Automotive Building

| Automotive Building, Allstream Centre | |

|---|---|

|

Main Entrance, 1929 | |

| Former names | Automotive Building |

| General information | |

| Type | Exhibition building |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| Location | Exhibition Place |

| Address | 105 Princes' Blvd |

| Coordinates | 43°38′02″N 79°24′38″W / 43.63381°N 79.41057°W |

| Groundbreaking | April 1929 |

| Construction started | April 1929 |

| Opened | August 26, 1929 |

| Cost | $1,000,299.26 |

| Renovation cost | $47,000,000 |

| Owner | Canadian National Exhibition |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Steel Truss |

| Floor count | 1 and mezzanine |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | D. E. Kertland |

| Main contractor | Jackson, Lewis Company[1] |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect | David Clusaiu, Principal architect |

| Renovating firm | NORR Limited, Architects & Engineers |

The Automotive Building, which houses the Allstream Centre, is a heritage building at Exhibition Place in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, containing event and conference space. As a result of burgeoning interest in automobiles, additional exhibition space for automotive exhibits during the annual Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) was needed. A design competition was held, the winning design submitted by Toronto architect Douglas Kertland. The building opened in 1929 and the "National Motor Show" exhibit of automobiles was held in the building until 1967. It was also used for trade shows. When it opened, it was claimed to be "the largest structure in North America designed exclusively to display passenger vehicles".[2]

After the ending of automotive exhibits at the CNE, the building was used for other CNE exhibits and continued to be used for trade shows. In the 2000s, the City of Toronto decided to turn over management of the building to a private company which renovated the building, building a ballroom in the main exhibit hall and conference rooms on the mezzanine level. The ballroom is considered the largest in Toronto. No longer used by the CNE or trade shows, the building is used year-round for various public and private events and conferences.

Description

The Automotive Building was constructed in 1929, designed by local architect Douglas Kertland in the Art Deco style. It is a two-storey building, 160,000 square feet (15,000 m2) in size.[3] The internal plan is a large open space with a mezzanine on the second floor surrounding the main floor.

The structure's base is stone from a quarry near Queenston Heights, Ontario with "artificial stone" up top. Sticking to all Canadian material and workmanship added to the cost: using Indiana stone would have cost $989,299.[1] The architect and general contractors noted that, while Queenston stone could be used throughout for an additional cost of $35,000, it would take too long for the shops to prepare the stone.[4] The tender required the winner to pay "a minimum of 50 cents an hour for all men employed on the building."[1]

It now houses the Allstream Centre conference centre and is connected underground to the underground parking garage of the Enercare Centre.[5] The open floor was converted to a 43,900 square feet (4,080 m2) ballroom, claimed to be largest in Toronto, which can be sub-divided in two.[6] The original glass roof over the open floor was replaced with a new ceiling. The second floor mezzanine saw the addition of 20 meeting rooms.[7]

Construction

Motor cars were first exhibited at the Canadian National Exhibition in 1897. In 1902, the CNE built the Transportation Building, where cars were displayed alongside streetcars, railway exhibits and carriages. Early automobiles on display included models from Autocar, Packard, Peerless, Stevens-Duryea and Thomas. The building was destroyed by fire and was replaced with a new building in 1909. By 1911, there were no longer any horse-drawn vehicles on display. The display was named the National Motor Show in 1916.[8]

As of 1928, the vehicles (including coupes, trucks, limousines, and buses) at the National Motor Show[9] were overflowing into the Coliseum "and other places,"[10] including the Electrical Building.[9] Visitors to the fair were noted to be increasingly coming by car, suggesting that every "state in the union is likely to be represented in the array of motor car markers on the grounds," and that it was "no new thing to see British Columbia and Alberta markers on the grounds." Officials had spots narrowed by roughly a foot, to increase capacity, and introduced parking attendants.[10]

The crowd that throngs this building daily and nightly attest to the popularity of the motor car. Even those who cannot buy go to see. On Saturday night the building was jammed to capacity. It is one of the best people-pullers in the park.— anonymous writer, The Daily Star[10]

