Alexander Og MacDonald, Lord of Islay

| Alexander Og MacDonald | |

|---|---|

| Lord of Islay | |

_(seal).jpg) Seal of Alexander Og MacDonald | |

| Reign | c.1293 – 1299 |

| Predecessor | Angus Mor MacDonald |

| Successor | Angus Og MacDonald |

| Died | 1299 |

| Wife |

|

| Dynasty | Clan Donald |

| Father | Angus Mor MacDonald |

Alexander Og MacDonald (died 1299), also known as Alexander of the Isles,[note 1] was a 13th-century Hebridean magnate. With the death of his father in about 1293, MacDonald succeeded as Lord of Islay, and the chiefship of the MacDonalds. During his tenure as chief, the lands of his family fell prey to the powerful Alexander MacDougall, Lord of Argyll, the chief of the MacDougalls. MacDonald and his younger brother entered into the service of Edward I, King of England, and made several appeals to the English king for aid against MacDougall. In fact, MacDonald may well have been married to a sister or daughter of MacDougall, and MacDonald and his wife fought a legal dispute against MacDougall over the island of Lismore. Although he is sometimes said to have lived into the 14th century, MacDonald may well have been slain in battle against MacDougall in 1299, and appears to have been succeeded by his younger brother, Angus Og MacDonald. MacDonald had six sons, and his descendants were noted gallowglass-warriors in Ireland. MacDonald is one of the earliest MacDonalds to bear a heraldic device.

Family and background

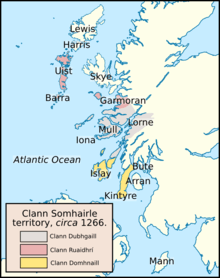

The eldest son of Angus Mor MacDonald, Lord of Islay (d. c.1293),[3] Alexander Og MacDonald was probably born during the reign of, and named after, Alexander III, King of Scots (d. 1286).[4] His younger brother was Angus Og MacDonald.[5] Alexander Og MacDonald's byname (Og) was probably used to differentiate him from his elder namesake-uncle, Alexander Mor MacDonald.[6][note 2] During Alexander III's reign, the MacDonalds were one of the most powerful kindreds on the western seaboard of Scotland. The MacDonalds (descended from Donald, son of Ranald, son of Somerled) were related to the MacRauris (descended from Ruari, son of Ranald, son of Somerled), and the extremely powerful MacDougalls (descended from Dugald, son of Somerled).

In the mid-13th century,[7] about the time of Alexander Og MacDonald's birth,[8] the islands on the western seaboard of Scotland were claimed by the Kingdom of Norway. After repeated attempts by the Scots kings to purchase the islands,[7] Scottish aggression into the region forced Hakon Hakonarson, King of Norway into action, who launched a massive military campaign to reassert Norwegian dominance. Although Hakon's forces gained in strength, as they sailed through the Hebrides, he received only lukewarm support from his vassals.[9] After an inclusive series of actions, on the Scottish mainland at Largs,[10] Hakon eventually turned for home, having accomplished little. Not long after Hakon's departure and death, Alexander III launched a punitive expedition into the Hebrides, and forced the submission of many of the leading magnates who had supported the Norwegian cause.[11] MacDonald's father was thus forced to hand him over as a hostage, to secure the good behaviour of the MacDonalds to the Scottish realm.[12] The provision of a nursemaid in the surviving documentary evidence suggests that MacDonald was only a young child at the time.[8] In 1266, through the Treaty of Perth, Alexander III finally purchased the islands from Magnus Hakonarson, King of Norway, and thus the island-territories of the MacDonalds (and their kinsmen) fell within the Kingdom of Scots.[13]

