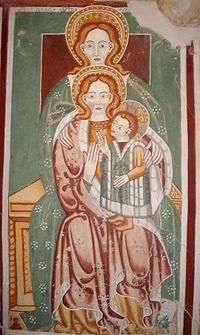

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

.jpg)

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne[1][2] or Madonna and Child with Saint Anne[3][4] is a subject in Christian art showing Saint Anne with her daughter, the Virgin Mary, and her grandson Jesus.[5] This depiction has been popular in Germany and neighboring countries since the 14th century.

Names

Names for this particular subject in other languages include:

- Dutch: Anna te Drieën[6]

- French: Anne Trinitaire[7]

- German: Anna Selbdritt[8]

- Italian: Anna Metterza[1][7]

- Slovene: Ana Samotretja[9]

Mother and daughter

The relationship of St. Anne to the immaculate conception of her daughter is not explicit, but her mystical participation is implied in the nested framing of her embrace of her virgin daughter embracing her divine grandson. This should not be confused with the perpetual virginity of Mary or the virgin birth of Jesus. Although the belief was widely held since at least Late Antiquity, the doctrine was not formally proclaimed until December 8, 1854 when it was dogmatically defined in the Western Latin Rite by Pope Pius IX via his papal bull, Ineffabilis Deus. It was never explicitly so in the Eastern churches; see discussion on dogma below.

Similar works featuring mother and daughter resemble that of the Throne of Wisdom, a pairing of mother and daughter known as the Education of the Virgin. The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne is distinct from the triangular composition featuring the infant Jesus yet relates the same mystery: an open book represents the immanence of Logos or Incarnate Word at all times in time and space, even before his Nativity. A trinitarian action of grace is implied: creator Father, redeemer Son, reflexive procession of the Holy Spirit (indicated by the vertically-tiered arrangement with Christ pointing back at his mother and grandmother.

Dogma in word and image

In the 13th century the general opinion was that the title "Immaculate Conception" was appropriately deferential to the Mother of God, but it could not be seen how to resolve the problem that only with Christ's death would the stain of original sin be removed. The great philosophers and theologians of the West were divided on the subject: the Dominican St. Thomas Aquinas siding with those who declined to defend the doctrine definitively and Blessed Duns Scotus attacked for his novel philosophical definition founded in Christological theology. Five hundred years later, this teaching was proclaimed by Pope Pius IX in 1854.

The creedal statement "and (from) the Son" adopted in the Christian West expresses a threefold mystery of Divine action: preserving his mother from the effects of sin through the merits of self-emptying obedience of the son to his Father at his passion and death. Grace perfects nature. Eastern Orthodox creedal expressions are not explicit on the mutual participation of the three persons of the Holy Trinity. The mystery of Mary's immaculate conception was also implied in depictions of her parents' chaste embrace meeting at the Golden Gate, the threshold of the Holy city of Jerusalem, a convention that symbolizes close proximity to (and participation with) the celestial Kingdom. In Jewish tradition, the Golden Gate this is that through which the Messiah will enter Jerusalem. Duns Scotus also taught the universal primacy of Christ as applied to the redemption of all souls not just that of Mary, the underlying rationale for the feast of Christ the King instituted in 1925.

Byzantine iconography

Eastern depictions of the apocryphal narrative mimic the scriptural account of the annunciation of the Angel Gabriel to Mary and take the form of a reclining Agios Joachim beside a double-vesicled fountain or well,[10] implying Mary's perpetual virginity flows from the mystery of her Immaculate Conception in the womb of her mother Agia Anna in linear fashion conform with Eastern creedal statements on the procession of the Holy Spirit. Absent modern meteorology, and therefore the scientific knowledge of how surface water is replenished naturally by atmospheric moisture, the early Christian artist was limited by linear symbolism of gravity known in the topography of the region.[11] Dewfall and the phenomenon of manna in the desert would have been known but revered as ineffable.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Madonna and Child with Saint Anne. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holy Kinship. |

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (Leonardo da Vinci)

- Virgin and Child with St. Anne (Masaccio)

- Metterza

- Holy Kinship

- Coat of arms of Annaberg-Bucholz, in the Saxony's Erzgebirge ("Ore Mountains") a mountain range which forms part of border between Germany and the Czech Republic

References

- 1 2 Tinagli, Paola. 1997. Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation and Identity. Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 159.

- ↑ Kahsnitz, Rainer. 2005. Carved Splendor: Late Gothic Altarpieces in Southern Germany, Austria and South Tyrol. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, p. 442.

- ↑ Rowlands, Eliot Wooldridge. 2003. Masaccio: Saint Andrew and the Pisa Altarpiece. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, p. 22.

- ↑ Feigenbaum, Gail, & Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, eds. 2011. Sacred Possessions: Collecting Italian Religious Art, 1500–1900. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, p. 40.

- ↑ Sources of Christian Iconography incl. Protevangelium of James. the Golden Legend (131) and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew

- ↑ Dresen-Coenders, Lène et al. 1987. Saints and She-Devils: Images of Women in the 15th and 16th Centuries. London: Rubicon Press, p. 87.

- 1 2 Murray, Peter et al. 2013. The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 21.

- ↑ Crăciun, Maria, & Elaine Fulton. 2011. Communities of Devotion: Religious Orders and Society in East Central Europe, 1450–1800. Farnham, UK: Ashgate, p. 50.

- ↑ Jaki, Barbara. 2004. National Gallery of Slovenia: Guide to the Permanent Collection: Painting and Sculpture in Slovenia from 13th to the 20th Century. Ljubljana: National Gallery of Slovenia, p. 9.

- ↑ 11th-century mosaic Daphni monastery Greece depicting annunciation to Anna and Joachim)

- ↑ Patristic prefigurement - notes on ancient watercourses in the Holy Land