2007–08 world food price crisis

World food prices increased dramatically in 2007 and the first and second quarter of 2008,[1] creating a global crisis and causing political and economic instability and social unrest in both poor and developed nations. Although the media spotlight focused on the riots that ensued in the face of high prices, the ongoing crisis of food insecurity has been years in the making.[2][3] Systemic causes for the worldwide increases in food prices continue to be the subject of debate. After peaking in the second quarter of 2008, prices fell dramatically during the late-2000s recession but increased during 2009 and 2010, peaking again in early 2011 at a level slightly higher than the level reached in 2008.[1][4] However a repeat of the crisis of 2008 is not anticipated due to ample stockpiles.[5]

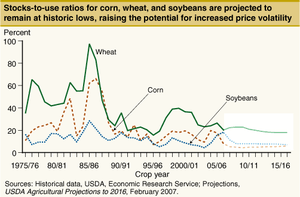

The initial causes of the late-2006 price spikes included droughts in grain-producing nations and rising oil prices.[6] Oil price increases also caused general escalations in the costs of fertilizers, food transportation, and industrial agriculture. Root causes may be the increasing use of biofuels in developed countries (see also food vs fuel),[7] and an increasing demand for a more varied diet across the expanding middle-class populations of Asia.[8][9] The Food and Agriculture Organization also raised concerns about the role of hedge funds speculating on prices leading to major shifts in prices.[10] These factors, coupled with falling world-food stockpiles, all contributed to the worldwide rise in food prices.[11]

Drastic price increases

Between 2006 and 2008 average world prices for rice rose by 217%, wheat by 136%, corn by 125% and soybeans by 107%. In late April 2008 rice prices hit 24 cents (US) per US pound, more than doubling the price in just seven months.[13]

World population growth

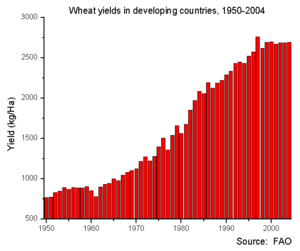

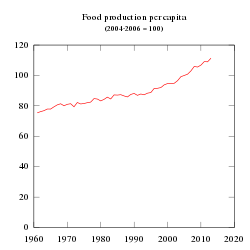

Although some commentators have argued that this food crisis stems from unprecedented global population growth,[14][15] others point out that world population growth rates have dropped dramatically since the 1980s,[16][17] and grain availability has continued to outpace population.

To prevent price growth, food production should outpace population growth, which was about 1.2% per year. But there was a temporary drop in food production growth:[18][19] for example, wheat production during 2006 and 2007 was 4% lower than that in 2004 and 2005.

World population has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to over 7.2 billion today.[20][21]

Increased demand for more resource intensive food

The head of the International Food Policy Research Institute, stated in 2008 that the gradual change in diet among newly prosperous populations is the most important factor underpinning the rise in global food prices.[22] Where food consumption has increased, it has largely been in processed ("value added") foods, sold in developing and developed nations.[23] Total grain utilization growth since 2006 (up three percent, over the 2000–2006 per annum average of two percent) has been greatest in non-food usage, especially in feed and biofuels.[24][25]

One kilogram of beef requires seven kilograms of feed grain.[26] These reports, therefore, conclude that usage in industrial, feed, and input intensive foods, not population growth among poor consumers of simple grains, has contributed to the price increases. Rising meat consumption due to changes in lifestyle can in turn lead to higher energy consumption due to the higher energy-intensity of meat products, for example, one kilogram of meat uses about 19 times as much energy to produce it as the same amount of apple.[27]

| India | China | Brazil | Nigeria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Meat | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| Milk | 1.2 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Fish | 1.2 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Fruits | 1.3 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Vegetables | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

Although the vast majority of the population in Asia remains rural and poor, the growth of the middle class in the region has been dramatic. For comparison, in 1990, the middle class grew by 9.7 percent in India and 8.6 percent in China, but by 2007 the growth rate was nearly 30 percent and 70 percent respectively.[11] The corresponding increase in Asian affluence also brought with it a change in lifestyle and eating habits, particularly a demand for greater variety, leading to increased competition with western nations for already strained agricultural resources.[8][29] This demand exacerbates dramatic increases in commodity prices such as oil.

Another issue with rising affluence in India and China was reducing the "shock absorber" of poor people who are forced to reduce their resource consumption when food prices rise. This reduced price elasticity and caused a sharp rise in food prices during some shortages. In the media, China is often mentioned as one of the main reasons for the increase in world food prices. However, China has to a large extent been able to meet its own demand for food, and even exports its surpluses in the world market.[30]

Effects of petroleum and fertilizer price increases

Starting in 2007, the prices of fertilizers of all kinds increased dramatically, peaking around the summer of 2008 (see graphs by the International Fertilizer Industry Association). Prices approximately tripled for ammonia, urea, diammonium phosphate, muriate of potash (KCl), and sulfuric acid (used for making phosphate fertilizer), and then fell just as dramatically in the latter part of 2008. Some prices doubled within the six months before April 2008.[31] Part of the cause for these price rises was the rise in the price of oil, since the most fertilizers require petroleum or natural gas to manufacture.[11] Although the main fossil fuel input for fertilizer comes from natural gas to generate hydrogen for the Haber–Bosch process (see: Ammonia production), natural gas has its own supply problems similar to those for oil. Because natural gas can substitute for petroleum in some uses (for example, natural gas liquids and electricity generation), increasing prices for petroleum lead to increasing prices for natural gas, and thus for fertilizer.

Costs for fertilizer raw materials other than oil, such as potash, have been increasing[32] as increased production of staples increases demand. This is causing a boom (with associated volatility) in agriculture stocks.

The major IFPRI Report launched in February 2011 stated that the causes of the 2008 global food crisis were similar to that of the 1972–74 food crisis, in that the oil price and energy price was the major driver, as well as the shock to cereal demand (from biofuels this time), low interest rates, devaluation of the dollar, declining stocks, and some adverse weather conditions.[33] Unfortunately the IFPRI states that such shocks are likely to recur with several shocks in the future; compounded by a long history of neglecting agricultural investments.

Declining world food stockpiles

In the past, nations tended to keep more sizable food stockpiles, but more recently, due to a faster pace of food growth and ease of importation, less emphasis is placed on high stockpiles. For example, in February 2008 wheat stockpiles hit a 60-year low in the United States (see also Rice shortage).[11] Data stocks are often calculated as a residual between Production and Consumption but it becomes difficult to discriminate between a de-stocking policy choices of individual countries and a deficit between production and consumption.