The Turnberry Band

With the death of Alexander III in March 1286, who left only a pregnant widow and an infant Norwegian-granddaughter, the succession to the Scottish throne was uncertain.[14] Although a panel of six guardians was appointed to govern the realm, factions soon solidified with competing claims to the throne.[15] In September 1286, one such claimant, Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale (d. 1295) gathered his associates at the seat of his son, Turnberry Castle, and concluded a bond of alliance, the so-called Turnberry Band.[16] Due to the vagness of the agreemant, the motivation behind the signatories is unknown for certain.[17] One interpretation of the alliance is that Bruce was rallying his supporters in preparation for his rise soon afterwards when, Alexander III's widow miscarried in November, and Bruce's forces rose in rebellion and took several castles in the south-west of Scotland, before order was finally restored by the guardians.[18]

Many of the distinguished signatories of the Turnberry Band were neighbours of Bruce, and two such signatory-neighbours were Alexander Og MacDonald and his father.[19][note 3] The document stipulated that all signatories should provide aid for two particular English magnates in Ireland: Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster (d. 1326), and Thomas de Clare, Lord of Thomond (d. 1287).[22] Of the signatories, the MacDonalds had the closest links to Ireland. Since these connections were closest with kindreds hostile to the Earl of Ulster, the bond may have been used as an instrument to keep the MacDonalds from supporting the enemies of the Anglo-Irish.[23][note 4]

Edward of England and Alexander of Argyll

When Alexander III's granddaughter died on her journey to Scotland in 1290,[25] the leading claimants to the Scottish throne were Bruce and John Balliol (d. 1314).[26] In 1291, Edward I, King of England, gained consent from the leading Scottish magnates to resolve the dispute through a judicial proceeding. In November 1292, the judgement went in favour of Balliol, who was thus duly enthroned King of Scots. Unfortunately for John, his ambitious English counterpart systematically undermined his authority, and Edward heard appeals on judgements made in Scotland.

In 1293, at his first parliament, John created three sheriffdoms: Skye, under the authority of William, Earl of Ross; Kintyre, under the authority of James Stewart; and Lorn, under the authority of Alexander MacDougall, Lord of Argyll (d. 1310).[27] The expansive territory of the MacDonalds spanned the regions under the authority of both Stewart and MacDougall. In about 1293, after his father's death, Alexander Og MacDonald appears to have succeeded to the chiefship of the family.[28] Along with his wife, Juliana, MacDonald is known to have been involved in a legal dispute with his powerful MacDougall namesake.[note 5] The first indication of such a dispute occurs in 1292, when MacDonald and MacDougall took their grievances over certain unknown lands to John. The outcome of this dispute is unknown, but MacDonald later appealed his case to King Edward, stating that John had occupied part of Lismore and refused to hand it over to him and his wife. Juliana is sometimes claimed to have been either a sister or daughter of MacDougall, and it has been thought possible that the contested lands formed part of her dowry.[29] However, other than her contested-claim on the island, there is little hard evidence to corroborate a familial-link to the MacDougalls.[30]

In 1296, after John ratified a military treaty with France, and refused to hand over Scottish castles to Edward's control,[26] the English marched north and crushed the Scots at Dunbar, after which Edward's forces proceeded forward virtually unopposed. Scotland thus fell under Edward's control.[31] Although MacDougall, like most Scots magnates, rendered homage to Edward in 1296, surviving evidence reveals that he was out of the English king's favour between the years 1296 and 1301. The reasons for MacDougall's fall from favour could well be related to his feuding with MacDonald.[29] Surviving sources show that MacDonald was acting as Edward's bailiff as early as April 1296. In this capacity, MacDonald was tasked to seize Kintyre, which had been escheated by John, and to hand the lands over to a certain Malcolm "le fiz Lengleys" ("son of the Englishman").[32][note 6] In a letter to King Edward in the summer of 1296, MacDonald queried the English king for clarification of his orders. He stated that he had already taken control of Kintyre, and was about to seize Stewart's castle,[34] which is thought to be Dunaverty Castle.[5] Unfortunately for scholars, Edward's reply is not known, but in September he is known to have awarded Alexander £100 worth of lands for "good service".[35]

