Acute kidney injury

| Acute kidney injury | |

|---|---|

|

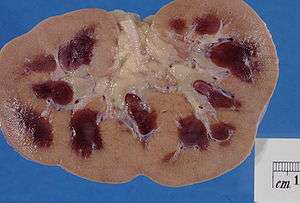

Pathologic kidney specimen showing marked pallor of the cortex, contrasting to the darker areas of surviving medullary tissue. The patient died with acute kidney injury. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| ICD-10 | N17 |

| ICD-9-CM | 584 |

| DiseasesDB | 11263 |

| MedlinePlus | 000501 |

| eMedicine | med/1595 |

| Patient UK | Acute kidney injury |

| MeSH | D058186 |

Acute kidney injury (AKI), previously called acute renal failure (ARF),[1][2] is an abrupt loss of kidney function that develops within 7 days.[3]

Its causes are numerous. Generally it occurs because of damage to the kidney tissue caused by decreased kidney blood flow (kidney ischemia) from any cause (e.g., low blood pressure), exposure to substances harmful to the kidney, an inflammatory process in the kidney, or an obstruction of the urinary tract that impedes the flow of urine. AKI is diagnosed on the basis of characteristic laboratory findings, such as elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine, or inability of the kidneys to produce sufficient amounts of urine.

AKI may lead to a number of complications, including metabolic acidosis, high potassium levels, uremia, changes in body fluid balance, and effects on other organ systems, including death. People who have experienced AKI may have an increased risk of chronic kidney disease in the future. Management includes treatment of the underlying cause and supportive care, such as renal replacement therapy.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical picture is often dominated by the underlying cause, e.g. postoperative state. The symptoms of acute kidney injury result from the various disturbances of kidney function that are associated with the disease. Accumulation of urea and other nitrogen-containing substances in the bloodstream lead to a number of symptoms, such as fatigue, loss of appetite, headache, nausea and vomiting.[4] Marked increases in the potassium level can lead to abnormal heart rhythms, which can be severe and life-threatening.[5] Fluid balance is frequently affected, though blood pressure can be high, low or normal.[6]

Pain in the flanks may be encountered in some conditions (such as clotting of the kidneys' blood vessels or inflammation of the kidney); this is the result of stretching of the fibrous tissue capsule surrounding the kidney.[7] If the kidney injury is the result of dehydration, there may be thirst as well as evidence of fluid depletion on physical examination.[7] Physical examination may also provide other clues as to the underlying cause of the kidney problem, such as a rash in interstitial nephritis (or vasculitis) and a palpable bladder in obstructive nephropathy.[7]

Causes

Classification

Acute kidney injury is diagnosed on the basis of clinical history and laboratory data. A diagnosis is made when there is a rapid reduction in kidney function, as measured by serum creatinine, or based on a rapid reduction in urine output, termed oliguria (less than 400 mLs of urine per 24 hours).

| Type | UOsm | UNa | FeNa | BUN/Cr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prerenal | >500 | <10 | <1% | >20 |

| Intrinsic | <350 | >20 | >2% | <15 |

| Postrenal | <350 | >40 | >4% | >15 |

AKI can be caused by systemic disease (such as a manifestation of an autoimmune disease, e.g. lupus nephritis), crush injury, contrast agents, some antibiotics, and more. AKI often occurs due to multiple processes. The most common cause is dehydration and sepsis combined with nephrotoxic drugs, especially following surgery or contrast agents.

The causes of acute kidney injury are commonly categorized into prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal.

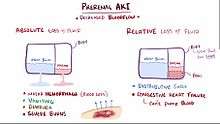

Prerenal

Prerenal causes of AKI ("pre-renal azotemia") are those that decrease effective blood flow to the kidney and cause a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Both kidneys need to be affected as one kidney is still more than adequate for normal kidney function. Notable causes of prerenal AKI include low blood volume (e.g., dehydration), low blood pressure, heart failure (leading to cardiorenal syndrome), liver cirrhosis and local changes to the blood vessels supplying the kidney. The latter include renal artery stenosis, or the narrowing of the renal artery which supplies the kidney with blood, and renal vein thrombosis, which is the formation of a blood clot in the renal vein that drains blood from the kidney.

Intrinsic

Intrinsic AKI refers to disease processes which directly damage the kidney itself. Intrinsic AKI can be due to one or more of the kidney's structures including the glomeruli, kidney tubules, or the interstitium. Common causes of each are glomerulonephritis, acute tubular necrosis (ATN), and acute interstitial nephritis (AIN), respectively. Other causes of intrinsic AKI are rhabdomyolysis and tumor lysis syndrome.[8]

Postrenal

Postrenal AKI refers to acute kidney injury caused by disease states downstream of the kidney and most often occurs as a consequence of urinary tract obstruction. This may be related to benign prostatic hyperplasia, kidney stones, obstructed urinary catheter, bladder stones, or cancer of the bladder, ureters, or prostate.