Financial speculation

Destabilizing influences, including indiscriminate lending and real estate speculation, led to a crisis in January 2008, and eroded investment in food commodities.[11]

Foreign investment drives productivity improvements, and other gains for farmers.[34][35][36]

Commodity index funds

Goldman Sachs' entry into the commodities market via the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index has been implicated by some in the 2007–2008 world food price crisis. In a 2010 article in Harper's magazine, Frederick Kaufman magazine accused Goldman Sachs of profiting while many people went hungry or even starved. He argued that Goldman's large purchases of long-options on wheat futures created a demand shock in the wheat market, which disturbed the normal relationship between supply and demand and price levels. He argues that the result was a 'contango' wheat market on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which caused prices of wheat to rise much higher than normal, defeating the purpose of the exchanges (price stabilization) in the first place.[37][38][39] however, a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – using data from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission – showed tracking funds (of which Goldman Sachs Commodity Index was one) did not cause the bubble. For example, the report points out that even commodities without futures markets also saw price rises during the period.[40] Some commodities without futures markets saw their prices rise as a consequence of the rising prices of commodities with futures markets: the World Development Movement states there is strong evidence that the rising price of wheat caused the price of rice to subsequently rise as well.[41]

Effects of trade liberalization

Some theorists, such as Martin Khor of the Third World Network,[42] point out that many developing nations have gone from being food independent to being net food importing economies since the 1970s and 1980s International Monetary Fund (and later the World Trade Organisation's Agreement on Agriculture) free market economics directives to debtor nations. In opening developing countries to developed world food imports subsidised by Western governments, developing nations can become more dependent upon food imports if local agriculture does not improve.[42][43]

While developed countries pressured the developing world to abolish subsidies in the interest of trade liberalization, rich countries largely kept subsidies in place for their own farmers. In recent years United States government subsidies have been added to push production toward biofuel rather than food and vegetables .[11]

Effects of food for fuel

One systemic cause for the price rise is held to be the diversion of food crops (maize in particular) for making first-generation biofuels.[44] An estimated 100 million tons of grain per year are being redirected from food to fuel.[45] (Total worldwide grain production for 2007 was just over 2000 million tons.[46]) As farmers devoted larger parts of their crops to fuel production than in previous years, land and resources available for food production were reduced correspondingly.

This has resulted in less food available for human consumption, especially in developing and least developed countries, where a family's daily allowances for food purchases are extremely limited. The crisis can be seen, in a sense, to dichotomize rich and poor nations, since, for example, filling a tank of an average car with biofuel, amounts to as much maize (Africa's principal food staple) as an African person consumes in an entire year.[11]

Brazil, the world's second largest producer of ethanol after the US, is considered to have the world's first sustainable biofuels economy[47][48][49] and its government claims Brazil's sugar cane based ethanol industry has not contributed to the 2008 food crises.[49][50] A World Bank policy research working paper released in July 2008[51] concluded that "...large increases in biofuels production in the United States and Europe are the main reason behind the steep rise in global food prices", and also stated that "Brazil's sugar-based ethanol did not push food prices appreciably higher".[52][53] An economic assessment published in July 2008 by the OECD[54] disagrees with the World Bank report regarding the negative effects of subsidies and trade restrictions, finding that the effect of biofuels on food prices are much smaller.[55]

A report released by Oxfam in June 2008[56] criticized biofuel policies of rich countries and concluded that, of all biofuels available in the market, Brazilian sugarcane ethanol is "far from perfect" but it is the most favorable biofuel in the world in term of cost and GHG balance. The report discusses some existing problems and potential risks and asks the Brazilian government for caution to avoid jeopardizing its environmental and social sustainability. The report also says that: "Rich countries spent up to $15 billion last year supporting biofuels while blocking cheaper Brazilian ethanol, which is far less damaging for global food security."[57][58] (See Ethanol fuel in Brazil)

German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the rise in food prices is due to poor agricultural policies and changing eating habits in developing nations, not biofuels as some critics claim.[59] On 29 April 2008, US President George W. Bush declared during a press conference that "85 percent of the world's food prices are caused by weather, increased demand and energy prices", and recognized that "15 percent has been caused by ethanol".[60] On 4 July 2008, The Guardian reported that a leaked World Bank report estimated the rise in food prices caused by biofuels to be 75%.[61] This report was officially released in July 2008.[51]

Since reaching record high prices in June 2008, corn prices fell 50% by October 2008, declining sharply together with other commodities, including oil. As ethanol production from corn has continued at the same levels, some have argued this trend shows the belief that the increased demand for corn to produce ethanol was mistaken. "Analysts, including some in the ethanol sector, say ethanol demand adds about 75 cents to $1.00 per bushel to the price of corn, as a rule of thumb. Other analysts say it adds around 20 percent, or just under 80 cents per bushel at current prices. Those estimates hint that $4 per bushel corn might be priced at only $3 without demand for ethanol fuel."[62] These industry sources consider that a speculative bubble in the commodity markets holding positions in corn futures was the main driver behind the observed hike in corn prices affecting food supply.

Second- and third-generation biofuels (such as cellulosic ethanol and algae fuel, respectively) may someday ease the competition with food crops, as can grow on marginal lands unsuited for food crops, but these advanced biofuels require further development of farming practices and refining technology; in contrast, ethanol from maize uses mature technology and the maize crop can be shifted between food and fuel use quickly.

Biofuel subsidies in the US and the EU

The World Bank lists the effect of biofuels as an important contributor to higher food prices.[63] The FAO/ECMB has reported that world land usage for agriculture has declined since the 1980s, and subsidies outside the United States and EU have dropped since the year 2004, leaving supply, while sufficient to meet 2004 needs, vulnerable when the United States began converting agricultural commodities to biofuels.[64] According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), global wheat imports and stocks have decreased, domestic consumption has stagnated, and world wheat production has decreased from 2006 to 2008.[65]

In the United States, government subsidies for ethanol production have prompted many farmers to switch to production for biofuel. Maize is the primary crop used for the production of ethanol, with the United States being the biggest producer of maize ethanol. As a result, 23 percent of United States maize crops were being used for ethanol in 2006–2007 (up from 6 percent in 2005–2006), and the USDA expects the United States to use 81 million tons of maize for ethanol production in the 2007–2008 season, up 37 percent.[66] This not only diverts grains from food, but it diverts agricultural land from food production.

Nevertheless, supporters of ethanol claim that using corn for ethanol is not responsible for the worst food riots in the world, many of which have been caused by the price of rice and oil, which are not affected by biofuel use but rather by supply and demand.

However, a World Bank policy research working paper released in July 2008[51] says that biofuels have raised food prices between 70 and 75 percent. The study found that higher oil prices and a weak dollar explain 25–30% of total price rise. The "month-by-month" five-year analysis disputes that increases in global grain consumption and droughts were responsible for price increases, reporting that this had had only a marginal effect and instead argues that the EU and US drive for biofuels has had by far the biggest effect on food supply and prices. The paper concludes that increased production of biofuels in the US and EU were supported by subsidies and tariffs on imports, and considers that without these policies, price increases would have been smaller. This research also concluded that Brazil's sugar cane based ethanol has not raised sugar prices significantly, and suggest to remove tariffs on ethanol imports by both the US and EU, to allow more efficient producers such as Brazil and other developing countries to produce ethanol profitably for export to meet the mandates in the EU and the US.[52][53]

The Renewable Fuel Association (RFA) published a rebuttal based on the version leaked before the formal release of the World Bank's paper.[67] The RFA critique considers that the analysis is highly subjective and that the author "estimates the effect of global food prices from the weak dollar and the direct and indirect effect of high petroleum prices and attributes everything else to biofuels."[68]

