Achilles Gasser

Achilles Pirmin Gasser[1] (3 November 1505 – 4 December 1577) was a German physician and astrologer. He is now known as a well-connected humanist scholar, and supporter of both Copernicus and Rheticus.

Life

Born in Lindau, he studied mathematics, history and philosophy as well as astronomy.[2] He was a student in Sélestat under Johannes Sapidus;[3] he also attended universities in Wittenberg, Vienna, Montpellier, and Avignon.[4]

Rheticus lost his physician father Georg Iserin in 1528, executed on sorcery charges. Gasser later took over the practice in Feldkirch, in 1538; he taught Rheticus some astrology, and helped his education, in particular by writing to the University of Wittenberg on his behalf.[4][5][6]

When Rheticus printed his Narratio prima—the first published account of the Copernican heliocentric system—in 1540 (Danzig), he sent Gasser a copy. Gasser then undertook a second edition (1541, Basel) with his own introduction,[7] in the form of a letter from Gasser to Georg Vogelin of Konstanz.[4] The second edition (1566, Basel) of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium contained the Narratio Prima with this introduction by Gasser.[8]

Gasser died in Augsburg.

Works

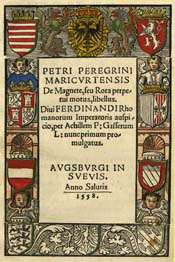

He prepared the first edition (Augsburg, 1558) of the Epistola de magnete of Pierre de Maricourt.[2][9]

Other works include:

- Comet observations[10]

- Historiarum et Chronicorum totius mundi epitome (1538)

- Prognosticon (1544) dedicated to Thomas Venatorius[11]

- Edition of the Evangelienbuch of Otfried of Weissenburg. His edition did not appear until 1571, under the name of Matthias Flacius who had taken over.[12]

Gasser belonged with Flacius to the humanist circle around Kaspar von Niedbruck, concerned with the recovery of monastic manuscripts. Others in the group were John Bale, Conrad Gesner, Joris Cassander, Johannes Matalius Metellus, and Cornelius Wauters.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Also Gassar, Gasserus, Gassarus.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ↑ Peter G. Bietenholz and Thomas Brian Deutscher, Contemporaries of Erasmus: a biographical register of the Renaissance and Reformation (2003), Volume 3, p. 196; Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Danielson, Dennis (2004), "Achilles Gasser and the birth of Copernicanism", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 35 Part 4 (121): 457–474, ISSN 0021-8286.

- ↑ MacTutor page on Rheticus

- ↑ Repcheck, pp. 113–4.

- ↑ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/copernicus/

- ↑ http://copernicus.torun.pl/en/archives/De_revolutionibus/3/

- ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pierre de Maricourt". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pierre de Maricourt". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Kokott, W., The Comet of 1533, p. 105.

- ↑ Anthony Grafton, Cardano's Cosmos: the worlds and works of a Renaissance astrologer (1999), p. 56; Google Books

- ↑ Dictionaries in Early Modern Europe (PDF), p. 122.

- ↑ Kees Dekker and Cornelis Dekker, The Origins of Old Germanic Studies in the Low Countries (1999), p. 21; Google Books.

References

- Jack Repcheck (2007), Copernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution Began

Further reading

- Karl Heinz Burmeister (1970), Achilles Pirmin Gasser, 1505-1577. Arzt u. Naturforscher, Historiker und Humanist. (3 volumes.)

- Karl Heinz Burmeister, Achilles Pirmin Gasser (1505-1577) as Geographer and Cartographer, Imago Mundi Vol. 24, (1970), pp. 57–62; http://www.jstor.org/stable/1150458

External links

- (German) de:s:ADB:Gasser, Achilles Pirminius, NDB

- CERL page

- (French) Old dictionary entry