Ai-Khanoum

|

Gold coin of Eucratides I (171–145 BC), one of the Hellenistic rulers of ancient Ai-Khanoum. This is the largest gold coin minted in Antiquity. | |

Shown within Afghanistan | |

| Alternate name | Ay Khanum |

|---|---|

| Location | Takhar Province, Afghanistan |

| Region | Bactria |

| Coordinates | 37°10′10″N 69°23′30″E / 37.16944°N 69.39167°ECoordinates: 37°10′10″N 69°23′30″E / 37.16944°N 69.39167°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | circa 280 BC, 3rd century BC |

| Abandoned | Possibly between 145 and 120 BC |

| Periods | Hellenistic |

| Cultures | Greek |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | Between 1964 and 1978 |

| Archaeologists | Paul Bernard |

| Condition | Ruined |

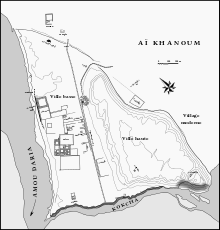

Ai-Khanoum or Ay Khanum (lit. “Lady Moon” in Uzbek,[1] possibly the historical Alexandria on the Oxus, also possibly later named اروکرتیه or Eucratidia) was one of the primary cities of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Previous scholars have argued that Ai Khanoum was founded in the late 4th century BC, following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Recent analysis now strongly suggests that the city was founded c. 280 BC by the Seleucid king Antiochus I.[2][3] The city is located in Takhar Province, northern Afghanistan, at the confluence of the Oxus river (today's Amu Darya) and the Kokcha river, and at the doorstep of the Indian subcontinent. Ai-Khanoum was one of the focal points of Hellenism in the East for nearly two centuries, until its annihilation by nomadic invaders around 145 BC about the time of the death of Eucratides.[4]

The site was excavated through archaeological searches by a French DAFA mission under Paul Bernard between 1964 and 1978, as well as Russian scientists. The searches had to be abandoned with the onset of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, during which the site was looted and used as a battleground, leaving very little of the original material.

Strategic location

The choice of this site for the foundation of a city was probably guided by several factors. The region, irrigated by the Oxus, had a rich agricultural potential. Mineral resources were abundant in the back country towards the Hindu Kush, especially the famous so-called "rubies" (actually, spinel) from Badakshan, and gold. Its location at the junction between Bactrian territory and nomad territories to the north, ultimately allowed access to commerce with the Chinese empire. Lastly, Ai-Khanoum was located at the very doorstep of Ancient India, allowing it interact directly with the Indian subcontinent.

A Greek city in Bactria

Numerous artifacts and structures were found, pointing to a high Hellenistic culture, combined with Eastern influences. "It has all the hallmarks of a Hellenistic city, with a Greek theatre, gymnasium and some Greek houses with colonnaded courtyards" (Boardman). Overall, Aï-Khanoum was an extremely important Greek city (1.5 sq kilometer), characteristic of the Seleucid Empire and then the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. It seems the city was destroyed, never to be rebuilt, about the time of the death of the Greco-Bactrian king Eucratides around 145 BC.

Ai-Khanoum may have been the city in which Eucratides was besieged by Demetrius, before he successfully managed to escape to ultimately conquer India (Justin).

Architecture

The mission unearthed various structures, some of them perfectly Hellenistic, some other integrating elements of Persian architecture:

- Two-miles long ramparts, circling the city

- A citadel with powerful towers (20 × 11 metres at the base, 10 meters in height) and ramparts, established on top of the 60 meters-high hill in the middle of the city

- A Classical theater, 84 meters in diameter with 35 rows of seats, that could sit 4,000-6,000 people, equipped with three loges for the rulers of the city. Its size was considerable by Classical standards, larger than the theater at Babylon, but slightly smaller than the theater at Epidaurus.