An economic assessment report also published in July 2008 by the OECD[54] agrees with the World Bank report regarding the negative effects of subsidies and trade restrictions, but found that the effect of biofuels on food prices are much smaller. The OECD study is also critical of the limited reduction of GHG emissions achieved from biofuels produced in Europe and North America, concluding that the current biofuel support policies would reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transport fuel by no more than 0.8 percent by 2015, while Brazilian ethanol from sugar cane reduces greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80 percent compared to fossil fuels. The assessment calls on governments for more open markets in biofuels and feedstocks to improve efficiency and lower costs.[55]

Idled farmland

According to the New York Times on 9 April 2008, the United States government pays farmers to idle their cropland under a conservation program. This policy reached a peak of 36,800,000 acres (149,000 km2) idled in 2007, that is 8% of cropland in United States, representing a total area bigger than the state of New York.[69]

Agricultural subsidies

The global food crisis has renewed calls for removal of distorting agricultural subsidies in developed countries.[70] Support to farmers in OECD countries totals 280 billion USD annually, which compares to official development assistance of just 80 billion USD in 2004, and farm support depresses global food prices, according to OECD estimates.[71] These agricultural subsidies lead to underdevelopment in rural developing countries, including the least developed countries; meanwhile subsidised food increases overconsumption in developed countries. The US Farm Bill brought in by the Bush Administration in 2002 increased agricultural subsidies by 80% and cost the US taxpayer 190 billion USD.[72] In 2003, the EU agreed to extend the Common Agricultural Policy until 2013. Former UNDP Administrator Malloch Brown renewed calls for reform of the farm subsidies such as the CAP.[73]

Distorted global rice market

Japan is forced to import more than 767,000 tons of rice annually from the United States, Thailand, and other countries due to WTO rules,[74] although Japan produces over 100% of domestic rice consumption needs with 11 million tons produced in 2005 while 8.7 million tons were consumed in 2003–2004 period. Japan is not allowed to re-export this rice to other countries without approval. This rice is generally left to rot and then used for animal feed. Under pressure, the United States and Japan are poised to strike a deal to remove such restrictions. It is expected 1.5 million tons of high-grade American rice will enter the market soon.[75]

Crop shortfalls from natural disasters

Several distinct weather- and climate-related incidents have caused disruptions in crop production. Perhaps the most influential is the extended drought in Australia, in particular the fertile Murray-Darling Basin, which produces large amounts of wheat and rice. The drought has caused the annual rice harvest to fall by as much as 98% from pre-drought levels.[76]

Australia is historically the second-largest exporter of wheat after the United States, producing up to 25 million tons in a good year, the vast majority for export. However, the 2006 harvest was 9.8 million.[77] Other events that have negatively affected the price of food include the 2006 heat wave in California's San Joaquin Valley, which killed large numbers of farm animals, and unseasonable 2008 rains in Kerala, India, which destroyed swathes of grain. These incidents are consistent with the effects of climate change.[78][79]

The effects of Cyclone Nargis on Burma in May 2008 caused a spike in the price of rice. Burma has historically been a rice exporter, though yields have fallen as government price controls have reduced incentives for farmers. The storm surge inundated rice paddies up to 30 miles (48 km) inland in the Irrawaddy Delta, raising concern that the salt could make the fields infertile. The FAO had previously estimated that Burma would export up to 600,000 tons of rice in 2008, but concerns were raised in the cyclone's aftermath that Burma may be forced to import rice for the first time, putting further upward pressure on global rice prices.[13][80]

Stem rust reappeared in 1998[81] in Uganda (and possibly earlier in Kenya)[82] with the particularly virulent UG99 fungus. Unlike other rusts, which only partially affect crop yields, UG99 can bring 100% crop loss. Up to 80% yield losses were recently recorded in Kenya.[83]

As of 2005 stem rust was still believed to be "largely under control worldwide except in Eastern Africa".[82] But by January 2007 an even more virulent strain had gone across the Red Sea into Yemen. FAO first reported on 5 March 2008 that Ug99 had now spread to major wheat-growing areas in Iran.[84]

These countries in North Africa and Middle East consume over 150% of their own wheat production;[81] the failure of this staple crop thus adds a major burden on them. The disease is now expected to spread over China and the Far-East. The strong international collaboration network of research and development that spread disease-resistant strains some 40 years ago and started the Green Revolution, known as CGIAR, was since slowly starved of research funds because of its own success and is now too atrophied to swiftly react to the new threat.[81]

Soil and productivity losses

Sundquist[85] points out that large areas of croplands are lost year after year, due mainly to soil erosion, water depletion and urbanisation. According to him "60,000 km2/year of land becomes so severely degraded that it loses its productive capacity and becomes wasteland", and even more are affected to a lesser extent, adding to the crop supply problem.

Additionally, agricultural production is also lost due to water depletion. Northern China in particular has depleted much of its non-renewables aquifers, which now impacts negatively its crop production.[86]

Urbanisation is another, smaller, difficult to estimate cause of annual cropland reduction.[87]

Rising levels of ozone

One possible environmental factor in the food price crisis is rising background levels of ground-level tropospheric ozone in the atmosphere. Plants have been shown to have a high sensitivity to ozone levels, and lower yields of important food crops, such as wheat and soybeans, may have been a result of elevated ozone levels. Ozone levels in the Yangtze Delta were studied for their effect on oilseed rape, a member of the cabbage family that produces one-third of the vegetable oil used in China. Plants grown in chambers that controlled ozone levels exhibited a 10–20 percent reduction in size and weight (biomass) when exposed to elevated ozone levels. Production of seeds and oil was also reduced.[88] The Chinese authors of this study also reported that rice grown in chambers that controlled ozone levels exhibited a 14 to 20 percent reduction in biomass yield when exposed to ozone levels over 25 times higher than was normal for the region.[89]

Rising prices

From the beginning of 2007 to early 2008, the prices of some of the most basic international food commodities increased dramatically on international markets.[90] The international market price of wheat doubled from February 2007 to February 2008 hitting a record high of over US$10 a bushel.[91] Rice prices also reached ten-year highs. In some nations, milk and meat prices more than doubled, while soy (which hit a 34-year high price in December 2007[92]) and maize prices have increased dramatically.