Diagnosis

Definition

Introduced by the KDIGO in 2012,[9] specific criteria exist for the diagnosis of AKI.

AKI can be diagnosed if any one of the following is present:

- Increase in SCr by ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 μmol/l) within 48 hours; or

- Increase in SCr to ≥1.5 times baseline, which has occurred within the prior 7 days; or

- Urine volume < 0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 hours.

Staging

The RIFLE criteria, proposed by the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) group, aid in assessment of the severity of a person's acute kidney injury. The acronym RIFLE is used to define the spectrum of progressive kidney injury seen in AKI:[10][11]

- Risk: 1.5-fold increase in the serum creatinine, or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decrease by 25 percent, or urine output <0.5 mL/kg per hour for six hours.

- Injury: Two-fold increase in the serum creatinine, or GFR decrease by 50 percent, or urine output <0.5 mL/kg per hour for 12 hours

- Failure: Three-fold increase in the serum creatinine, or GFR decrease by 75 percent, or urine output of <0.3 mL/kg per hour for 24 hours, or no urine output (anuria) for 12 hours

- Loss: Complete loss of kidney function (e.g., need for renal replacement therapy) for more than four weeks

- End-stage kidney disease: Complete loss of kidney function (e.g., need for renal replacement therapy) for more than three months

Evaluation

The deterioration of kidney function may be signaled by a measurable decrease in urine output. Often, it is diagnosed on the basis of blood tests for substances normally eliminated by the kidney: urea and creatinine. Additionally, the ratio of BUN to creatinine is used as a Both tests have their disadvantages. For instance, it takes about 24 hours for the creatinine level to rise, even if both kidneys have ceased to function. A number of alternative markers has been proposed (such as NGAL, KIM-1, IL18 and cystatin C), but none of them is currently established enough to replace creatinine as a marker of kidney function.[12]

Once the diagnosis of AKI is made, further testing is often required to determine the underlying cause. It is useful to perform a bladder scan or a post void residual to rule out urinary retention. In post void residual, a catheter is inserted into the urinary tract immediately after urinating to measure fluid still in the bladder. 50–100 ml suggests neurogenic bladder dysfunction. A kidney ultrasound will demonstrate hydronephrosis if present. A CT scan of the abdomen will also demonstrate bladder distension or hydronephrosis. However, in AKI, the use of IV contrast is contraindicated as the contrast agent used is nephrotoxic.

These may include urine sediment analysis, kidney ultrasound and/or kidney biopsy. Indications for kidney biopsy in the setting of AKI include the following:[13]

- Unexplained AKI, in a patient with two non-obstructed normal sized kidneys

- AKI in the presence of the nephritic syndrome

- Systemic disease associated with AKI

- Kidney transplant dysfunction

Treatment

The management of AKI hinges on identification and treatment of the underlying cause. The main objectives of initial management are to prevent cardiovascular collapse and death and to call for specialist advice from a nephrologist. In addition to treatment of the underlying disorder, management of AKI routinely includes the avoidance of substances that are toxic to the kidneys, called nephrotoxins. These include NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or naproxen, iodinated contrasts such as those used for CT scans, many antibiotics such as gentamicin, and a range of other substances.[14]

Monitoring of kidney function, by serial serum creatinine measurements and monitoring of urine output, is routinely performed. In the hospital, insertion of a urinary catheter helps monitor urine output and relieves possible bladder outlet obstruction, such as with an enlarged prostate.

Specific therapies

In prerenal AKI without fluid overload, administration of intravenous fluids is typically the first step to improving kidney function. Volume status may be monitored with the use of a central venous catheter to avoid over- or under-replacement of fluid.

If low blood pressure persists despite providing a person with adequate amounts of intravenous fluid, medications that increase blood pressure (vasopressors) such as norepinephrine and in certain circumstances medications that improve the heart's ability to pump (known as inotropes) such as dobutamine may be given to improve blood flow to the kidney. While a useful vasopressor, there is no evidence to suggest that dopamine is of any specific benefit and may be harmful.[15]

The myriad causes of intrinsic AKI require specific therapies. For example, intrinsic AKI due to vasculitis or glomerulonephritis may respond to steroid medication, cyclophosphamide, and (in some cases) plasma exchange. Toxin-induced prerenal AKI often responds to discontinuation of the offending agent, such as ACE inhibitors, ARB antagonists, aminoglycosides, penicillins, NSAIDs, or paracetamol.[7]

If the cause is obstruction of the urinary tract, relief of the obstruction (with a nephrostomy or urinary catheter) may be necessary.

