Adrian Piper

| Adrian Piper | |

|---|---|

Piper in Berlin, 2005 | |

| Born |

September 20, 1948 New York City, New York, United States |

| Residence | Berlin, Germany |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | School of Visual Arts, City College of New York, Harvard University |

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper[1] (born September 20, 1948) is an American conceptual artist and philosopher. Her work addresses ostracism, otherness, racial "passing" and racism. She attended the School of Visual Arts, City College of New York, and Harvard University, where she earned her doctorate in 1981. Piper received visual arts fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1979 and 1982, and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1989. In 1987, she became the first female African-American philosophy professor to receive academic tenure in the United States. In 2012, she received the Artist Award for Distinguished Body of Work from the College Art Association.[2] In 2015, she was awarded the Golden Lion for best artist[3][4] of the 2015 Venice Biennale for her participation in Okwui Enwezor’s central show, “All the World’s Futures”.[5]

Life and career

Adrian Piper was born on September 20, 1948,[6] in New York City.[1][7] She was raised in Manhattan in an upper-middle-class black family, and attended a private school with mostly wealthy, white students.[8] She studied art at the School of Visual Arts[8] and graduated with an associate's degree in 1969.[1] Piper then studied philosophy at the City College of New York[8] and graduated with a bachelor's in 1974.[1] Piper received her master's from Harvard University in 1977 and her doctorate in 1981.[1] She also studied at the University of Heidelberg.[1]

Piper was influenced by Sol LeWitt and Yvonne Rainer in the late 60s and early 70s.[8] She worked at the Seth Siegelaub Gallery, known for its conceptual art exhibitions, in 1969.[8] In 1970, she exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art's Information and began to study philosophy in college.[8] Piper has said that she was kicked out of the art world during this time for her race and gender.[8] Her work started to address ostracism, otherness, and attitudes around racism.[8] In Berger's Critique of Pure Racism interview, Piper asserted that while she finds analysis of racism praiseworthy, she wants her artwork to help people confront their racist views.[8]

Piper was awarded visual arts fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1979 and 1982, and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1989.[1] Piper taught at Wellesley College, Harvard University, Stanford University, University of Michigan, Georgetown University, and University of California, San Diego.[1] She became the first female African-American philosophy professor to receive academic tenure in the United States in 1991.[9] In 2008, for her refusal to return to the United States while listed as a "Suspicious Traveler" on the U.S. Transportation Security Administration Watch List, Wellesley College terminated her tenured full professorship while she was on unpaid leave in Berlin.[10]

In 2011 the American Philosophical Association awarded her the title of Professor Emeritus. In 2013, the Women's Caucus for Art announced that Piper will be a 2014 recipient of the organization's Lifetime Achievement Award.[11]

Piper is divorced and has no children.[1] She currently lives and works in Berlin, where she runs the The Berlin Journal of Philosophy and the Adrian Piper Research Archive. In 2015, she was awarded the Golden Lion for best artist in the international exhibition of the Venice Biennale.[3][4]

Selected works

The first mention of Piper as an artist in the printed press was in the Village Voice on March 27, 1969 in response to what is also considered her first solo exhibition, her mail art project Three Untitled Projects.[12] The people and institutions to whom she sent her 8 1/2 × 11 inch stapled booklets that comprised the piece were listed on the last page as the "Exhibit Locations."[12] With this project, Piper succeeded in distributing her work on her own terms to an audience of over 150 artists, curators and dealers of her choosing.

In the 1970s, Piper began a series of street performances under the collective title Catalysis, which included actions such as painting her clothes with white paint and wearing a sign that read "WET PAINT" and going to the Macy's department store to shop for gloves and sunglasses; stuffing a huge white towel into her mouth and riding the bus, subway and Empire State Building Elevator; and dousing herself in a mixture of vinegar, eggs, milk, and cod liver oil and then spending a week moving around New York's subway and bookstores.[13][14] The Catalysis performances were meant to be a catalyst that challenged what constitutes the order of the social field, "at the level of dress, sanity and the distinction between public and private acts."[13]

Piper's Mythic Being series, started in 1973, saw the artist dress in an afro wig and mustache and perform publicly as a "third world, working class, overly hostile male."[13]

Much of Piper's work deals with issues of passing and racism[15] in the United States. For example, her 1986 work Calling Card, is a card that she could give to call out anyone she perceived to be white who made racist comments in public.[16]