Total food import bills rose by an estimated 25% for developing countries in 2007. Researchers from the Overseas Development Institute have suggested this problem will be worsened by a likely fall in food aid. As food aid is programmed by budget rather than volume, rising food prices mean that the World Food Programme (WFP) needs an extra $500 million just to sustain the current operations.[93]

To ensure that food remains available for their domestic populations and to combat dramatic price inflation, major rice exporters, such as China, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia and Egypt, imposed strict export bans on rice.[94] Conversely, several other nations, including Argentina, Ukraine, Russia, and Serbia either imposed high tariffs or blocked the export of wheat and other foodstuffs altogether, driving up prices still further for net food importing nations while trying to isolate their internal markets. North Korea suffered from the food crisis to such extent that a North Korean official was quoted in June '08 with saying "Life is more than difficult. It seems that everyone is going to die".[95] This nation however is solely relying on food assistance to cope with the crisis.[96]

In developed countries

United States

A May 2008 national survey found that food banks and pantries across the US were being forced to cut back on food distribution as 99 percent of respondents reported an increase in the number of people requesting services. Rising food and fuel prices, inadequate food stamp benefits, unemployment, underemployment, and rent or mortgage costs were factors reported as forcing an average of 15–20 percent more people.[97] Compounding this issue, USDA bonus foods have declined by $200 million and local food donations were down nationally about 9 percent over the same period. According to the California Association of Food Banks, which is an umbrella organization of nearly all food banks in the state, food banks are at the "beginning of a crisis."[98]

Effects on farmers

If global price movements are transmitted to local markets, farmers in the developing world could benefit from the rising price of food. According to researchers from the Overseas Development Institute, this may depend on farmers' capacity to respond to changing market conditions. Experience suggests that farmers lack the credit and inputs needed to respond in the short term. In the medium or long term, however, they could benefit, as seen in the Asian Green Revolution or in many African countries in the recent past.[93]

Relationship with 2008 Chinese milk scandal

As grain prices increased, China's numerous small-holding milk farmers, as well as producers of feed for cattle, were unable to exist economically. As a result, they turned to putting additives into the feed and milk, including melamine, to boost the measured level of protein. Hundreds of thousands of children became ill, China's milk exports virtually ended, executives and officials were arrested and some executed, and companies went bankrupt.[99]

Unrest and government actions in individual countries and regions

The price rises affected parts of Asia and Africa particularly severely with Burkina Faso,[100] Cameroon, Senegal, Mauritania, Côte d'Ivoire,[101] Egypt[102] and Morocco seeing protests and riots in late 2007 and early 2008 over the unavailability of basic food staples. Other countries that have seen food riots or are facing related unrest are: Mexico, Bolivia, Yemen, Uzbekistan, Bangladesh,[103] Pakistan,[104] Sri Lanka,[105] and South Africa.[106]

Bangladesh

10,000 workers rioted close to the Bangladeshi capital Dhaka, smashing cars and buses and vandalising factories in anger at high food prices and low wages. Dozens of people, including at least 20 police officials, were injured in the violence. Ironically, the country achieved food self-sufficiency in 2002, but food prices increased drastically due to the reliance of agriculture on oil and fossil fuels.[107]

Economists estimate 30 million of the country's 150 million people could go hungry.[108]

Brazil

In April 2008, the Brazilian government announced a temporary ban on the export of rice. The ban is intended to protect domestic consumers.[109][110]

Burkina Faso

One of the earlier food riots took place in Burkina Faso, on 22 February, when rioting broke out in the country's second and third largest cities over soaring food prices (up to a 65 percent increase), sparing the capital, Ouagadougou, where soldiers were mobilized throughout strategic points. The government promised to lower taxes on food and to release food stocks. Over 100 people were arrested in one of the towns.[111] Related policy actions of the Burkinabe government included:

- The removal of customs duty on rice, salt, dairy-based products and baby foods

- The removal of value added tax on durum wheat, baby foods, soap and edible oils

- Establishing negotiated prices with wholesalers for sugar, oil and rice

- Releasing food stocks

- Strengthening of community grain banks

- Food distribution in-kind

- Reduction of electricity cost, partial payment of utility bills for the poor

- Enacting special programs for schools and hospitals

- Fertilizer distribution and production support.

A ban was also imposed on exportation of cereals.[112]

Cameroon

Cameroon, the world's fourth largest cocoa producer, saw large scale rioting in late February 2008 in Douala, the country's commercial capital. Protesters were against inflating food and fuel prices, as well as the attempt by President Paul Biya to extend his 25-year rule. Protesters set up barricades, burned tires, and targeted businesses that they believed belonged to the Biya family, high members of the ruling party, the government, or France.[113] It became the first protest in the nation's history in which minute- by-minute events were covered by social media. By 27 February, a strike was taking place in thirty-one cities, including Yaoundé, Douala, Bamenda, Bafoussam, Buea, Limbe, Tiko, Muea, Mutengene, and Kumba.[113] At least seven people were killed in the worst unrest seen in the country in over fifteen years.[114] This figure was later increased to 24.[95] Youths were mobilized in ways that had not been seen since the days of the villes mortes.[113] Part of the government response to the protests was a reduction in import taxes on foods including rice, flour, and fish. The government reached an agreement with retailers by which prices would be lowered in exchange for the reduced import taxes. As of late April 2008, however, reports suggested that prices had not eased and in some cases had even increased.[115]

On 24 April 2008, the government of Cameroon announced a two-year emergency program designed to double Cameroon's food production and achieve food self-sufficiency.[116]

Côte d'Ivoire

On 31 March, Côte d'Ivoire's capital Abidjan saw police use tear gas and a dozen protesters injured following food riots that gripped the city. The riots followed dramatic hikes in the price of food and fuel, with the price of beef rising from US$1.68 to $2.16 per kilogram, and the price of gasoline rising from $1.44 to $2.04 per liter, in only three days.[117]

Egypt

In Egypt, a boy was killed from a gunshot to the head after Egyptian police intervened in violent demonstrations over rising food prices that gripped the industrial city of Mahalla on 8 April. Large swathes of the population have been hit as food prices, and particularly the price of bread, have doubled over the last several months as a result of producers exploiting a shortage that has existed since 2006[118] · .[119]

Ethiopia

Drought and the food price crisis threatened thousands in Ethiopia.[120]

Haiti

On 12 April 2008, the Haitian Senate voted to dismiss Prime Minister Jacques-Édouard Alexis after violent food riots hit the country.[121] The food riots caused the death of 5 people.[95] Prices for food items such as rice, beans, fruit and condensed milk have gone up 50 percent in Haiti since late 2007 while the price of fuel has tripled in only two months.[122] Riots broke out in April due to the high prices, and the government had been attempting to restore order by subsidizing a 15 percent reduction in the price of rice.[123] As of February 2010, post-earthquake Port-au-Prince is almost entirely reliant on foreign food aid, some of which ends up in the black markets.[124]

India

India has banned the export of rice except for Basmati which attracts a premium price.[125]

The ban has since been removed, and India now exports a variety of rice.

Indonesia

Street protests over the price of food took place in Indonesia[126] where food staples and gasoline have nearly doubled in price since January 2008.[127]

Latin America

In April 2008, the Latin American members of the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) met in Brasília to confront the issues of high food prices, scarcities and violence that affect the region.[128]

Mexico

The President of Mexico, Felipe Calderón, with industry representatives and members of the Confederation of Industrial Chambers (Concamin), agreed to freeze prices of more than 150 consumer staples, such as coffee, sardines, tuna, oil, soup or tea, among others, until the end of December 2008. The measure was carried out in an attempt to control inflation, which stood at an annual rate of 4.95%, the highest increase since December 2004.