Diuretic agents

The use of diuretics such as furosemide, is widespread and sometimes convenient in ameliorating fluid overload. It is not associated with higher mortality (risk of death),[16] nor with any reduced mortality or length of intensive care unit or hospital stay.[17]

Renal replacement therapy

Renal replacement therapy, such as with hemodialysis, may be instituted in some cases of AKI. Renal replacement therapy can be applied intermittently (IRRT) and continuously (CRRT). Study results regarding differences in outcomes between IRRT and CRRT are inconsistent. A systematic review of the literature in 2008 demonstrated no difference in outcomes between the use of intermittent hemodialysis and continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH) (a type of continuous hemodialysis).[18] Among critically ill patients, intensive renal replacement therapy with CVVH does not appear to improve outcomes compared to less intensive intermittent hemodialysis.[14][19] However, other studies demonstrated that compared with IRRT, initiation of CRRT is associated with a lower likelihood of chronic dialysis.[20][21]

Complications

Metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, and pulmonary edema may require medical treatment with sodium bicarbonate, antihyperkalemic measures, and diuretics.

Lack of improvement with fluid resuscitation, therapy-resistant hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, or fluid overload may necessitate artificial support in the form of dialysis or hemofiltration.[5]

Prognosis

Mortality

Mortality after AKI remains high. Overall it is 20%; 30% if the patient is referred to nephrology, 50% if dialyzed, and 70% if on ICU.

If AKI develops after major surgery (13.4% of all people who have undergone major surgery) the risk of death is markedly increased (over 12-fold).[22]

Kidney function

Depending on the cause, a proportion of patients (5–10%) will never regain full kidney function, thus entering end-stage kidney failure and requiring lifelong dialysis or a kidney transplant. Patients with AKI are more likely to die prematurely after being discharged from hospital, even if their kidney function has recovered.[2]

The risk of developing chronic kidney disease is increased (8.8-fold).[23]

Epidemiology

New cases of AKI are unusual but not rare, affecting approximately 0.1% of the UK population per year (2000 ppm/year), 20x incidence of new ESKD. AKI requiring dialysis (10% of these) is rare (200 ppm/year), 2x incidence of new ESKD.[24]

There is an increased incidence of AKI in agricultural workers, particularly those paid by the piece. No other traditional risk factors, including age, BMI, diabetes, or hypertension, were associated with incident AKI. Agricultural workers are at increased risk for AKI because of occupational hazards such as dehydration and heat illness.[25]

Acute kidney injury is common among hospitalized patients. It affects some 3–7% of patients admitted to the hospital and approximately 25–30% of patients in the intensive care unit.[26]

Acute kidney injury was one of the most expensive conditions seen in U.S. hospitals in 2011, with an aggregated cost of nearly $4.7 billion for approximately 498,000 hospital stays.[27] This was a 346% increase in hospitalizations from 1997, when there were 98,000 acute kidney injury stays.[28] According to a review article of 2015, there has been an increase in cases of acute kidney injury in the last 20 years which cannot be explained solely by changes to the manner of reporting.[29]

History

Before the advancement of modern medicine, acute kidney injury was referred to as uremic poisoning while uremia was contamination of the blood with urine. Starting around 1847, uremia came to be used for reduced urine output, a condition now called oliguria, which was thought to be caused by the urine's mixing with the blood instead of being voided through the urethra.

Acute kidney injury due to acute tubular necrosis (ATN) was recognized in the 1940s in the United Kingdom, where crush injury victims during the London Blitz developed patchy necrosis of kidney tubules, leading to a sudden decrease in kidney function.[30] During the Korean and Vietnam wars, the incidence of AKI decreased due to better acute management and administration of intravenous fluids.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ Webb S, Dobb G (December 2007). "ARF, ATN or AKI? It's now acute kidney injury". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 35 (6): 843–4. PMID 18084974.

- 1 2 Dan Longo; Anthony Fauci; Dennis Kasper; Stephen Hauser; J. Jameson; Joseph Loscalzo (July 21, 2011). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 18 edition. McGraw-Hill Professional.

- ↑ Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A (2007). "Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury". Critical Care (London, England). 11 (2): R31. doi:10.1186/cc5713. PMC 2206446

. PMID 17331245.

. PMID 17331245. - ↑ Skorecki K, Green J, Brenner BM (2005). "Chronic renal failure". In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1653–63. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

- 1 2 Weisberg LS (December 2008). "Management of severe hyperkalemia". Crit. Care Med. 36 (12): 3246–51. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f222b. PMID 18936701.

- ↑ Tierney, Lawrence M.; Stephen J. McPhee; Maxine A. Papadakis (2004). "22". CURRENT Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2005 (44th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 871. ISBN 0-07-143692-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Brady HR, Brenner BM (2005). "Chronic renal failure". In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1644–53. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

- ↑ Jim Cassidy; Donald Bissett; Roy A. J. Spence; Miranda Payne (1 January 2010). Oxford Handbook of Oncology. Oxford University Press. p. 706. ISBN 978-0-19-956313-5.