- A huge palace in Greco-Bactrian architecture, somehow reminiscent of formal Persian palatial architecture

- A gymnasium (100 × 100m), one of the largest of Antiquity. A dedication in Greek to Hermes and Herakles was found engraved on one of the pillars. The dedication was made by two men with Greek names (Triballos and Strato, son of Strato).

- Various temples, in and outside the city. The largest temple in the city apparently contained a monumental statue of a seated Zeus, but was built of the Zoroastrian model (massive, closed walls instead of the open column-circled structure of Greek temples).

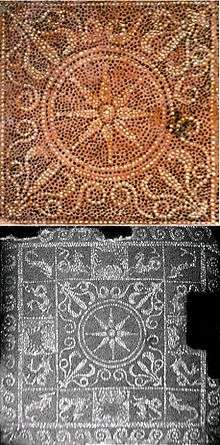

- A mosaic representing the Macedonian sun, acanthus leaves and various animals (crabs, dolphins etc...)

- Numerous remains of Classical Corinthian columns

-

Architectural antefixae with Hellenistic "Flame palmette" design, Ai-Khanoum.

-

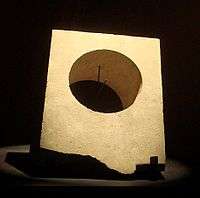

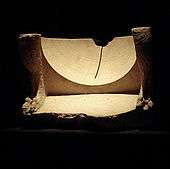

Sun dial within two sculpted lion feet.

-

Winged antefix, a type only known from Ai-Khanoum.

Sculptural remains

Various sculptural fragments were also found, in a rather conventional, classical style, rather impervious to the Hellenizing innovations occurring at the same time in the Mediterranean world.

Of special notice, a huge foot fragment in excellent Hellenistic style was recovered, which is estimated to have belonged to a 5-6 meter tall statue (which had to be seated to fit within the height of the columns supporting the Temple). Since the sandal of the foot fragment bears the symbolic depiction of Zeus' thunderbolt, the statue is thought to have been a smaller version of the Statue of Zeus at Olympia.

Also found among the sculptural remains were:

- A statue of a standing female in a rather archaic chiton

- The face of a man, sculpted in stucco

- An unfinished statue of a young naked man with wreath

- A gargoyle head representing the Greek cook-slave

- A frieze of a naked man, possibly the god Hermes, wearing a chlamys

- A hermaic sculpture of an old man thought to be a master of the gymnasium, where it was found. He used to hold a long stick in his left hand, symbol of his function.

Due to the lack of proper stones for sculptural work in the area of Ai-Khanoum, unbaked clay and stucco modeled on a wooden frame were often used, a technique which would become widespread in Central Asia and the East, especially in Buddhist art. In some cases, only the hands and feet would be made in marble.

-

Sculpture of an old man. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

-

Bust of the same man.

-

Frieze of a naked man wearing a chlamys. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

-

Same frieze, seen from the side.

-

Hellenistic gargoyle. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Epigraphic remains

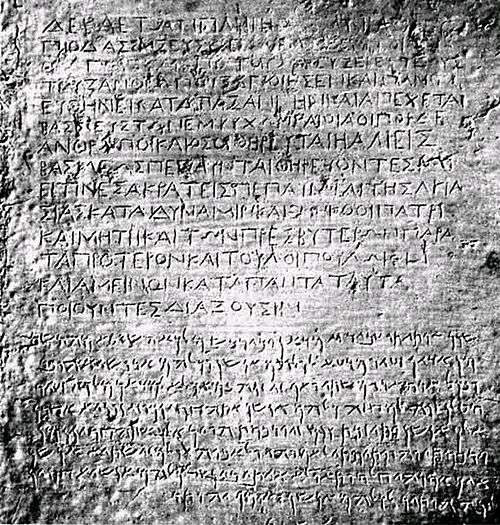

Various inscriptions in Classical, non-barbarized, Greek have been found in Ai-Khanoum.