Mexican baking company Grupo Bimbo's CEO, Daniel Servitje, announced in the 19th Plenary Meeting of the Mexico–China Business Committee that Bimbo agreed to freeze their product prices, despite a 20% rise in production costs.[129] Bimbo is one of the most important baking companies worldwide, having recently expanded to China. Bimbo has also acquired five bakeries in the United States and Canada.[130]

Mozambique

In mid February, rioting that started in the Mozambican rural town of Chokwe and then spread to the capital, Maputo, has resulted in at least four deaths. The riots were reported in the media to have been, at least in part, over food prices and were termed "food riots." A biofuel advocacy publication, however, claimed that these were, in fact, "fuel riots", limited to the rise in the cost of diesel, and argued that the "food riot" characterization worked to fan "anti-biofuels sentiment."[131]

Pakistan

The Pakistan Army has been deployed to avoid the seizure of food from fields and warehouses. This hasn't stopped the food prices from increasing. The new government has been blamed for not managing the countries food stockpiles properly.[132]

Myanmar

Once the world's top rice producer, has produced enough rice to feed itself until now. Rice exports dropped over four decades from nearly 4 million tons to only about 40,000 tons last year, mostly due to neglect by Myanmar's ruling generals of infrastructure, including irrigation and warehousing. On 3 May 2008 Cyclone Nargis stripped Myanmar's rice-growing districts, ruining large areas with salt water. U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that these areas produce 65 percent of Myanmar's rice. Worries of long-term food shortages and rationing are rife. The military regime says nothing about the rice crisis, but continues to export rice at the same rate. "...at least the next two harvests are going to be greatly affected and there'll be virtually no output from those areas during that time. So we're likely to see considerable food and rice shortages for the next couple of years. The damage to the economy is going to be profound." said economist and Myanmar expert Sean Turnell, of Australia's Macquarie University. (interviewed in "The Irriwaddy", Tuesday, 27 May 2008)

Panama

In Panama, in response to higher rice prices the government began buying rice at the high market price and selling rice to the public at a lower subsidized price at food kiosks.

Philippines

In the Philippines, the Arroyo government insisted on 13 April that there would be no food riots in the country and that there could be no comparison with Haiti's situation.[133] Chief Presidential Legal Counsel, Sergio Apostol stated that: "Haiti is not trying to solve the problem, while we are doing something to address the issue. We don't have a food shortage. So, no comparison..."[134] Comments by the Justice Secretary, Raul Gonzalez, the following day, that food riots are not far fetched, were quickly rebuked by the rest of the government.[135]

On 15 April, the Philippines, the world's largest rice importer, urged China, Japan, and other key Asian nations, to convene an emergency meeting, especially taking issue with those countries' rice export bans. "Free trade should be flowing", Philippine Agriculture Secretary Arthur Yap stated.[136] In late April 2008, the Philippines government requested that the World Bank exert pressure on rice exporting countries to end export restrictions.[137]

Russia

The Russian government pressured retailers to freeze food prices before key elections for fear of a public backlash against the rising cost of food in October 2007.[138] The freeze ended on 1 May 2008.[139]

Senegal

On 31 March 2008, Senegal had riots in response to the rise in the price of food and fuel. Twenty-four people were arrested and detained in a response that one local human rights group claimed included "torture" and other "unspeakable acts" on the part of the security forces.[140] Further protests took place in Dakar on 26 April 2008.[141]

Somalia

Riots in Somalia occurred on 5 May 2008 over the price of food, in which five protesters were killed. The protests occurred amid a serious humanitarian emergency due to the Ethiopian war in Somalia.

Tajikistan

The Christian Science Monitor, neweurasia, and other media observers are predicting that a nascent hunger crisis will erupt into a full famine as a consequence of the energy shortages.[142] UN experts announced on 10 October that almost one-third of Tajikistan's 6.7 million inhabitants may not have enough to eat for the winter of 2008–09.[143]

Yemen

Food riots in southern Yemen that began in late March and continued through early April, saw police stations torched, and roadblocks were set up by armed protesters. The army has deployed tanks and other military vehicles. Although the riots involved thousands of demonstrators over several days and over 100 arrests, officials claimed no fatalities; residents, however, claimed that at least one of the fourteen wounded people has died.[144]

Projections

The UN (FAO) released a study in December 2007 projecting a 49 percent increase in African cereal prices, and 53 percent in European prices, through July 2008.[145] In April 2008, the World Bank, in combination with the International Monetary Fund, announced a series of measures aimed at mitigating the crisis, including increased loans to African farmers and emergency monetary aid to badly affected areas such as Haiti.[146] According to FAO director Jacques Diouf, however, the World Food Programme needs an immediate cash injection of at least $1700 million,[11] far more than the tens of million-worth in measures already pledged. On 28 April 2008, the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon established a Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis under his chairmanship and composed of the heads of the United Nations specialized agencies, funds and programmes, Bretton Woods institutions and relevant parts of the UN Secretariat to co-ordinate efforts to alleviate the crisis.[147]

After the crisis

2013 research concluded that the spike was the result of an unusual combination of circumstances and prices in the future will be higher than before the spike, depending on oil prices, climate change, and future diets. The impacts of the spike on poor people were concentrated in low-income countries and may have been less severe than once thought, thanks to rising rural wages in some countries. The researchers called on developing countries to ensure good data on the key indicators of distress and to strengthen social protection, and on those involved in international development to continue increasing focus on reducing child malnutrition and stimulating agricultural development.[148]

Actions by governments

IFAD is making up to US$200 million available to support poor farmers boost food production in face of the global food crisis.[149]

On 2 May 2008, US President George W. Bush said he was asking Congress to approve an extra $770 million funding for international food aid.[150] On 16 October 2008, in a speech at a United Nations gathering on World Food Day, former US president Bill Clinton criticized the bipartisan coalition in Congress that blocked efforts to make some aid donations in cash rather than in food.[151] Referring in part to policies that had pressured African governments to reduce subsidies for fertilizer and other agricultural inputs, Clinton also said:

We need the World Bank, the IMF, all the big foundations, and all the governments to admit that, for 30 years, we all blew it, including me when I was President. We were wrong to believe that food was like some other product in international trade, and we all have to go back to a more responsible and sustainable form of agriculture.[152]

The release of Japan's rice reserves onto the market may bring the rice price down significantly. As of 16 May, anticipation of the move had already lowered prices by 14% in a single week.[153]

On 30 April 2008 Thailand announced the creation of the Organization of Rice Exporting Countries (OREC) with the potential to develop a price-fixing cartel for rice.[154][155] This is seen by some as an action to capitalise on the crisis.

In June 2008 the Food and Agriculture Organization hosted a High-Level Conference on World Food Security, in which $1.2 billion in food aid was committed for the 75 million people in 60 countries hardest hit by rising food prices.[156]

In June 2008, a sustained commitment from the G8 was called for by some humanitarian organizations.[157]

Food price decreases

In December 2008, the global economic slowdown, decreasing oil prices, and speculation of decreased demand for commodities worldwide brought about sharp decreases in the price of staple crops from their earlier highs. Corn prices on the Chicago Board of Trade dropped from US$7.99 per bushel in June to US$3.74 per bushel in mid-December; wheat and rice prices experienced similar decreases.[158] The UN's Food and Agriculture Organization, however, warned against "a false sense of security", noting that the credit crisis could cause farmers to reduce plantings.[159] FAO convened a World Summit on Food Security at its headquarters in Rome in November 2008, noting that food prices remained high in developing countries and that the global food security situation has worsened.