- ↑ Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney inter.

- ↑ Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P (2004). "Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group". Crit Care. 8 (4): R204–12. doi:10.1186/cc2872. PMC 522841

. PMID 15312219.

. PMID 15312219. - ↑ Lameire N, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R (2005). "Acute renal failure". Lancet. 365 (9457): 417–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17831-3. PMID 15680458.

- ↑ Chawla LS, Kellum JA (Jan 17, 2012). "Acute kidney injury in 2011: Biomarkers are transforming our understanding of AKI.". Nature Reviews Nephrology. 8 (2): 68–70. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2011.216. PMID 22249777.

- ↑ Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ (2008). Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-159124-9.

- 1 2 Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, O'Connor TZ, Chertow GM, Crowley ST, Choudhury D, Finkel K, Kellum JA, Paganini E, Schein RM, Smith MW, Swanson KM, Thompson BT, Vijayan A, Watnick S, Star RA, Peduzzi P (July 2008). "Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802639. PMC 2574780

. PMID 18492867.

. PMID 18492867. - ↑ Holmes CL, Walley KR (2003). "Bad medicine: low-dose dopamine in the ICU". Chest. 123 (4): 1266–75. doi:10.1378/chest.123.4.1266. PMID 12684320.

- ↑ Uchino S, Doig GS, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Nacedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C, Kellum JA (2004). "Diuretics and mortality in acute renal failure". Crit. Care Med. 32 (8): 1669–77. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000132892.51063.2F. PMID 15286542.

- ↑ Davis A, Gooch I (2006). "The use of loop diuretics in acute renal failure in critically ill patients to reduce mortality, maintain renal function, or avoid the requirements for renal support". Emergency Medicine Journal. 23 (7): 569–70. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.038513. PMC 2579558

. PMID 16794108.

. PMID 16794108. - ↑ Pannu N, Klarenbach S, Wiebe N, Manns B, Tonelli M (February 2008). "Renal replacement therapy in patients with acute renal failure: a systematic review". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 299 (7): 793–805. doi:10.1001/jama.299.7.793. PMID 18285591.

- ↑ Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, Lo S, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Myburgh J, Norton R, Scheinkestel C, Su S (October 2009). "Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (17): 1627–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0902413. PMID 19846848.

- ↑ Schoenfelder, T; Chen, X; Bless, HH (April 2016). "Health Technology Assessment: Continuous renal replacement therapy versus intermittent renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury in adult patients" (PDF). Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information. DAHTA658 (HTAI010). Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Schneider, AG; Bellomo, R; Bagshaw, SM; Glassford, NJ; Lo, S; Jun, M; Cass, A; Gallagher, M (June 2013). "Choice of renal replacement therapy modality and dialysis dependence after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". Intensive care medicine. 39 (6): 987–997. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2864-5. PMID 23443311.

- ↑ O'Connor, M. E.; Kirwan, C. J.; Pearse, R. M.; Prowle, J. R. (24 November 2015). "Incidence and associations of acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (4): 521–530. doi:10.1007/s00134-015-4157-7. PMID 26602784.

- ↑ Coca, SG; Singanamala, S; Parikh, CR (March 2012). "Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". Kidney International. 81 (5): 442–8. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.379. PMC 3788581

. PMID 22113526.

. PMID 22113526. - ↑ "Renal Medicine: Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)". Renalmed.co.uk. 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ↑ Moyce, Sally, RN, BSN; Joseph, Jill, MD, PhD; Tancredi, Daniel, PhD; Mitchell, Diane, PhD; Schenker, Marc, MD, MPH (2016) "Cumulative Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury in California's Agricultural Workers" Journal of Environmental Medicine JOEM 58 Number 4, April 2016 391-397

- ↑ Brenner and Rector's The Kidney. Philadelphia: Saunders. 2007. ISBN 1-4160-3110-3.

- ↑ Torio CM, Andrews RM. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. August 2013.

- ↑ Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Stocks C. Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #162. September 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

- ↑ Siew ED, Davenport A (2015). "The growth of acute kidney injury: a rising tide or just closer attention to detail?". Kidney International (Review). 87 (1): 46–61. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.293. PMC 4281297

. PMID 25229340.

. PMID 25229340. - ↑ Bywaters EG, Beall D (1941). "Crush injuries with impairment of renal function.". Br Med J. 1 (4185): 427–32. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4185.427. PMC 2161734

. PMID 20783577.

. PMID 20783577. - ↑ Schrier RW, Wang W, Poole B, Mitra A (2004). "Acute renal failure: definitions, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy". J. Clin. Invest. 114 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1172/JCI22353. PMC 437979

. PMID 15232604.

. PMID 15232604.