In September 1296, King Edward commissioned Alexander Stewart, Earl of Menteith, to take MacDougall into custody. In May of the following year, MacDougall was released from imprisonment. By summer, MacDonald sent two letters to Edward, complaining that MacDougall and his associates were wreaking havoc throughout the region.[29] In his first letter, after reporting that MacDougall had wasted his lands, the chief of the MacDonalds begged Edward to order the lords of Argyll and Ross to help him in keeping peace in the region.[36] In the second letter, he reported the ongoing destruction committed by MacDougall, MacDougall's son Duncan, and MacDougall's brother-in-law John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch (d. 1303); he also complained that one of the king's escaped enemies, Lachlan MacRuari, had been aided by MacDougall, who had outfitted MacRuari with galleys; MacDonald concluded this letter by noting that the money which had been promised to him for his services had not yet been received.[37]

Confusion: death and the MacDonald chiefship

In about 1299, the Annals of Connacht,[38] the Annals of Loch Cé,[39] the Annals of the Four Masters,[40] and the Annals of Ulster[41] indicate that a certain "Alexander MacDonald" was slain in a particularly bloody battle by MacDougall.[42] For example, the Annals of Ulster describe the slain man as "the person who was best for hospitality and excellence that was in Ireland and in Scotland", and state that he fell "with a countless number of his own people that were slaughtered around him".[43] Although this man is generally thought to have been Alexander Og MacDonald,[44] another view is that man referred to was his elderly namesake-uncle Alexander Mor MacDonald.[45] If Alexander Og MacDonald did indeed fall in battle against his adversary MacDougall in 1299, this final clash was probably the bloody culmination of their drawn-out legal dispute of 1292.[46] In fact, MacDonald's demise at the hands of MacDougall is probably connected to the combined military actions of Hugh Bisset, John MacSween, and Angus Og MacDonald, recorded against the ever-dangerous Lord of Argyll not long afterwards.[47] With MacDonald's death, surviving sources indicate that the leadership of the family fell to his younger brother, Angus Og MacDonald. Thus in a letter to King Edward I in 1301, Angus Og MacDonald has the designation "de Yle" ("of Islay"), and conducted negotiations with the English king on his kindred's behalf.[46]

On the basis of a passage within Gesta Annalia II, which refers to the capture of a certain "Donald of the Isles",[48] it has sometimes been stated that Alexander Og MacDonald lived into the 14th century, and that he was captured in 1308 by Edward Bruce, Earl of Carrick (d. 1318).[49] However, this source's account of these particular events is confused,[50] and there is no definitive evidence to support the claim that MacDonald lived into the 14th century.[51][note 7] Confusingly, there is a record of a royal charter, generally thought to date from the reign of Robert I, King of Scots (d. 1329), to a certain "Alexander younger Lord of the Isles".[54] It is possible that this individual was either a nephew, or an otherwise unknown son and successor of Angus Og MacDonald.[55] Another possibility is that this was Alexander Og MacDonald himself—if this is the case, and the charter was indeed granted by Robert I, then MacDonald could not have perished in 1299.[54][note 8]

The Annals of Inisfallen[57] appear to indicate that an "Alexander MacDonald" was killed in the same year as Edward Bruce, who fell at the battle of Battle of Faughart in 1318.[58][note 9] Various Irish sources, such as the Annals of Clonmacnoise,[60] the Annals of Loch Cé,[61] and the Annals of Ulster,[62] state that alongside Bruce fell "MacRuari, King of the Hebrides" and "MacDonald, King of Argyll".[63][note 10] The identity of the latter is uncertain, although the title "King of Argyll" may be evidence that he was chief of the MacDonalds at this time.[65] It is possible that the accounts of "Alexander M" and "MacDonald, King of Argyll" could refer to the same man: perhaps the son/successor of Angus Og MacDonald (possibly recorded in Robert I's charter),[66] or else Alexander Og MacDonald himself (which would make him the man recorded in the said charter).[67] Another possibility is that the "Alexander M" and "MacDonald, King of Argyll" could refer to different men, the latter being Angus Og MacDonald.[68]