A 1928 Daily Star article published in the afternoon edition on Highways and Automotive Day pegged the total value of automobiles on display at over a million dollars. The CNE directors held a luncheon hosting "leaders in the automotive world". Speakers included the general manager of Canadian Goodyear Rubber Co., C. H. Carlisle,[10] and Dr. P. E. Doolittle, "well-known pathfinder" and president of the Canadian Automobile Association.[9][10] As a result of the popularity, there was talk of building a new automotive building, perhaps even in time for the next fair.[10] The CNE President noted he'd meet with members of the industry and civic authorities on the proposal.[9] The Globe noted that "sympathetic consideration of this exists in the minds of the City Council," noting the increase in overcrowding every year, but still was cautious about chances.[11]

A design contest was announced in later October 1928 and launched in early November, with the purpose of starting work in the winter so that the building would be complete in time for the 1929 CNE.[12] The contest received thirty potential designs for the structure. The winner, apparently winning by a slim point margin, was announced December 12, 1928, as being Douglas E. Kertland. Charles B. Dolphin won second place, and Mathers & Haldenby third. Deemed the "most elaborate automotive building in the world", the CNEA withheld the design until they could adjust the interior.[13][14]

It was to be built "immediately south" of the Electrical & Engineering Building.[13] Cost was estimated at $1 million upon announcement,[13] tendered at $1,000,299.26,[4] and $1,000,299 upon the beginning of construction.[15] Interior dimensions were set at 445 feet (136 m) long by 292 feet (89 m). The main storey was to offer 940,980 square feet (87,420 m2) of exhibition area, and the mezzanine floor 34,000 square feet (3,200 m2).[15] This was twice the area of the Electrical Building.[12] It was to feature "modern lighting of the indirect type."[15] It was to include a "public dining-room of sumptuous appointments."[15] Decorative iron work was to be used throughout.[15]

Construction work was underway as of early April 1929.[15] The Globe noted there was "no pomp or ceremony" to mark the start.[15] The cornerstone was laid June 12, 1929 by Sam Harris, VP, with invocation by Reverend F. C. Ward-Whate.[16] The building was opened August 26, 1929 by Ontario Premier Howard Ferguson.[17]

History

The building was initially used to display the latest car models to the public. The National Motor Show was last held in 1967.[8] In 1974, the Canadian International AutoShow appeared elsewhere in the city during the spring, closer in time to when new car models appear than in late August when the CNE starts.

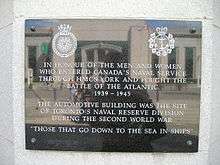

During World War II, this building was the home to Toronto's naval reserve, known as HMCS York. A commemorative plaque to this can be found on the north side of the building. In 1949, Maple Leaf Gardens builder and Toronto Maple Leafs owner Conn Smythe proposed converting the building into four ice arenas.[18]

In 1988, the building was designated a "listed" heritage structure.[19] In 1999, a study of the-then Direct Energy Centre determined that it had a lack of meeting space compared to other similar facilities in North America. In 2004, the CNE and City of Toronto approved a CA$47 million renovation of the Automotive Building so that it would provide the meeting space. It re-opened in 2009 as the Allstream Centre.[20] Since 2009, the building has been used exclusively for meetings, events and conferences.

Past uses

During the CNE:

- Art, manual education, home economics, and school projects from across the province, including work by auxiliary students and the disabled, in the Mezzanine. Displays moved there in 1939.[21]

- Seventh Annual Shirley Temple "movie double" competition[22]

- National Motor Show, 1929–1967[8]

- "Farm, Food and Fun" displays, which had previously been hosted in the Agricultural buildings north of Princes' Boulevard.

Through the rest of the year:

- American Hospital Association Convention

- Art Directors' Club of Toronto annual exhibition of Advertising and Editorial Art[23]

- Canadian Graphic Arts Show[24][25]

- Canadian Mobile Home and Travel Trailer Show[26]

- Canadian National Samples Show[27]

- Canadian Packaging Exposition,[28] later known as PacEx[29]

- Canadian Winter Sports Show[30]

- General Motors Motorama[31][32]

- National Automotive Parts and Equipment Show[33]

- Plastics Show of Canada[34]

- Toronto International Boat Show and National Marine Trade Show[35][36]

As Allstream Centre

- Annual "Dragon Ball"

- Juno Awards Dinner 2011

Gallery

- Exterior

-

North-west view of Automotive Building under construction in 1929.

