Culture of Algeria

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Algeria |

|---|

|

|

Maritime history • Military history • Economic history |

| People |

|

Traditions |

|

Mythology and folklore |

|

|

|

Writers • more |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

|

Monuments |

|

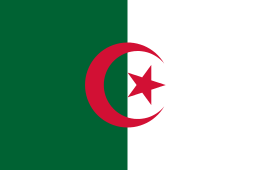

Symbols

|

|

The culture of Algeria encompasses literature, music, religion, cuisine and other facets of the Algerian lifestyle.

Religion

Algeria is a Muslim country, with Christian and Jewish minorities.

Cuisine

Algerian cuisine features cooking styles and dishes derived from traditional Arab, Amazigh, Turkish, and French cuisine. Additional influences of Jewish, Spanish, Berber and Italian cuisines are also found.[1] The cuisine is flavorful, often featuring a blend of traditional Mediterranean spices and chili peppers.[1] Couscous is a staple of the diet, often served with stews and other fare.

Literature

Modern Algerian literature, split between Arabic and French, has been strongly influenced by the country's recent history. Known poets in modern Algeria are Moufdi Zakaria, Mohammed Al Aid from the middle of the 20th century, and Achour Fenni and Azrag Omar in the late 1980s. Famous novelists of the 20th century include Mohammed Dib, Albert Camus, Kateb Yacine, and Ahlam Mosteghanemi, while Assia Djebar is widely translated. Among the important novelists of the 1980s were Rachid Mimouni, later vice-president of Amnesty International, and Tahar Djaout, murdered by an Islamist group in 1993 for his secularist views.[2]

In philosophy and the humanities, Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction, was born in El Biar in Algiers, Malek Bennabi and Frantz Fanon are noted for their thoughts on decolonization, Augustine of Hippo was born in Tagaste (modern-day Souk Ahras), and Ibn Khaldun, though born in Tunis, wrote the Muqaddima while staying in Algeria.

Algerian culture has been strongly influenced by Islam, the main religion. The works of the Sanusi family in pre-colonial times, and of Emir Abdelkader and Sheikh Ben Badis in colonial times, are widely noted. The Latin author Apuleius was born in Madaurus (Mdaourouch), in what later became Algeria.

Music

The Algerian musical genre best known abroad is raï, a pop-flavored, opinionated take on folk music, featuring international stars such as Khaled and Cheb Mami. In Algeria itself, raï remains the most popular, but the older generation still prefer shaabi, as performed by for instance Dahmane El Harrachi. While the tuneful melodies of Kabyle music, exemplified by Idir, Ait Menguellet, or Lounès Matoub, have a wide audience.

For more classical tastes, Andalusi music, brought from Al-Andalus by Morisco refugees, is preserved in many older coastal towns. For a more modern style, the English born and of Algerian descent, Potent C is gradually becoming a success for younger generations. Encompassing a mixture of folk, raï, and British hip hop, it is a highly collective and universal genre.

Although "raï" Check |url= value (help). is welcomed and praised as a glowing cultural emblem for Algeria, there was time when raï’s come across critical cultural and political conflictions with Islamic and government policies and practices, post-independency. Thus the distribution and expression of raï music became very difficult. However, “then the government abruptly reversed its position in mid-1985. In part this was due to the lobbying of a former liberation army officer turned pop music impresario, Colonel Snoussi, who hoped to profit from raï if it could be mainstreamed.”[3]

In addition, given both nations’ relations, Algerian government was pleased with the music’s growing popularity in France. Although the music is more widely accepted on the political level, it still faces severe conflictions with the populace of Islamic faith in Algeria.

Visual arts

1910: a generation of precursors

During the first half of the twentieth century, artists mainly recuperated models and patterns imported – or imposed – by an imperialist French power.[4]

As Edward Said argued in his book Orientalism in 1978, Algerian artists struggled with the perception and representations of Westerners. Almost a century after the conquest by the French, Azouaou Mammeri (1886–1954), Abdelhalim Hemche (1906–1978), Mohammed Zmirli (1909-1984), and Miloud Boukerche (1920–1979) were the first to introduce easel painting. They benefited from "breaches" in the educational system and were able to pursue a training in plastic arts. Even though they attempted to focus on the reality of Algerians' everyday routine, they were still to a certain extent incorporated in the orientalism movement.