Piper's Everything #5.2 (2004) is a piece of mirrored glass shaped like a tombstone that layers the reflection of the viewer, the text "Everything Will Be Taken Away," and the internal structures behind the plaster of the galley wall. The work can be seen as means of provoking viewers to interrogate the power of institutions to determine the value of a piece of art, as well as to interrogate their own place in the world.[17]

For the piece for which she received top honors at the Venice Biennale in 2015, Piper asked visitors to sign contracts with themselves adhering to one of a trio of posted statements (for instance, one read, "I will always do what I say I am going to do."). In a statement accompanying the award, the jury said: ""Piper has reformed conceptual practice to include personal subjectivity—of herself, her audience, and the publics in general." They also noted that the piece asks its audience "to engage in a lifeling performance of personal responsibility."[18]

- Selected images

-

Alice Down the Rabbit Hole (1965)

-

Hypothesis: Situation #3 (for Sol LeWitt) (1968)

-

Art for the Artworld Surface Pattern (1976)

-

Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features (1981)

-

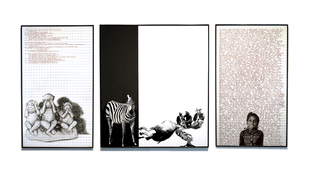

Decide Who You Are, #1: Skinned Alive (1991)

-

What It’s Like, What It Is #3 (1991)

-

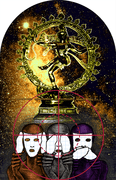

The Color Wheel Series, #29: Annomayakosha (2000)

-

Everything #5.2 (2004–2009)

Reception

Curator Ned Rifkin wrote that Piper "holds a singular position" in the art world.[8] Piper was included in Peggy Phelan and Helena Reckitt's compendium Art and Feminism (2001) where Phelan wrote that her art "worked to show the ways in which racism and sexism are intertwined pathologies which have distorted our lives."[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Farris 1999, p. 314.

- ↑ "2012 Artist Award for Distinguished Body of Work". College Art Association. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- 1 2 "Armenia, Adrian Piper Win Venice Biennale's Golden Lions". ARTnews. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- 1 2 (www.dw.de), Deutsche (May 10, 2015). "Golden Lions for Armenia, Adrian Piper at Venice Biennale". Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Adrian Piper", 56th Venice Biennale.

- ↑ Rifkin 1991, p. 5.

- ↑ Grosenick & Becker 2001, p. 438.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rifkin 1991, p. 1.

- ↑ Vickery & Costello 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ "Adrian Piper's website". Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Women's Caucus for Art". Women's Caucus for Art. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- 1 2 Anastas, Rhea, ed. (2006). Witness to Her Art. Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. pp. 75–76.

- 1 2 3 4 Phelan, Peggy (2001). Survey. London: Phaidon. ISBN 9780714863917.

- ↑ Buskirk, Martha (2003). The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. p. 213.

- ↑ Bowles, John Parish (2011-01-01). Adrian Piper: Race, Gender, and Embodiment. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822348962.

- ↑ Jones, Amelia (January 1, 2012). Seeing differently: a history and theory identification and the visual arts. ISBN 9780415543828.

- ↑ Borggreen, Gunhild; Gade, Rune (2013). Performing Archives/Archives of Performance. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788763537506.

- ↑ "Armenia, Adrian Piper Win Venice Biennale's Golden Lions". ARTnews. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

Sources

- Farris, Phoebe, ed. (1999). Women Artists of Color: A Bio-critical Sourcebook to 20th Century Artists in the Americas. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 314–319. ISBN 978-0-313-30374-6.

- Grosenick, Uta; Becker, Ilka, eds. (2001). Women Artists in the 20th and 21st Century. Taschen. pp. 438–443. ISBN 978-3-8228-5854-7.

- Phelan, Peggy (2001). Art and Feminism. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-714-86391-7.

- Piper, Adrian (1996). Out of Order, Out of Sight: Volume 1: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992]. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 0262661527.

- Piper, Adrian (1996). Out of Order, Out of Sight: Volume II: Selected Writings in Art Criticism 1967-1992]. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 0262661535.

- Rifkin, Ned (1991). Directions: Adrian Piper "What It's Like, What It Is #2", June 19 – September 22, 1991. New York.

- Vickery, Jonathan; Costello, Diarmuid, eds. (2007). Art: Key Contemporary Thinkers. Berg. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-0-85785-077-5.

External links

![]() Media related to Adrian Piper at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adrian Piper at Wikimedia Commons