The identity of Donald MacDonald, significantly styled "of Islay" in several surviving sources, is uncertain.[69] He may have been an otherwise unknown son of Angus Mor MacDonald,[70] or an otherwise unknown son of Alexander Og MacDonald,[71] or else the son of Alexander Mor MacDonald.[72][note 11] Regardless of whether Alexander Og MacDonald fell in the 14th century or not, on the basis of the 14th century continuation of the chronicles of Nicholas Trevet, Donald MacDonald was among the slain at Faughart.[74]

Legacy

Alexander Og MacDonald had six sons.[75] By at least 1340, his descendants became noted gallowglass in Ireland.[76]

MacDonald and his father are the first of their family to bear heraldic devices.[77] Alexander's seal, which names him "S'ALEXANDRI DE ISLE", contains a lymphad with two men therein.[78]

Notes

- ↑ Scholars have rendered MacDonald's name variously in recent secondary sources: Alexander Óg,[1] and Alexander.[2] His name in modern Scottish Gaelic is Alasdair Òg MacDhòmhnaill.

- ↑ The Mediaeval Gaelic óc and óg (Anglicised oc and og) mean "young"; the Mediaeval Gaelic mór (Anglicised mor) means "big", "great".

- ↑ In fact, Bruce and his like-named son, witnessed a charter of MacDonald to Paisley Abbey, sometime in the reign of Alexander III.[20] This charter is probably the earliest historical record of the man who would later become Robert I, King of Scots.[21]

- ↑ The band may have also been used to insure de Clare's succession to the lands of his father-in-law, in the north-west of Ireland.[24]

- ↑ Like MacDonald, MacDougall was a first-born son, who was probably named after Alexander III.

- ↑ This Malcolm may be identical to the Malcolm MacQuillan who is recorded as holding lands in Kintyre, in 1306.[33]

- ↑ It may be significant that Alexander Og MacDonald is not mentioned within the The Brus, an important historical source composed by the 14th century historian John Barbour (d. 1395).[52] It is possible that the aforesaid account of "Donald of the Isles" preserved by Gesta Annalia II is related to Barbour's garbled and historically false account of the defeat, capture, imprisonment, and death of John MacDougall, Lord of Argyll (d. 1316), at the hands of Robert I, King of Scots (d. 1329).[53]

- ↑ On the other hand, if Alexander Og MacDonald received the charter from Edward I, rather than Robert I, then he could well have fallen in 1299.[56]

- ↑ Although the original Latin text reads "Alexander M", and doesn't preserve the man's surname or patronym, editors of the text have equated his surname to "MacDonald".[59]

- ↑ "MacRuari, King of the Hebrides" may refer to Ruairi MacRuairi, brother of Lachlan MacRuairi.[64]

- ↑ Although a certain "Donald" is recorded as a son Alexander Mor MacDonald, one of the sources for "Donald of Islay" gives Donald a brother named "Godfrey" (recorded in Latin "Gotherus", and in a Norman French version "Gotheri"), and Alexander Mor MacDonald is not known to have had a son so-named.[73]

Citations

- ↑ McDonald 1997.

- ↑ Barrow 1988. See also: Brown 2004. See also: Sellar 2004a.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: pp. 194. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 161.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 140.

- 1 2 McDonald 1997: p. 166.

- ↑ Lamont 1981: p. 168.

- 1 2 Stringer 2004.

- 1 2 McDonald 1997: p. 159 fn 5. Duffy 1991: p. 312.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 106–109.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 113–114. See also: Barrow 1981: pp. 117–118.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 115–116. See also: Barrow 1981: pp. 119–120.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 116, 159.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 120–121. See also: Barrow 1981: p. 120.

- ↑ Duncan 2004d. See also: Reid 2004. See also: Barrell 2003: pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Barrell 2003: pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 256. See also: Duncan 2004c. See also: Barrell 2003: p. 95.

- ↑ Barrell 2003: p. 95.

- ↑ Duncan 2004c.

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 256. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 161–162.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 162. See also: Innes 1832: pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Barrow 1988: p. 32.

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 256. See also: Duffy 2004.

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 256.

- ↑ Duffy 2004.

- ↑ Duncan 2004d.