The tradition of oriental illumination and miniature was introduced around the same period, through artists such as Mohamed Racim (1896–1974) or Mohamed Temman(1915-1988). It is the two main expression of figuration in a country where popular abstract symbolic, Berberian or Arabic, are integrated mainly through architecture, furnitures, weaving, pottery, leather and metal workmanship.

How to reappropriate one's own history is a dynamic in Algerian contemporary art, reflecting on the deep social changes people experienced.

Artists attempt a successful introspective work in which the duality in terms of identity creates a dynamic that overcomes "orientalism" and exotism. The main stake is for the artist and the spectator to reappropriate a liberty of expression and interpretation. Main artists of that period are: Boukerche, Benaboura, Ali Ali Khodja, Yelles, or Baya.

1930: a generation of founders

The vast majority of the artists incorporate the thematic of the independence war, from those who lived it to the artists that use it as a legacy. Impregnated by all the artistic and ideological movements that marked the first half of the twentieth century, artists are concerned with the society they live in and denounce segregation, racism and injustice that divided communities of colonial Algeria. A clear shift in operated from orientalism and exoticism: new themes such as the trauma and the pain appear, for instance in the portrait The Widow (1970) by Mohamed Issiakhem.

"Art is a form of resistance as it suggests and makes visible the invisible, the hidden, it stands alert on the side of life".[5]

It was also a time when Algerian artists start organizing themselves, through the National Union of Plastic Arts or UNAP (1963) for instance; artists such as Mohamed Issiakhem or Ali Khodja were part of it.

Non-figuration and "Painters of the Sign"

Abdallah Benanteur and Mohamed Khadda opened a path for abstract (non-figurative) Algerian art. They were French since childhood and emigrated to France. They were followed by artists such as Mohamed Aksouh, Mohamed Louail, Abdelkader Guermaz and Ali Ali-Khodja. Mohamed Khadda wrote[6] « If figurative painting appears as the norm in terms of expression, it is the result of an acculturation phenomenon». Artworks liberately figurative are a form of liberation in that sense, as literal representations do not seem to fully emerge from the cluster of exotism and orientalism.

The "Painters of the Sign" are Algerian artists born in the 1930s who, at the beginning of the 1960s, found inspiration in the abstract rhythm of Arabic writing. The term "peintres du Signe" was coined by the poet Jean Sénac in 1970. He was hosting in Alger the "Gallerie 54". The first collective exhibition reunited Aksouh, Baya, Abdallah Benanteur, Bouzid, Abdelkader Guermaz, Khadda, Jean de Maisonseul, Maria Manton, Martinez, Louis Nallard and Rezki Zérarti. He wrote in his presentation : "In this gallery 54, which aims at being a gallery of research in permanent contact with the people, we have brought together artists, Algerian or having deep links with our country" "We can assert, with Mourad Bourboune, that our artists do not only exhume the devastated face of our Mother, but, in the midst of the Nahda (renewal), they build a new image of the Man and stare endlessly at his new Vision"[7]

Aouchem

Algerian artists reconnected with part of their historical and cultural legacy, especially the influence of Berber culture and language. A great deal of attention was brought upon the Berber culture and identity revendications after the Berber Spring in 1988, and it impacted the cultural production. Denis Martinez and Choukri Mesli participated in the creation of the group Aouchem (Tattoo), which held several exhibitions in Algiers and Blida in 1967, 1968 et 1971. A dozen artists, painters and poets decided to oppose the mainstream organization of art – especially of figurative art, they believe to be represented by the UNAP, the National Union for Plastic Art. They opposed their policy of excluding many active painters. According to its manifesto : "Aouchem was born centuries ago, on the walls of a cave of Tassili. It continued its existence until today, sometimes secretly, sometimes openly, according to fluctuations of history. (...) We want to show that, always magical, the sign is stronger than bombs".[8]

In spite of a surge of political violence following the war of independence, where the hegemony of the Arabic culture and language tended to overlap on the berberian culture, the plastic traditions of popular signs managed to maintain. Aouchem builds on this traditional legacy.

