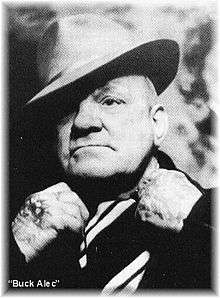

Alexander Robinson

Alexander "Buck Alec" Robinson (c. 1901–1995) was a boxer, Ulster loyalist paramilitary and Ulster Special Constabulary reservist. Robinson gained notoriety in Northern Ireland for streetfighting,[1][2] robbery[3] and for owning a pet lion. His contemporaries included James "Stormy" Wetherall and Patrick "Silver" McKee.[3]

Early life

Born on York Street in the Sailortown area of Belfast, Ireland, around 1901, Robinson's early life in the docks was indicative of his future problems with the law. In 1913 at the age of twelve, he was arrested on a charge of larceny.[3] In 1916 he was arrested three more times for the same offence. He was discharged on three out of four of these first offences, and received probation for the other.[3] He served in the British Merchant Navy towards the end of World War I. On his return to Belfast his criminal career expanded, being charged with assault, riotous behaviour and robbery by 1921.[3]

Career in the Ulster Special Constabulary

In October 1920 the British Government formed the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) after calls from Unionists for protection. This was to reinforce the Royal Irish Constabulary who, along with the Black and Tans, were fighting the Irish Republican Army in the Irish War of Independence.

The USC was formed on 1 November 1920, and consisted mainly of former Ulster Volunteers and other soldiers of the 36th (Ulster) Division who had served in World War I. Robinson was recruited to the USC's C1 section, which was made up of unpaid, non-uniformed reservists usually only called up in emergencies.[4]

Joe Graham of Rushlight Magazine has stated that Robinson was given the option of prison or joining up after assaulting a member of the wealthy Thompson family on the Glencairn Road, with Thompson's own hammer.[3] During this time Robinson claimed to have been Dawson Bates' bodyguard, who was Minister for Home Affairs in Sir James Craig's government.

He won his first significant amateur boxing bout at the King's Hall in 1922 representing the USC and would later go on to win the Irish middleweight championship in 1927.[5]

Interned

As well as being a Special Constable, Robinson was also a member of the loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Protestant Association. The group's aim, according to a police report of 1923, was "simply the extermination of Catholics by any and every means".[6] The police thought Robinson, who led a UPA group on Andrews street, was, "a dangerous gunman and leader of a murderous gang". In the press he was known as the "Docklands gunman and bomber" [7]

With the end of the Anglo-Irish war and partition in 1922, Robinson left the USC. After being implicated in several shootings and bombings he was interned in October 1922.[3] Several documents on his detention exist, including a letter from the RUC Commissioner recommending his internment:

"The respectable and law-abiding Protestants and Unionists residing in the area want to have these men taken from the locality at any cost, as they truly state there can be no peace so long as they are at large."

Another police report states:

"No matter what part of the City there is fighting in, he goes there to give a hand. He does not know what fear is, and would go any place to shoot and kill with either rifle, revolver or bomb."

The documents also contain other incidents Robinson was implicated in, including several shootings and a bombing. Robinson was released in 1923 and agreed to relocate to Bolton. He soon returned and was reinterned, and released again in late 1923.[8] His second release may have been secured through the promise that he would move to Chicago where he had relatives. In an interview with the north Belfast playwright Martin Lynch in the 1980s, Robinson claimed he worked for Al Capone and Joseph Kennedy.[5] He was later deported from the United States.[9]

Criminal convictions

Robinson was back in Belfast by the late 1920s. Writer Sam McAughtry recalled a banner reading "Welcome Home Buck Alec" being raised above York Street in the city.[5] His criminal convictions continued through to World War II. Around this time he acquired three lions.[10] Sources vary as to how these were acquired, one that they came from a visiting circus which Robinson allowed to use waste ground he owned at the rear of his house on Back Ship Street. Journalist Seth Linder writes that the lions were acquired from Dublin and Belfast Zoo, with Alec displaying them at a travelling circus throughout Ireland.[5] He kept the toothless lions at his home. Belfast folklore tells of him walking them on the streets of Sailortown. He continued to be known as a streetfighter into his fifties. Local newspapers regularly covered his fights in Belfast, the last known being in 1959. In court Robinson claimed he had knocked a man unconscious as he disagreed with the language he was using.

Death and tributes

Buck Alec continued to live in north Belfast until his death in 1995. Gusty Spence and Ian Paisley attended his funeral, the latter carrying the coffin and describing Robinson as "a rare character, a typical Ulsterman, an interesting facet of Ulster's history". A report in the Irish News focused on his paramilitary past. Other reports stated that "his heart was in the right place" and that Catholics attended his funeral alongside Protestants.

In his book Formations of Violence, Allen Feldman argues that Robinson was seen as a "hard man" who believed in a fair fight, rather than a common thug.[9]

References

- ↑ "Conflict Archive on the Internet". Sport and Community Relations in Northern Ireland. CAIN. 1995. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- ↑ Sugden, John (1996). Boxing and Society. Manchester University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7190-4321-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Buck Alec Robinson". Rushlight Magazine. 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- ↑ The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415-058-5

- 1 2 3 4 "North Belfast Partnership" (PDF). The Famous Faces of North Belfast. North Belfast Partnership. 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ↑ Alan F. Parkinson, Belfast's Unholy War, p279

- ↑ both refs from Parkinson p281

- ↑ http://www.theirishstory.com/2016/02/15/the-mad-dance-of-death-the-ulster-protestant-association-in-belfast-1921-22/

- 1 2 Feldman, Allen (1991). Formations of Violence. University of Chicago Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-226-24071-8.

- ↑ Brannagh, Kenneth (1989). Beginnings. University of Michigan. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7011-3388-7.