- 1 2 Stell 2004.

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 258. See also: Barrell 2003: p. 105.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: p. 312.

- 1 2 3 Sellar 2000: p. 212. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 164.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 212 fn 128.

- ↑ Barrell 2003: pp. 106–107.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 166. See also: Bain 1884: p. 225 (#853).

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 259, 259 fn 6. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 166.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 166. See also: Simpson; Galbraith 1986: p. 152 (#152).

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 166. See also: Stevenson 1870b: p. 101 (#390).

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 164. See also: Bain 1884: pp. 235–236 (#904). See also: Stevenson 1870b: pp. 187–188 (#444).

- ↑ Sellar 2000: pp. 209, 212. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 164. See also: Bain 1884: p. 235 (#903). See also: Stevenson 1870b: pp. 189–191 (#445).

- ↑ "Annála Connacht – Annal 1299.2", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (25 January 2011 ed.), retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ "Annals of Loch Cé – Annal LC1299.1", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (5 September 2008 ed.), retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ "Annals of the Four Masters – Annal M1299.3", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (3 September 2008 ed.), retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ "Annala Uladh: Annals of Ulster otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senat – Year U1295.1", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (25 January 2011 ed.), retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Campbell of Airds 2000: p. 61. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 212. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 169. See also: Lamont 1981: p. 168.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 212. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 169.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 212. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 169. See also: Duffy 1991: p. 312 fn 52.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 168–169 fn 36. See also: Duffy 1991: p. 312.

- 1 2 McDonald 1997: p. 169.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 167, 169. See also: Stevenson 1870b: p. 435 (#610).

- ↑ Skene 1872: p. 337.

- ↑ Duncan 2004a. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 169.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 169. See also: Lamont 1981: pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 212, 217 fn 156. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 169.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 169. See also: Lamont 1981: p. 164.

- ↑ Sellar 2004b. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 217 fn 156. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 181. See also: Eyre-Todd 1907: p. 260.

- 1 2 Duffy 1991: p. 312. See also: Lamont 1981: p. 168.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 184. See also: Barrow 1988: p. 291. See also: Lamont 1981: p. 168.

- ↑ Lamont 1981: p. 169.

- ↑ "Annals of Inisfallen", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (2010-02-16 ed.), retrieved 4 February 2012. See also: "Annals of Inisfallen", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (in English, Irish, and Latin) (23 October 2008 ed.), retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 187.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 187 fn 112. See also: Duffy 1991: p. 312 fn 51.

- ↑ Murphy 1896: p. 281.

- ↑ "Annals of Loch Cé – Annal LC1318.7", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (5 September 2008 ed.), retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ "Annala Uladh: Annals of Ulster otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senat", CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts (www.ucc.ie/celt) (25 January 2011 ed.), retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: p. 312. See also: Barrow 1988: pp. 290–291 (and also 377) fn 103.

- ↑ Barrow 1988: pp. 290–291 (and also 377) fn 103.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 187–188.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: pp. 188.

- ↑ Lamont 1981: pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Brown 2004: p. 265.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: p. 311. See also: Barrow 1988: pp. 163, 291, 360 fn 124. See also: Lamont 1981: p. 165.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: p. 311. See also: Barrow 1988: pp. 163, 290. See also: Lamont 1981: p. 165. See also: Barrow 1973: p. 380.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: p. 311.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: pp. 311–312.

- ↑ Duffy 1991: p. 311–312. See also: Lamont 1981: pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Duffy 1991.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 194.

- ↑ Nicholls 2005: pp. 291–292.

- ↑ McAndrew 2006: pp. 66–67.

- ↑ McAndrew 2006: pp. 66–67. See also: Macdonald 1904: p. 227 (#1793). See also: Bain 1884: p. 145 (#622, #623). See also: Laing 1866: p. 91 (#536).

References

- Primary sources

- Bain, Joseph, ed. (1884), Calendar of documents relating to Scotland, 2, H. M. General Register House.

- Eyre-Todd, George, ed. (1907), The Bruce, Gowans & Gray.