Naivety and expressionism

Since the 1980s, there has been a renewal and also a form of "naivety", trying to go past the trauma of the war and address new contemporary issues. Baya (1931–1998) is the example of a great Algerian success story. Her work was prefaced by André Breton and exposed by André Meight when she was still a teenager. She who has not known her mother as she was doubly orphaned by the age of 5, produced colorful watercolors with fake symmetries, questioning the figure of the Mother. She is part of the art brut movement.

Expressionism was dominated by Mohamed Issiakhem, affectionately nicknamed "Oeil de lynx" (lynx eye) by his fellow writer Kateb Yacine. When he was 15, he had an accident with a grenade. Two of his sisters and his nephew died, his forearm had to be amputated. His personal drama resonates in work. He expressed themes like grief and loss through the use of thick pastes and universal figures; as an echo of the hardships of the Algerian war, as well as the universal struggle of those silenced and oppressed.

Renewal of visual arts

Since the 1980s, a new generation of Maghrebi artists has arisen. A large proportion is trained in Europe. Artists locally and among the Diaspora explore new techniques and face the challenges of a globalized art market. They are bringing together various elements of their identity, marked by the status of immigrant of first or second generation. They address issues that speak to the Arab world with an "outsider" lens. Kader Attia is one of them. He was born in France in 1970. In a large installation in 2007 called Ghost, he displayed dozens of veiled figures on their knees, made of aluminum fold.[9] Adel Abdessemed, born in Constantina in 1970, attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Algiers, Algeria and then Lyon, France. Through his conceptual artworks, he displays strong artistic statements using a wide range of media (drawing, video, photography, performance, and installation). In 2006, he exposed at the David Zimmer gallery in New York City. One of his artworks was a burnt car entitled Practice Zero Tolerance, a year after riots in France and in the midst of a resurgence of terrorist attacks since September 11, 2001. Katia Kameli also brings in the multiple aspects of her identity and environment, through video, photographs and installations.

Cinema

Sports

Football, handball, athletics, boxing, martial arts, volleyball and basketball are the most popular sports in the country.

See also

References

- 1 2 Farid Zadi. "Algerian cuisine". Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ↑ Tahar Djaout French Publishers' Agency and France Edition, Inc. (accessed 4 April 2006)

- ↑ Gross, Joan, David McMurray, and Ted Swedenburg. "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities." Diaspora 3:1 (1994): 3- 39. [Reprinted in The Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader, ed. by Jonathan Xavier and Renato Rosaldo.

- ↑ Bellido], [dir. de la publication: Ramon Tio (2003). Le XXe siècle dans l'art algérien : [exposition ... qui a eu lieu au Château Borély, Marseille, du 4 avril au 15 juin 2003, et à l'Orangerie du Sénat, Paris, du 18 juillet au 28 août 2003]. Paris: Aica Press [u.a.] ISBN 978-2-950676-81-8.

- ↑ Bouayed, Anissa (2005). L'art et l'Algérie insurgée : les traces de l'epreuve, 1954-1962. Alger: ENAG editions. ISBN 978-9961-623-93-0.

- ↑ Bernard, Michel-Georges (2002). Khadda. Alger: ENAG Editions. p. 48. ISBN 9789961623008.

- ↑ Dugas, Jean Sénac ; textes réunis par Hamid Nacer-Khodja ; préface de Guy (2002). Visages d'Algérie : Regards sur l'art. Paris: Paris-Méditerranée. ISBN 284272156X.

- ↑ "Aouchem manifesto". Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ "Kader Attia : la puissance du vide". Retrieved 2013-08-31.