André Tiraqueau

André Tiraqueau (Latin: Andreas Tiraquellus) (1488–1558) was a French jurist and politician. He is known also as a patron of François Rabelais, and the character Trinquamelle in Gargantua and Pantagruel is traditionally identified with Tiraqueau.[1][2]

Life

He was a legal humanist based in Fontenay-le-Comte, Poitou, where he knew Amaury Bouchard.[3] He married Marie Cailler, daughter of Artus Caillier, a legal officer at Fontenay; the marriage took place in 1512, when she was still very young, and he proceeded with two works on the Querelle des femmes and married life.[4][5]

Tiraqueau held the local legal offices of juge-châtelain and lieutenant. He was appointed a counsellor of the Parlement of Paris in 1531.[6]

Works

Tiraqueau had a reputation as a prolific writer.

- De legibus connubialibus (1513). This work justifies the legal disabilities of women by appeal to jus gentium and divine law.[7] It began as part of a commentary on the customs of Poitou, and grew through numerous editions.[8]

- De nobilitate et jure primigeniorum (1549).[9] This work addressed the topic of nobility as social status and recognition, picking up from Bartolus who wrote a work with the same title. Tiraqueau's theory followed that of Bartolus, on the political and legal origins of nobility, as opposed to kinship; and integrated it with the French situation and the scientia juris.[10] The theory was undermined in the longer term by the French kings' use of venal office.[11]

He wrote a commentary on the Geniales dies of Alessandro Alessandri.[12]

Tiraqueau's works were collected, firstly in five volumes (1574), and then in seven (Frankfurt, from 1597). The arrangement in the seven-volume edition is:

- I: On nobility and primogeniture;

- II: legal rights in marriage;

- III: law of repossession;

- IV: Cessante causa;

- V: Legacies for pious use, and other works;

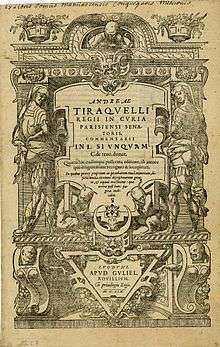

- VI: Commentary on Si unquam;

- VII: moderation of punishments.[13]

Friendship with Rabelais

Rabelais met Tiraqueau during his time as an Observantine Franciscan at Fontenay; he participated in the humanist circle there, in the early 1520s.[14] Tiraqueau was the dedicatee of an edition by Rabelais of the letters of Giovanni Manardi.[15]

As Rabelais was writing his Tiers Livre, Tiraqueau was collecting authorities for his work on nobility (1549). It has been suggested that Rabelais took largely from Tiraqueau's references.[2] Tiraqueau apparently cooled towards Rabelais in later life, and played down his public disagreement with Amaury Bouchard over women (of which Rabelais made much literary use).[16]

Notes

- ↑ Elizabeth A. Chesney, The Rabelais Encyclopedia (2004), p. 247; Google Books.

- 1 2 Edwin M. Duval, The Design of Rabelais's Tiers livre de Pantagruel, p. 136; Google Books.

- ↑ Screech, p. 17.

- ↑ Plattard, pp. 25–6; Google Books.

- ↑ (French) Etudes rabelaisiennes, Volume 43 (2006), p. 198; Google Books.

- ↑ Joan Thirsk, The Rural Economy of England: collected essays (1984), p. 362; Google Books.

- ↑ Constance Jordan, Renaissance Feminism: literary texts and political models (1990), p. 191; Google Books.

- ↑ Leigh Ann Whaley, Women's History as Scientists: a guide to the debates (2003), p. 51; Google Books.

- ↑ Oxford Companion to French Literature, at answers.com.

- ↑ Matthew P. Romaniello, Charles Lipp, Contested Spaces of Nobility in Early Modern Europe (2011), p. 151; Google Books.

- ↑ John Hearsey McMillan Salmon, Society in Crisis: France in the sixteenth century (1979), p. 112; Google Books.

- ↑ Chalmers biography of Alessandri.

- ↑ Frederick William Halfpenny, Catalogue of books on foreign law: founded on the collection presented by Charles Purton Cooper, esq., to the Society of Lincoln's Inn. Laws and jurisprudence of France. [Ancient part] (1849), pp. 132–3; Google Books.

- ↑ John O'Brien (editor), The Cambridge Companion to Rabelais (2011), p. 15; Google Books.

- ↑ Screech, p. 21.

- ↑ Plattard, p. 249; Google Books.

References

- Jean Plattard (1968), The Life of François Rabelais

- M. A. Screech (1979), Rabelais