Agkistro

| Agkistro Άγκιστρο | |

|---|---|

Agkistro | |

|

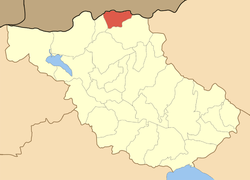

Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 41°23′N 23°45′E / 41.383°N 23.750°ECoordinates: 41°23′N 23°45′E / 41.383°N 23.750°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Serres |

| Municipality | Sintiki |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 373 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Vehicle registration | ΕΡ |

Agkistro or alternatively Agistro (Greek: Άγκιστρο, pronounced [ˈaɟistɾo]), is a village in the Serres regional unit, Greece. The village is part of the municipality of Sintiki[2] and hosts a population of 373, according to the 2011 census.[1] Agistro lies near the Greek-Bulgarian border and 10 km from the border crossing of Promachonas.[3] The village main tourist attraction is its steam bath complex, which dates from the Byzantine period.[3][4]

History

The gold and silver mines found in the mountain of Agkistro, south of the modern village, are believed to have provided valuable material to the armies of Ancient Macedon and especially to the campaign of Alexander the Great, during the 4th century BC,[5] although in archaeological bibliography the specific location has not been identified as one of the ancient mining sites.[6] The steam bath complex and tower in the village center were erected during the Byzantine period, ca. 950 AD.[5] The latter was later converted into a 20 m high clock tower, possibly during the reign of Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos (1328–1341).[7]

During Ottoman times the village was known as Tsigkeli (Turkish: Çengel), while the baths were modified for use by the local Ottoman lord and his harem.[5] Additionally the clock tower was used as a jail and place of executions.[7] In a survey of 1877 by the French professor A. Synvet,[8] the village was home to 200 Greeks;[9] while in a survey of 1905, by the Secretary General of the Bulgarian Exarchate, who expressed the Bulgarian point of view,[10][11][12] the village was inhabited by 1,536 Bulgarians and had a Bulgarian school,[13] which is also confirmed by a map by the Italian Institute Geografico de Agostini of the Christian schools in Macedonia.[14] When the Balkan Wars ended in 1913, the Greek-Bulgarian border was drawn a few metres north of the village. In the years that followed, due to tensions in Greek-Bulgarian relations, the village was to be found within a military zone.[5]

In 1920 the local population was 965. In 1923 a number of refugees arrived from the Pontus region, as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, resulting in a population increase (1,240 in 1928).[5] South of the village lies Rupel Fort, which was part of the Greek line of defense that withstood the German invasion in the spring of 1941, during World War II.[3]

Agkistro formed a separate community, but during the local government reforms of 2011 it was incorporated within the Sintiki municipality, of which it is a municipal unit.[2]

Main sights

Around 100,000 tourists visit on an annual basis.[15] Despite the general financial crisis in Greece, there is no local unemployment, with over thirty businesses catering to the tourist industry. The main attraction is the Byzantine spa complex which has been recently renovated.[16][17]

In Fort Rupel, which is today a war museum, memorial celebrations are held every 6 April.[18][19]

References

- 1 2 "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- 1 2 Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (Greek)

- 1 2 3 ekathimerini.gr Pamper yourself in Serres: Village of Agistro offers steam baths and more Archived January 31, 2011, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Unbekanntes Griechenland: Das besondere Erlebnis" (PDF). Griechenland Aktuell:. January 13, 2011. p. 6. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Άγκιστρο - Ιστορική Αναδρομή". Δήμος Σιντικής. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ Hammond, N.G.L; Griffith, G.T (1979). A history of Macedonia Vol.2, 550-336. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 72ff. ISBN 9780198148142.

- 1 2 Τουριστικές διαδρομές (PDF) (in Greek). Περιφερειακή Ενότητα Σερρών. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ↑ Archaeology, anthropology, and heritage in the Balkans and Anatolia: the life and times of F.W. Hasluck, 1878-1920, Volume 2; David Shankland; 2004; p.281

- ↑ Synvet, A. (1877). Les Greks de l'Empire Ottoman (PDF). Constantinople. p. 48.

- ↑ Zartman, edited by I. William (2010). Understanding life in the borderlands boundaries in depth and in motion ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780820334073.

- ↑ Dakin, Douglas (1966). The Greek struggle in Macedonia, 1897-1913. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 20.

- ↑ Bowman, Isaiah (1922). The new world: problems in political geography. World book company. p. 591.

- ↑ D.M. Brancoff. La Macédoine et sa Population Chrétienne, 1905, p.188 (marked as Senguelovo) (French)

- ↑ Map of the Italian Instituto Geografico de Agostini, showing the distribution of schools, churches, monasteries in the Ottoman vilayet of Saloniki.

- ↑ tanea.gr Ποια κρίση; Εδώ δεν υπάρχει άνεργος.

- ↑ Management Authority of Lake Kerkini. Places of Ecological and Cultural Interest. Archived August 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 20 ΕΡΩΤΉΣΕΙΣ Οι επενδύσεις στα ιαματικά νερά μηδένισαν την ανεργία στο Άγκιστρο.

- ↑ Μουσείο Ρούπελ Archived May 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. [Museum Rupel. Hellenic Army General Staff.

- ↑ Ruralita Mediterranea. Art, flavours and traditions of the Land of Greece. Archived September 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. p. 13