- Innes, Cosmo, ed. (1832), Registrum monasterii de Passelet, Maitland Club.

- Murphy, Denis, ed. (1896), The annals of Clonmacnoise, printed for the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.

- Skene, William Forbes, ed. (1872), John of Fordun's chronicle of the Scottish nation, Edmonston and Douglas.

- Simpson, Grant G.; Galbraith, James D., eds. (1986), Calendar of documents relating to Scotland, 5, Scottish Record Office.

- Stevenson, Joseph, ed. (1870a), Documents illustrative of the history of Scotland, 1, H. M. General Register House.

- Stevenson, Joseph, ed. (1870b), Documents illustrative of the history of Scotland, 2, H. M. General Register House.

- Secondary sources

- Barrell, Andrew D. M. (2003), Medieval Scotland, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0 511 01720 0.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1973), The kingdom of the Scots: government, church and society from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, St. Martin's Press.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1981), Kingship and unity: Scotland 1000–1306, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0 8020 6448 5.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1988), Robert Bruce and the community of the realm of Scotland (3rd ed.), Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9780748620227.

- Brown, Michael (2004), The wars of Scotland, 1214–1371, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9780748612383.

- Campbell of Airds, Alastair (2000), A history of Clan Campbell, 1, Polygon, ISBN 1 902930 17 7.

- Duffy, Seán (1991), "'Continuation' of Nicholas Trevet: A New Source for the Bruce Invasion", Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Royal Irish Academy: 303–315, JSTOR 25516086.

- Duffy, Seán (2004), "Burgh, Richard de, second earl of Ulster (b. in or after 1259, d. 1326)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3995, retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Dunbar, JG; Duncan, AAM (1971). "Tarbert Castle: A Contribution to the History of Argyll". The Scottish Historical Review. 50 (1): 1–17. JSTOR 25528888 – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- Duncan, Archibald Alexander McBeth (2004c), "Brus, Robert (V) de, lord of Annandale (c.1220–1295)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)) (online January 2008 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3752, retrieved 22 January 2012.

- Duncan, Archibald Alexander McBeth (2004d), "Margaret [the Maid of Norway] (1282/3–1290)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18048, retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Laing, Henry (1866), Supplemental descriptive catalogue of ancient Scottish seals, Edmonston and Douglas.

- Lamont, W. D. (1981), "Alexander of Islay, Son of Angus Mór", The Scottish Historical Review, 60 (170, part 2): 160–169, JSTOR 25529420.

- Macdonald, William Rae (1904), Scottish armorial shields, William Green and Sons.

- McAndrew, Bruce A. (2006), Scotland's historic heraldry, Boydell Press, ISBN 9781843832614.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (1997), The kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's western seaboard, c.1100–c.1336, Scottish Historical Monographs, Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1 898410 85 2.

- Nicholls, Kenneth (2005), "Mac Domnaill (Macdonnell)", in Duffy, Seán; MacShamhráin, Ailbhe; Moynes, James, Medieval Ireland: an encyclopedia, Routledge, p. 291–292, ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Prestwich, Michael (2004), "Edward I (1239–1307)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)) (online January 2008 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8517, retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Reid, Norman H. (2004), "Alexander III (1241–1286)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)) (online May 2011 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/323, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2000), "Hebridean sea kings: The successors of Somerled, 1164–1316", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, Russell Andrew, Alba: Celtic Scotland in the middle ages, Tuckwell Press, pp. 187–218, ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2004a), "MacDougall, Alexander, lord of Argyll (d. 1310), magnate", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49385, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2004b), "MacDougall, John, lord of Argyll (d. 1316)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54284, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Stell, G. P. (2004), "John [John de Balliol] (c.1248x50–1314)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)) (online October 2005 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1209, retrieved 6 September 2011.

- Stringer, Keith John (2004), "Alexander II (1198–1249)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/322, retrieved 5 July 2011.

External links

| Preceded by Angus Mor MacDonald |

Lord of Islay c.1293 – 1299 |

Succeeded by Angus Og MacDonald |