- On a Herõon (funerary monument), identified in Greek as the tomb of Kineas (also described as the oikistes (founder) of the Greek settlement) and dated to 300-250 BC, an inscription has been found describing Delphic precepts:

- "Païs ôn kosmios ginou (As children, learn good manners)

- hèbôn enkratès, (as young men, learn to control the passions)

- mesos dikaios (in middle age, be just)

- presbutès euboulos (in old age, give good advice)

- teleutôn alupos. (then die, without regret.)"

The precepts were placed by a Greek named Clearchos, possibly Clearchus of Soli the disciple of Aristotle, who, according to the same inscription, had copied them from Delphi:

- "These wise commandments of men of old

- - Words of well-known thinkers - stand dedicated

- In the most holy Pythian shrine

- From there Klearchos, having copied them carefully, set them up, shining from afar, in the sanctuary of Kineas"

- Remains of some papyrus manuscripts, the imprint of which were left in the thin earth of brick walls, containing unknown philosophical dialogues on the theory of ideas, thought to be the only surviving remain of an Aristotelian dialogue, possibly the Sophist, where Xenocrates, another philosopher, present his theory of ideas.[5]

- Various Greek inscriptions were also found in the Treasury of the palace, indicating the contents (money, imported olive oil...) of various vases, and names of the administrators in charge of them. The hierarchy of these administrators appears to be nearly identical to that in the Mediterranean Greek areas. From the names mentioned in these inscriptions, it appears that the directors of the Treasury were Greek, but that lower administrators had Bactrian names.[5] Three signatories had Greek names (Kosmos, Isidora, Nikeratos), one a Macedonian or Thracian name (Lysanias), and two Bactrian names (Oxuboakes, Oxubazes).

One of these economic inscriptions relates in Greek the deposit of olive oil jars in the treasury:

- "In the year 24, on ....;

- an olive oil (content);

- the partially empty (vase) A (contains) oil transferred from

- two jars by Hippias

- the hemiolios; and did seal:

- Molossos (?) for jar A, and Strato (?) for jar B (?)"[5]

The last of the dates on these jars has been computed to 147 BC, suggesting that Ai-Khanoum was destroyed soon after that date.

Artifacts

Numerous Greco-Bactrian coins were found, down to Eucratides, but none of them later. Ai-Khanoum also yielded unique Greco-Bactrian coins of Agathocles, consisting of six Indian-standard silver drachms depicting Hindu deities. These are the first known representations of Vedic deities on coins, and they display early Avatars of Vishnu: Balarama-Samkarshana and Vasudeva-Krishna, and are thought to correspond to the first Greco-Bactrian attempts at creating an Indian-standard coinage as they invaded northern India.

Among other finds:

- A round medallion plate describing the goddess Cybele on a chariot, in front of a fire altar, and under a depiction of Helios

- A fully preserved bronze statue of Herakles

- Various golden serpentine arm jewellery and earrings

- Some Indian artifacts, found in the treasure room of the city, probably brought back by Eucratides from his campaigns

- A toilet tray representing a seated Aphrodite

- A mold representing a bearded and diademed middle-aged man

Various artifacts of daily life are also clearly Hellenistic: sundials, ink wells, tableware. An almost life-sized dark green glass phallus with a small owl on the back side and other treasures are said to have been discovered at Ai-Khanoum, possibly along with a stone with an inscription, which was not recovered. The artifacts have now been returned to the Kabul Museum after several years in Switzerland by Paul Bucherer-Dietschi, Director of the Swiss Afghanistan Institute.[6]

-

Bronze Herakles statuette. Ai-Khanoum. 2nd century BC.