By early 2011 food prices had risen again to surpass the record highs of 2008. Some commentators saw this as the resumption of the price spike seen in 2007–08.[160] Prices had dropped after good weather helped increase grain yields while demand had dropped due to the recession.[161]

See also

References

- 1 2 "World Food Situation". FAO. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ↑ How do Food Prices Affect Producers and Consumers in Developing Countries?, ICTSD, Information Note Number 10, SEPTEMBER 2009

- ↑ UN Food and Agriculture Organization (2009). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2009. Rome.

- ↑ Rahman, M. Mizanur (11 August 2011). "Food price inflation: Global and national problem". The Daily Star.

- ↑ "Food Outlook" (PDF). FAO. November 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

Amid fears of a repeat of the price surge experienced in 2008, FAO expects supplies of major food crops in 2010/11 to be more adequate than two years ago, mainly because of much larger reserves.

- ↑ "The World Food Crisis". The New York Times. 10 April 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ↑ "Biofuels major cause of global food riots". Kazinform (Kazakhstan National Information Agency). 11 April 2008. Archived from the original on 26 January 2009.

- 1 2 "The cost of food: Facts and figures". BBC News. 16 October 2008.

- ↑ "Fear of rice riots as surge in demand hits nations across the Far East". Times Online. London.

- ↑ Katie Allen (18 July 2010). "Hedge funds accused of gambling with lives of the poorest as food prices soar". the Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Reguly, Eric (12 April 2008). "How the cupboard went bare". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008.

- ↑ Fischer, R. A.; Byerlee, Eric; Edmeades, E. O. "Can Technology Deliver on the Yield Challenge to 2050" (PDF). Expert Meeting on How to Feed the World. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: 12.

- 1 2 "Cyclone fuels rice price increase", BBC News, 7 May 2008

- ↑ World in grip of food crisis. IANS, Thaindian News. 7 April 2008.

- ↑ Burgonio, TJ (30 March 2008). "Runaway population growth factor in rice crisis—solon". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Manila. Archived from the original on 28 August 2015.

- ↑ World Population Information. United States Census Bureau. Data updated 27 March 2008.

- ↑ "World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision" (PDF). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. United Nations. 2013. p. 4.

- ↑ "World Grain Production and Consumption, 1960–2012". Earth Policy Institute.

The 2006 world grain harvest of 2,005 million tons, from the USDA Production, Supply, & Distribution database, was down 11 million tons from last year, or roughly 0.5%.

- ↑ U.S. non-food corn use (ethanol). http://www.earth-policy.org/datacenter/xls/indicator3_2006_4.xls

- ↑ "International Programs". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "World Population Clock: 7.3 Billion People (2015) – Worldometers". worldometers.info.

- ↑ von Braun, "High and Rising Food Prices", 2008, p 5, slide 14

- ↑ "World cereal supply could improve in 2008/09", FAO: Global cereal supply and demand brief, Crop Prospects and Food Situation, No. 2., April 2008. The report notes that: "[O]n a per capita basis, wheat and rice consumption levels decline marginally in the developing countries, mostly in favour of higher intakes of more value-added food, especially in China."

- ↑ Crop Prospects and Food Situation, No. 2, April 2008: Global cereal supply and demand brief, Growth in cereal utilization in 2007/08. Food and Agriculture Organization. United Nations. April 2008.

- ↑ Are We Approaching a Global Food Crisis? Between Soaring Food Prices and Food Aid Shortage Archived 22 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Katarina Wahlberg Global Policy Forum: World Economy & Development in Brief. 3 March 2008.

- ↑ Comment by Paul Collier on 2 May 2008 to the Financial Times The Economists' Forum blog post "Food crisis is a chance to reform global agriculture" by Martin Wolf, 30 April 2008

- ↑ "List of Foods By Environmental Impact and Energy Efficiency". True Cost – Analyzing our economy, government policy, and society through the lens of cost-benefit.

- ↑ ""High and Rising Food Prices: Why Are They Rising, Who Is Affected, How Are They Affected, and What Should Be Done?"" (PDF)., presentation by Joachim von Braun to the U.S. Agency for International Development conference Addressing the Challenges of a Changing World Food Situation: Preventing Crisis and Leveraging Opportunity, Washington, D.C., 11 April 2008, p. 3, slide 7

- ↑ http://research.cibcwm.com/economic_public/download/smay08.pdf (hamburgers replacing rice bowls)

- ↑ Bryan Lohmar, Fred Gale. "USDA ERS – Who Will China Feed?". USDA.

- ↑ "Fertilizer cost rising sharply: Result will be higher food prices". Sun Herald. Associated Press. 16 April 2008.

- ↑ Shortages Threaten Farmers' Key Tool: Fertilizer

- ↑ Reflections on the Global Food Crisis: How Did It Happen? How Has It Hurt? And How Can We Prevent the Next One?

- ↑ Barrows, Roth (1990). "Land Tenure and Investment in African Agriculture: Theory and Evidence". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 20 (2): 265–297. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00054458.

- ↑ "Productivity Growth in Indian Agriculture: The Role of Globalization and Economic Reform" (PDF). United Nations ESCAP. December 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Linking Globalization, Economic Growth and Poverty: Impacts of Agribusiness Strategies on Sub-Saharan Africa". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 83 (3): 722–729. August 2001. doi:10.1111/0002-9092.00197. JSTOR 1245106.

- ↑ The Food Bubble: How Wall Street Starved Millions and got away with it, by Frederick Kaufman, Harper's, 2010 July

- ↑ Democracy Now (radio show), Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzales, Interview with Frederick Kaufman, 2010 7 17

- ↑ TRNN – Jayati Ghosh (6 May 2010). "Global Food Bubble" (PDF). Pacific Free Press. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ Clearing the usual suspects, Buttonwood, The Economist, 2010 6 24

- ↑ "WDM food speculation campaign: Questions and answers" (PDF). World Development Movement. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2013.

- 1 2 Khor, Martin. The Impact of Trade Liberalisation on Agriculture in Developing Countries: The Experience of Ghana, Third World Network(2008) ISBN 978-983-2729-31-0

- ↑ Moseley, W.G., J. Carney and L. Becker. 2010. "Neoliberal Policy, Rural Livelihoods and Urban Food Security in West Africa: A Comparative Study of The Gambia, Côte d'Ivoire and Mali." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (13) 5774–5779.

- ↑ Paying the price for ignoring the real economy G. CHANDRASHEKHAR, The Hindu, 18 April 2008.

- ↑ "Planet Ark : Biofuels to Keep Global Grain Prices High – Toepfer". Planetark.com. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Grain Harvest Sets Record, But Supplies Still Tight | Worldwatch Institute". Worldwatch.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ Inslee, Jay; Bracken Hendricks (2007). "Apollo's Fire". Island Press, Washington, D.C.: 153–155, 160–161. ISBN 978-1-59726-175-3. . See Chapter 6. Homegrown Energy.