-

South-west view of Automotive Building under construction in 1929.

-

View of Automotive Building from Lake Ontario shore in 1929.

-

View from southwest of Automotive Building in 1930.

-

Main (North) entrance in 2005.

-

South entrance in 2011.

-

Decorative iron work around windows.

-

HMCS York plaque.

- Interior

-

American Hospital Association Convention at Automotive Building in 1931.

-

A display of TTC vehicles inside the Automotive Building in 1936.

-

Interior of Automotive Building in 1937.

-

National Motor Show 1939

References

- 1 2 3 "Automotive Building will cost $1,000,299". The Globe and Mail. March 28, 1929. p. 14.

- ↑ "Public notice - Heritage land". City of Toronto. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Canada's Greenest Conference Centre". Allstream Centre. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- 1 2 "Automotive Building will cost $1,000,299". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 28 March 1929. p. 14.

- ↑ The reinvention of an auto palace, Toronto Star

- ↑ "Venue Details". Allstream Centre. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Floor Plans". Allstream Centre. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- 1 2 3 McIntosh, Jil. "Auto show history, from horses to Hitler". Wheels.ca. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Automotive Building On Exhibition Grounds Presaged By Bradshaw". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 28 August 1928. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Autos worth a million are shown at Exhibition". The Daily Star (5 O'Clock Edition). Toronto ON. 27 August 1928. p. 1.

- ↑ "Smart 1929 Car Models Attractively Displayed In Automotive Building". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 24 August 1928. p. 23.

- 1 2 "New Automotive Building To Be Erected This Winter". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 27 October 1928. p. 17.

- 1 2 3 "Douglas E. Kentland winner C.N.E. award". The Toronto Daily Star. Toronto ON. 12 December 1928. p. 23.

- ↑ "Win Awards in C.N.E. Automotive Competition". The Toronto Daily Star. Toronto ON. 13 December 1928. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "New automotive building under way". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 10 April 1929. p. 17.

- ↑ "New automotive building". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 11 June 1929. p. 13.

- ↑ "New automotive building at C.N.E. formally opened". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 27 August 1929. p. 15.

- ↑ "CNE Automotive Building May Be Converted Into Giant Hockey Palace". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 17 December 1949. p. 19.

- ↑ "Heritage Property Detail". City of Toronto. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Exhibition Place: Growth Strategies – Launch of a Privately Funded Convention Hotel" (PDF) (pdf). City of Toronto. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Judging of School Entries For C.N.E. Began Yesterday At New Automotive Building". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 20 June 1939. p. 11.

- ↑ "Captures First Place in Seventh Competition in Automotive Building at Exhibition". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 6 September 1937. p. 11.

- ↑ "2,000 Art Entries But Only 12 Prizes". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 12 October 1963. p. 16.

- ↑ "Briefly". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 19 July 1962. p. 26.

- ↑ "Graphic Arts Show Expected to Bring $5,000,000 in Sales". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 18 October 1963. p. B3.

- ↑ "Trailer Makers Want More, Better Camps". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 24 February 1965. p. B12.

- ↑ "Samples Show Called Success; Buyers Favor an Annual Basis". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 3 April 1963. p. 28.

- ↑ "Packaging Products on Display". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 6 November 1962. p. B3.

- ↑ "Color, Gadgets, Pretty Girls Pep Up Packaging Display". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 4 November 1964. p. B1.

- ↑ "Things to do and see during the weekend". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 5 November 1965. p. 12.

- ↑ "Motorama to Offer 30-Minute Musical". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 24 November 1960. p. 15.

- ↑ "Things to Do and See In Toronto at Weekend". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 25 November 1960. p. 17.

- ↑ "Wide Range Of Parts On Display". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 9 March 1965. p. B1.

- ↑ "People and Events". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 24 April 1961. p. 27.

- ↑ "Boat Show, Travelogues, Poetry Among Things To Do, See in Toronto at Weekend". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 2 February 1962. p. 21.

- ↑ "Huge supermarket for boating fans fills 4 Automotive Building at CNE". The Globe and Mail. Toronto ON. 3 February 1972. p. 45.