-

Bracelet with horned female busts. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

-

Stone recipients from Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

-

Imprint from a mold found in Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

Trade with the Mediterranean

The presence of olive oil jars at Ai-Khanoum indicates that this oil was imported from the Mediterranean, as its only possible source would have been the Aegean Basin or Syria. This suggests important trade contacts with the Mediterranean, through long and expensive land routes.[7]

Contacts with India

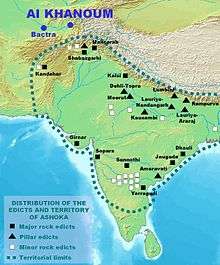

As the southern part of Afghanistan up to the Hindu Kush (Paropamisadae) seems to have been occupied by the Mauryan Empire between 305 BC until the reconquest by Demetrius in 180 BC, Ai-Khanoum was in effect a frontier town, located just a few kilometers from Indian dominions, for more than a century.

Several Indian artifacts were found among the archaeological remains of Ai-Khanoum, especially a narrative plate made of shell inlaid with various materials and colors, thought to represent the Indian myth of Kuntala.[8]

In Ai-Khanoum Greek remarkable coins were also found, of one of the last Greco-Bactrian kings, Agathocles of Bactria (ruled 190-180 BCE). They are Indian-standard square coins bearing the first known representations of Indian deities, which have been variously interpreted as Vishnu, Shiva, Vasudeva, Buddha or Balarama. Altogether, six such Indian-standard silver drachmas in the name of Agathocles were discovered at Ai-Khanoum in 1970.[9][10][11] Some other coins by Agathocles are also thought to represent the Buddhist lion and the Indian goddess Lakshmi.[12] The Indian coinage of Agathocles is few but spectacular. These coins at least demonstrate the readiness of Greek kings to represent deities of foreign origin. The dedication of a Greek envoy to the cult of Garuda at the Heliodorus pillar in Besnagar could also be indicative of some level of religious syncretism.

The various sun-dials, including a tropical sundial adjusted to the latitude of Ujjain found in the excavations also suggest that some transmission into Indian astronomy may have happened, due to the numerous interactions with the Mauryan Empire, and the later expansion of the Indo-Greeks into India.[13]

Influence on Indian art

Ai-Khanoum being located at the doorstep of India, interacting with the Indian subcontinent, and having a rich Hellenistic culture, was in a unique position to influence Indian culture as well. It is considered that Ai-Khanoum may have been one of the primary actors in transmitting Western artistic influence to India, for example in the creation of the Pillars of Ashoka or the manufacture of the quasi-Ionic Pataliputra capital, all of which were posterior to the establishment of Ai-Khanoum.[14]

The scope of adoption goes from designs such as the bead and reel pattern, the central flame palmette design and a variety of other moldings, to the life-like rendering of animal sculpture and the design and function of the Ionic anta capital in the palace of Pataliputra.[15]

Numismatics

Many Seleucid and Bactrian coins were found at Ai-Khanoum, as were ten blank planchets, indicating that there was a mint in the city.[16] Ai-Khanoum apparently had a city symbol (a triangle within a circle, with various variations), which was found imprinted on bricks coming from the oldest buildings of the city.

The same symbol was used on various Seleucid eastern coins, suggesting that they were probably minted in Ai-Khanoum. Numerous Seleucid coins were thus reattributed to the Ai-Khanoum mint rather recently, with the conclusion that Ai-Khanoum was probably a larger minting center than even Bactra.[17]

The coins found in Ai-Khanoum start with those of Seleucus, but end abruptly with those of Eucratides, suggesting that the city was conquered at the end of his rule.

Nomadic invasions

The invading Indo-European nomads from the north (the Scythians and then the Yuezhi) crossed the Oxus and subdued Bactria about 135 BC. It seems the city was totally abandoned between 130 and 120 BC following the Yuezhi invasion. There is evidence of huge fires in all the major buildings of the city. The last Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles moved his capital from Balkh around 125 BC and resettled in the Kabul valley. No coins of Heliokles have been found in Ai-Khanoum, suggesting the city was destroyed at the end of the reign of Eucratides. The Greeks continued to rule various parts of northern India under the Indo-Greek Kingdom until around 10 CE, when their last kingdom was conquered by the Indo-Scythians. Only a few decades later, the Yuezhi united to form the Kushan Empire and expanded in northern India themselves.