- ↑ Larry Rother (10 April 2006). "With Big Boost From Sugar Cane, Brazil Is Satisfying Its Fuel Needs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- 1 2 "Biofuels in Brazil: Lean, green and not mean". The Economist. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ↑ Julia Duailibi (27 April 2008). "Ele é o falso vilão". Veja Magazine (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- 1 2 3 Donald Mitchell (July 2008). "A note on Rising Food Crisis" (PDF). The World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.Policy Research Working Paper No. 4682. Disclaimer: This paper reflects the findings, interpretation, and conclusions of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank

- 1 2 "Etanol não influenciou nos preços dos alimentos". Veja Magazine (in Portuguese). Editora Abril. 28 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- 1 2 "Biofuels major driver of food price rise-World Bank". Reuters. 28 July 2008. Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- 1 2 Directorate for Trade and Agriculture, OECD (16 July 2008). "Economic Assessment of Biofuel Support Policies" (PDF). OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008. Disclaimer: This work was published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The views expressed and conclusions reached do not necessarily correspond to those of the governments of OECD member countries.

- 1 2 Directorate for Trade and Agriculture, OECD (16 July 2008). "Biofuel policies in OECD countries costly and ineffective, says report". OECD. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ↑ Oxfam (25 June 2008). "Another Inconvenient Truth: Biofuels are not the answer to climate or fuel crisis" (PDF). Oxfam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2008. Report available in pdf

- ↑ Oxfam (26 June 2008). "Another Inconvenient Truth: Biofuels are not the answer to climate or fuel crisis". Oxfam. Archived from the original on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ↑ "ONG diz que etanol brasileiro é melhor opção entre biocombustíveis" (in Portuguese). BBCBrasil. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ↑ Gernot Heller (17 April 2008). "Bad policy, not biofuel, drive food prices: Merkel". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ↑ "Press Conference by the President". The White House. 29 April 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ↑ Chakrabortty, Aditya (4 July 2008). "Secret report: biofuel caused food crisis". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ Sam Nelson (23 October 2008). "Ethanol no longer seen as big driver of food price". Reuters UK. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ↑ "The Effects of High Food Prices in Africa – Q&A", World Bank. Retrieved 6 May 2008

- ↑ Corcoran, Katherine (24 March 2008). "Food Prices Soaring Worldwide". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008.

- ↑ Regional Wheat Imports, Production, Consumption, and Stocks (Thousand Metric Tons), United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service 3 November 2008.

- ↑ Are We Approaching a Global Food Crisis? Between Soaring Food Prices and Food Aid Shortage Archived 22 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Katarina Wahlberg Global Policy Forum: World Economy & Development in Brief, 3 March 2008.

- ↑ Aditya Chakrabortty (4 July 2008). "Secret report: biofuel caused food crisis". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ↑ John M. Urbanchuk (11 July 2008). "Critique of World Bank Working Paper "A Note of Rising Food Prices"" (PDF). Renewable Fuel Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ↑ "As Prices Rise, Farmers Spurn Conservation Program" New York Times 9 April 2008. In England thousands of acres of land were "set-a-side" in hope to encourage wild birds and insects. This has had detrimental effects on the amount of food in England. Stockpiles of grain is virtually nil, which has made the price of bread excel over the past couple of months.

- ↑ Food crisis set to weigh on CAP Reform Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine., EurActiv, 20 May 2008

- ↑ Doha Development Round, Understanding the Issues Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. OECD, Doha Development Round

- ↑ Giving away the farm, the 2002 Farm Bill Food First, 8 July 2002

- ↑ Perfect Storm, The Rocketing Price of Food Guardian, 10 May 2008

- ↑ "Japan rice policy". United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Lewis, Leo (17 May 2008). "Japan's silos key to relieving rice shortage". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011.

- ↑ Drought in Australia reduces Australia’s rice crop by 98 percent. The New York Times, 17 April 2008.

- ↑ "Australia's food bowl lies empty", BBC News, 11 March 2008

- ↑ Food Prices Could Rise as Farmers in California's Prolific San Joaquin Valley Feel the Effects of Global Warming ABC News, 5 August 2006.

- ↑ Crops lost due to unseasonal rains in Kerala The Economic Times, 8 April 2008.

- ↑ "Scant Aid Reaching Burma's Delta" by Amy Kazmin and Colum Lynch, The Washington Post, 8 May 2008

- 1 2 3 "About this project". Durable Rust Resistance in Wheat. Cornell.

- 1 2 An assessment of race UG99 in Kenya and Ethiopia and the potential for impact in neighbouring regions and beyond. By expert panel on the stem-rust outbreak in Eastern Africa. 29 May 2005.

- ↑ Effect of a new race on wheat production/use of fungicides and its cost in large vs small scale farmers, situation of current cultivars. Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, 2005. Njoro. Cited in CIMMYT 2005 study.

- ↑ http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2008/1000805/index.html First report of wheat stem rust, strain Ug99, in Iran

- ↑ "Soils and Croplands Degradation". Home.alltel.net. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Managing China's Shrinking Groundwater Reserves". Skmconsulting.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Chapter 6 – Urbanization-caused topsoil loss". Home.alltel.net. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ Lower Crop Yields Due to Ozone a Factor in World Food Crisis Newswise. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ↑ Effects of elevated ozone on growth and yield of field-grown rice in Yangtze River Delta, China. Journal of Environmental Sciences, Volume 20, Issue 3, 2008.

- ↑ Timmer, Peter C. (2010). "Reflections on food crises past". Food Policy. 35 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.09.002.

- ↑ Wheat breaks through $10 a bushel, BBC, 17 December 2007.

- ↑ Corn's key role as food and fuel, Adam Brookes BBC News, 17 December 2007.

- 1 2 Rising Food Prices: A Global Crisis, Overseas Development Institute, 22 April 2008.

- ↑ "The global food crisis and the Indian situation". Navhind Times. 14 April 2008. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 Time; Food Prices:What went wrong (16 June 2008)

- ↑ "North Korea faces 'looming' food crisis". BBC News. 10 April 2002.

- ↑ “New Survey Underscores Urgent Need For Farm Bill As Demands Are Up, Food Down”, "America's Second Harvest", 12 May 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ↑ “International Food Crisis: Food Bank Clients in Peril”, California Association of Food Banks, 2008-6. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ↑ China milk scandal: Families of sick children fight to find out true scale of the problem – Telegraph Malcolm Moore, photos Daniel Traub, 2008 03 12, via www.telegraph.co.uk on 2010 11 10

- ↑ Burkina general strike starts over cost of living Mathieu Bonkoungou: Reuters, 8 April 2008

- ↑ Riots prompt Ivory Coast tax cuts, BBC, 2 April 2008. COTE D'IVOIRE: Food price hikes spark riots, 31 March 2008 (IRIN)

- ↑ Egyptians hit by rising food prices, BBC, 11 March 2008.

Two die after clashes in Egypt industrial town Gamal: Reuters, 8 April 2008. - ↑ "Soaring Food Prices Spark Unrest", The Philadelphia Trumpet, 11 April 2008

- ↑ "Pakistan heading for yet another wheat crisis", The Independent, 1 April 2008

- ↑ "Anger grows over rising prices in Sri Lanka", World Socialist Web Site, 11 April 2008

- ↑ Boyle, Brendan (13 April 2008). "SA must grow food on all arable land, says Manuel". The Times. Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009.

