vadis? (1601–1602)—Oil on panel, 77.4 × 56.3 cm, National Gallery, London

- Rest on Flight into Egypt (c. 1600)—Oil on canvas, diameter 82.5 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Self-Portrait in Profile (1590s)—Oil on canvas, Uffizi, Florence

- Self-portrait (c. 1604)—Oil on wood, 42 × 30 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- The Martyrdom of St Stephen (1603–1604)—Oil on canvas, 51 × 68 cm, Louvre, Paris

- Triptych (1604–1605)—Oil on copper and panel, 37 × 24 cm (central panel), 37 × 12 cm (each wing), Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome

- Holy Women at the Tomb of Christ Oil on canvas, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Atlante Sanguine, Louvre, Paris

- Drawings (exhibit, National Gallery of Art)[7]

Paintings

The tradition of Italian Renaissance painting and the mature Renaissance artists like Raphael, Michelangelo, Correggio, Titian and Veronese are all painters who had a considerable influence on the work of the Carracci, in his use of colours. Carrci laid the foundations for the birth of Baroque painting. The preceding sterile Mannerist style had its recovery now in the Baroque painting in the early sixteenth century, succeeding in an original synthesis of the many schools. The paintings of Annibale are inspired by the Venetian pictorial taste and especially the paintings of Paolo Veronese. The work that show traces of it are the Madonna Enthroned with Saint Matthew, a work made for Reggio Emilia and now in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden, and the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (ca. 1575), now preserved at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice.[8][9]

- Religious subjects

-

Christ Wearing the Crown of Thorns, Supported by Angels

-

The Samaritan Woman at the Well

-

The silent Madonna with Saint John the Baptist

-

Susanna in the bath

-

Pietà, Kunsthistoriche Museum, Vienna

-

Lamentation of Christ

-

Madonna and Child with St John

-

Saint Roch and the Angel

- Portraits

-

Self-portrait c. 1580

-

_-_WGA4426.jpg)

The Temptation of St Anthony Abbot (detail) 1597 and 1598

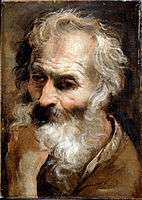

-

Head of an Old Man

-

Portrait of Dr Bossi.

- Mythological subjects

-

Venus and Adonis circa 1595

-

Landscape with the Toilet of Venus

-

The Judgment of Hercules, 1596, National Museum of Capodimonte

-

Venus with a Satyr and Cupids, 1590

- Food related paintings

-

Boy Drinking by Annibale Carracci, 1582–83

-

The Beaneater, 1580-1590, Galleria Colonna, Rome

Footnotes

- ↑ Wittkover, p. 57.

- ↑ See the more adept altarpiece at the Prado (Paintings by Annibale Carracci. Web Gallery of Art, retrieved May 28, 2011)

- ↑ see The Butcher's Shop

- ↑ see mostra (Italian)

- ↑ File:Jupiter and Juno - Annibale Carracci - 1597 - Farnese Gallery, Rome.jpg

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-11-11. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- ↑ "Annibale Carracci, Images - NGA". nga.gov.

- ↑ "Annibale Carracci". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved October 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "carracci/annibale". www.wga.hu. Retrieved October 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

References

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Carracci

- Christiansen, Keith. “Annibale Carracci (1560–1609).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2003)

- Wittkower, Rudolph (1993). "Art and Architecture Italy, 1600-1750". Pelican History of Art. 1980. Penguin Books. pp. 57–71.

- Gianfranco, Malafarina (1976). "preface by Patrick J. Cooney". L' opera completa di Annibale Carracci,. Rizzoli Editore, Milano.

- H. Keazor: Distruggere la maniera?": die Carracci (Postille:Freiburg im Breisgau), 2002.

- C. Dempsey: Annibale Carracci and the beginnings of baroque style, Harvard, 1977; 2nd ed. Fiesole, 2000.

- A. W. A. Boschloo: Annibale Carracci in Bologna: visible reality in art after the Council of Trent, 's-Gravenhage, 1974.

- C. Goldstein: Visual fact over verbal fiction: a study of the Carracci and the criticism, theory, and practice of art in Renaissance and baroque Italy, Cambridge, 1988.

- D. Posner: Annibale Carracci: a study in the reform of Italian painting around 1590, 2 vol., New York, 1971.

- S. Ginzburg: Annibale Carracci a Roma: gli affreschi di Palazzo Farnese, Rome, 2000.

- C. Loisel: Inventaire général des dessins italiens, vol. 7: Ludovico, Agostino, Annibale Carracci (Musée du Louvre: Cabinet des Dessins), Paris, 2004.

- B. Bohn: Ludovico Carracci and the art of drawing, London, 2004.

- Annibale Carracci, catalogo della mostra a cura di D. Benati, E. Riccomini, Bologna-Roma, 2006-2007.

- M. C. Terzaghi: Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni tra le ricevute del Banco Herrera & Costa, Roma, 2007.

- Henry Keazor: "Il vero modo". Die Malereireform der Carracci", Neue Frankfurter Forschungen zur Kunst, 5, Berlin: Mann Verlag, 2007:343.

- C. Robertson: The Invention of Annibale Carracci (Studi della Bibliotheca Hertziana, 4), Milano, 2008.

- Henry Keazor, Henry (2007). Il vero modo. Die Malereireform der Carracci. 2007. Gebrueder Mann Verlag.

- F. Gage: "Invention, Wit and Melancholy in the Art of Annibale Carracci." Intellectual History Review 24.3 (2014): 389-413. Special Issue, The Nature of Invention. Edited by Alexander Marr and Vera Keller.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Annibale Carracci. |

- Annibale Carracci artistic context, technique and artworks

- Annibale Carracci at the WikiGallery.org

- Annibale Carracci, Christ Healing the Sick, 16th century, etching, Bryn Mawr College Art and Artifact Collections

- Jusepe de Ribera, 1591-1652, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Carracci (see index)

- Painters of reality: the legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Carracci (see index)