1962 Rajshahi massacres

| Part of a series on |

| Persecution of Bengali Hindus |

|---|

Part of Bengali Hindu history |

| Discrimination |

| Persecution |

| Opposition |

|

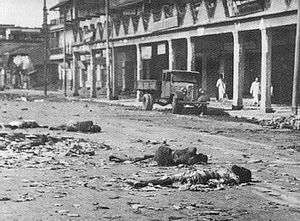

The Rajshahi massacres took place in April 1962, marked by widespread ethnic violence and killings of minorities in Rajshahi and Pabna districts of East Pakistan (present Bangladesh). [1][2] Their properties and womenfolk were attacked.[3] More than three thousand non-Muslims died in the massacre. [4]

Background

In 1958, Ayub Khan led military junta came to power in Pakistan. From the very beginning, the policy of the Ayub regime was to cleanse East Pakistan of the Bengali Hindu and other minorities.

Killings

On 22 March 1962, an ethnic riot broke out between the Santhals and the Muslims in the Malda district of West Bengal.[5] The Santhals, armed with bows and arrows, shot dead three Muslims while six were burnt to death. On 20 April, the ethnic tension between the two groups led to another ethnic riot. In five days of violence, five Muslims were killed and 64 people were injured.

The Pakistani press not only published exaggerated figures of Muslim casualties in Maldah district, but also stated that 1,000 Muslims were killed in Murshidabad district, even though there was no incident of ethnic violence in the district. Pakistan Radio too broadcast false stories of atrocities on minorities in India.[4] On 22 April, Lieutenant General Muhammad Azam Khan, the Governor of East Pakistan, delivered an inflammatory speech with imaginary stories of torture on minorities in India. On 23 April, the Bengali Hindus and other ethnic minorities were attacked in the Rajshahi Division. The District Magistrate of Rajshahi did not take any steps to stop the attacks. Killings, rape, loot and arson continued for days. They were attacked in the passenger trains at the Rajshahi railway station and in the market adjacent to the Natore railway station.[6] In Sarusa village of Hujuri Para Union under Paba police station, the Hindus were attacked and many were seriously afflicted.[7] In Darsa village under Paba police station 1,200 people were killed.[6] An estimated 3,000-5,000 non-Muslims were killed in Rajshahi district alone.[6]

The Assistant High Commissioner in Rajshahi came to the rescue of the minorities. The intervention of the Indian Assistant High Commission at resulted in the troops being called and the massacre was stopped.[4] The Pakistan government whipped up a war hysteria and the Indian Deputy High Commission at Dhaka was placed under military guard.[8] It was impossible for the Indian Deputy High Commission to collect information on the attacks on the minorities. Rajeshwar Dayal, the Indian High Commissioner to Pakistan who had come to Dhaka too, was not allowed to visit the districts of Rajshahi and Pabna.[8]

Exodus

Around 11,000 Santhals and Rajbanshis migrated to India.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Dey, Ishita (June 2009). "On the Margins of Citizenship: Principles of Care and Rights of the Residents of the Ranaghat Women's Home, Nadia District" (PDF). Refugee Watch. Kolkata: Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (33): 4. ISSN 2347-405X. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ↑ Sen, Uditi (2011). "Spinster, Prostitute or Pioneer? Images of Refugee Women in Post-Partition Calcutta" (PDF). EUI Working Papers. Florence: European University Institute. 34. ISSN 1830-7728. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay, Kali Prasad (2007). Partition, Bengal and After: The Great Tragedy of India. New Delhi: Reference Press. p. 45. ISBN 81-8405-034-8.

- 1 2 3 Ray, Jayanta Kumar (September 1968). Democracy and Nationalism on Trial (First ed.). Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study. p. 216.

- ↑ "Keesing's Contemporary Archives" (PDF). Keesing's Contemporary Archives. Stanford University. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Lahiry, Pravash Chandra (1964). India Partitioned And Minorities In Pakistan. Writer's Forum. pp. 54–55. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ↑ "Paba Upazila". Hello Bangladesh. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- 1 2 Ray, Jayanta Kumar (September 1968). Democracy and Nationalism on Trial (First ed.). Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study. p. 239.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the Ministry of External Affairs for 1962-63". Ministry of External Affairs, India. p. 20. Retrieved 23 August 2014.