- ↑ "Bangladesh workers riot over soaring food prices". Yahoo News. Agence France-Presse. 12 April 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008.]

- ↑ Julhas Alam The Associated Press. "Bangladesh in critical shape as people desperate for food". Arizona Daily Star.

- ↑ Olle, N. 2008, 'Brazil halts rice exports as world food prices climb', ABC News (Aust.), 25 April. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ↑ The Real News 2008, 'Brazil bans rice exports, protests in Peru', The Real News, 26 April. Retrieved 28 April 2008. (Video.)

- ↑ "Burkina Faso: Food riots shut down main towns", IRIN, 22 February 2008

- ↑ "Polovinkin, Sergey. Food Crisis and Food Security Policies in West Africa: An Inventory of West African Countries' Policy Responses During the 2008 Food Crisis. Version 9. Knol. 2010 Apr 11.". Google. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 Amin, J. (2012). "Understanding the Protest of February 2008 in Cameroon". Africa Today. 58 (4): 20–43. doi:10.1353/at.2012.0027.

- ↑ "Anti-government rioting spreads in Cameroon". International Herald Tribune. Reuters. 27 February 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009.

- ↑ IRIN 2008, 'CAMEROON: Lifting of import taxes fails to reduce food prices', 29 April. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ↑ IRIN 2008, 'Cameroon: Food self-sufficient in two years?', IRIN, 25 April. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ "Côte d'Ivoire: Food Price Hikes Spark Riots", AllAfrica.com, 31 March 2008.

- ↑ "Egyptian boy dies from wounds sustained in Mahalla food riots". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 8 April 2008. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008.

- ↑ Steavenson, Wendell (9 January 2009). "It's the baladi, stupid". The Australian Financial Review. p. Perspectives Review supplement (pp. 3–5).

The difference between the subsidised and market price of bread [in Egypt] is exploited at every stage of production and sale, by importers, millers, warehousers, traders, bakers and consumers alike.

- ↑ A malnourished Ethiopian infant is comforted by her mother at a relief camp in 2005. Addis Ababa says the number of Ethiopians in need of emergency food aid in drought-affected regions has risen to 4.5 million. 2007 AFP Boris Heger (3 June 2008). "France 24 | 4.5 million drought-stricken Ethiopians need food aid: govt | France 24". France24.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Haiti PM ousted over soaring food prices". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 13 April 2008. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "The world food crisis", Jamaica Gleaner, 13 April 2008

- ↑ "Price of rice prompts renewed anger in Haiti", Reuters, April l5, 2008

- ↑ "Foreign Food Aid Trickles Into Haiti's Black Market", New York Times, 4 February 2010

- ↑ Julian Borger. "Feed the world? We are fighting a losing battle, UN admits". the Guardian.

- ↑ "Indonesia takes action over soyabeans", Iran Daily, 16 January 2008

- ↑ Coren, Michael (12 April 2008). "Food beyond the reach of the poor". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Latin America: Food or Fuel – That Is the Burning Question Upside Down World, 15 April 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2009. Archived 21 May 2009.

- ↑ "Bimbo busca mantener sus precios durante 2009". El Universal. 28 August 2015.

- ↑ "Company News; Grupo Bimbo of Mexico Buys 5 Bakeries in United States". The New York Times. 23 January 2002. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ "Mozambique diesel riots reported in Western media as “food riots”, fanning anti-biofuels sentiment", Biofuel Digest, 19 February 2008

- ↑ zawya.com (need to be login first)

- ↑ "Palace assures no food riots in RP", Sun Star Network Exchange (Sunnex), 13 April 2008

- ↑ "Official: Philippines not comparable with Haiti in food crisis", Xinhua, 13 April 2008

- ↑ "Food riots to hit Manila soon?", United Press International, 14 April 2008

- ↑ "Manila calls for Asian summit over food crisis", The Standard, 15 April 2008

- ↑ "Manila urges end to rice export ban". Al Jazeera English. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ↑ "Kremlin orders a freeze on food prices as country gets set for polls". Times Online. London. 26 October 2007. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011.

- ↑ Titova, Irina (12 May 2008). "Food Prices Forecast to Keep Rising". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ↑ "Senegal: Heavy handed response to food protesters", IRIN, 31 March 2008

- ↑ "Food costs spark protests in Senegal". Al Jazeera English. 27 April 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ Vadim (4 March 2008). "Hunger to replace energy crisis". neweurasia. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ↑ Tajikistan: Almost One-Third of the Population Is in Danger of Going Hungry This Winter, EurasiaNet

- ↑ "Food riots rock Yemen", The Intelligence Daily, 4 April 2008.

- ↑ Cereal prices hit poor countries, BBC, 14 February 2008.

UN warns on soaring food prices, 17 December 2007. - ↑ World Bank tackles food emergency, BBC, 14 April 2008.

- ↑ UN Sets up food crisis task force, BBC, 29 April 2008.

- ↑ Steve Wiggins and Sharada Keats, July 2013, Looking back, peering forward: what has been learned from the food-price spike of 2007–2008? http://www.odi.org.uk/publications/7384-look-back-peering-forward-food-price-spike

- ↑ "US$200 million from IFAD to help poor farmers boost food production in face of food crisis". ifad.org.

- ↑ "Bush offers $770m for food crisis". BBC News. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ Hanley, Charles J. (23 October 2008). "'We blew it' on global food, says Bill Clinton". The San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ↑ Bill Clinton, "Speech: United Nations World Food Day", October 13, 2008

- ↑ Leo Lewis, Asia Business Correspondent (16 May 2008). "Rice price dives as US and Japan set to unlock grain pact – Times Online". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Mekong nations to form rice price-fixing cartel". radioaustralia.net.au.

- ↑ Post|1 May 2008|PM floats idea of five-nation rice cartel

- ↑ "UN increases food aid by $1.2bn", BBC News, 4 June 2008

- ↑ "Center for Global Development : Food Crisis Requires Sustained Commitment from the G8". Cgdev.org. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Corn Caps Record Week, Soybeans Drop on Shifts in U.S. Planting". Bloomberg. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ↑ "Another food crisis year looms, says FAO". Financial Times. 6 November 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ↑ "Medium- to Long-Run Implications of High Food Prices for Global Nutrition". Journal of Nutrition. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ Brown, Lester (May–June 2011). "The New Geopolitics of Food". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

External links

- Food and Agriculture Organization FAO World Food Situation Portal Food and Agriculture Organization

- World Summit on Food Security 2009

- Reuters – Special Coverage: Agflation

- International Food Policy Research Institute – Research Area: Food Prices

- Research Brief: State of Food Insecurity & Opportunities in Muslim Countries – DinarStandard Research Brief

- Anti-Hunger Protests Rock Haiti. 2008. North American Congress on Latin America, by Jeb Sprague

- Crisis briefing on food and hunger from Reuters AlertNet

- The Food Bubble: How Wall Street Starved Millions and Got Away With It – video report with Frederick Kaufman by Democracy Now!

- Feeding Nine Billion