As with other archaeological sites such as Begram or Hadda, the Ai-Khanoum site has been pillaged during the long phase of war in Afghanistan since the fall of the Communist government.

Significance

The findings are of considerable importance, as no known remain of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek civilizations had been uncovered in the East (beyond the abundant coinage) until this discovery, leading some to speak about a "Bactrian mirage."

Ai-Khanoum was a center of Hellenistic culture at the doorstep of India, and there was a strong reciprocal awareness between the two areas. A few years after the foundation of the city, around 258 BC, the Indian Emperor Ashoka was carving a rock inscription in Greek and Aramaic destined to the Greeks in the region, the Kandahar Edict of Ashoka, in the nearby city of Kandahar.

The discovery of Ai-Khanoum also gives a new perspective on the influence of Greek culture in the East, and reaffirms the influence of the Greeks on the development of Greco-Buddhist art.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ai-Khanoum. |

Notes

- ↑ Bell, George. "Journal of the Royal Society of Arts". Royal Society of Arts, 1970. p. 445

- ↑ Lyonnet, Bertille. "Questions on the Date of the Hellenistic Pottery from Central Asia (Ai Khanoum, Marakanda and Koktepe". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia". vol. 18. 2012. pp. 143-173.

- ↑ Martinez-Seve, Laurianne. "The Spatial Organization of Ai Khanoum, a Greek City in Afghanistan". American Journal of Archaeology 118.2. 2014. pp 267-283.

- ↑ Bernard, P. (1994): "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 92-3-102846-4, p. 103.

- 1 2 3 Claude Rapin, "De l'Indus à l'Oxus", p375. Also full description of the papyrii (French)original text and French translation

- ↑ Source, BBC News, Another article. German story with photographs here (translation here).

- ↑ Frölich, p.10

- ↑ "Afghanistan, tresors retrouves", p150

- ↑ Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia, Frank Lee Holt, Brill Archive, 1988, p.2

- ↑ Iconography of Balarāma, Nilakanth Purushottam Joshi, Abhinav Publications, 1979, p.22

- ↑ The Hellenistic World: Using Coins as Sources, Peter Thonemann, Cambridge University Press, 2016, p.101

- ↑ The Hellenistic World: Using Coins as Sources, Peter Thonemann, Cambridge University Press, 2016, p.101

- ↑ "Les influences de l'astronomie grecques sur l'astronomie indienne auraient pu commencer de se manifester plus tôt qu'on ne le pensait, dès l'époque Hellénistique en fait, par l'intermédiaire des colonies grecques des Gréco-Bactriens et Indo-Grecs" (French) Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés", p269. Translation: "The influence of Greek astronomy on Indian astronomy may have taken place earlier than thought, as soon as the Hellenistic period, through the agency of the Greek colonies of the Greco-Bactrians and the Indo-Greeks.

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", p.15

- ↑ John Boardman, "The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture", p.13-22

- ↑ Brian Kritt: Seleucid Coins of Bactria, p. 22.

- ↑ "Seleucid coins of Bactria", Brian Kritt

References

- Tarn, W. W. (1984). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Chicago: Ares. ISBN 0-89005-524-6.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 2-9516679-2-2.

- Frölich, Pierre (2004). Les Grecs en Orient. L'heritage d'Alexandre. La Documentation photographique, n.8040 (in French). Paris: La Documentation Francaise.

- Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul (2008). Eds., Friedrik Hiebert and Pierre Cambon. National Geographic, Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-1-4262-0374-9.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ai-Khanoum. |

- Ai-Khanum, the Capital of Eucratides on Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Ai-Khanoum archaeological site photographs

- Ai-Khanoum and vandalization during the Afghan war page not found

- The Hellenistic Age

- Afghan Treasures

- 3-D reconstruction of Ai-Khanoum

- Livius.org: Alexandria on Oxus

- Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World Surviving treasures from the National Museum of Afghanistan, at The British Museum, 3 March – 17 July 2011