Berlin Crisis of 1961

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Berlin |

| Margraviate of Brandenburg (1157–1806) |

| Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918) |

| German Empire (1871–1918) |

| Weimar Republic (1919–33) |

| Nazi Germany (1933–45) |

| West Germany and East Germany (1945–90) |

|

| Federal Republic of Germany (1990–present) |

| See also |

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 (4 June – 9 November 1961) was the last major politico-military European incident of the Cold War about the occupational status of the German capital city, Berlin, and of post–World War II Germany. The USSR provoked the Berlin Crisis with an ultimatum demanding the withdrawal of Western armed forces from West Berlin—culminating in the city's de facto partition with the East German erection of the Berlin Wall.

The 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union—the last to be attended by the Communist Party of China—was held in Moscow during the crisis.

Background

Emigration through Berlin "loophole"

After the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe at the end of World War II, some of those living in the newly acquired areas of the Eastern Bloc aspired to independence and wanted the Soviets to leave.[1] Between 1945 and 1950, over 15 million people emigrated from Soviet-occupied Eastern European countries to the West.[2] Taking advantage of this route, the number of Eastern Europeans applying for political asylum in West Germany was 197,000 in 1950, 165,000 in 1951, 182,000 in 1952 and 331,000 in 1953.[3]

By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to controlling national movement, restricting emigration, was emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc, including East Germany.[4] Up until 1953, the lines between East Germany and the western occupied zones could be easily crossed in most places.[5] Consequently, the Inner German border between the two German states was closed, and a barbed-wire fence erected. In 1955, the Soviets passed a law transferring control over civilian access in Berlin to East Germany, which officially abdicated them for direct responsibility of matters therein, while passing control to a government not recognized in the US-allied West.[6] When large numbers of East Germans then defected under the guise of "visits", the new East German state essentially eliminated all travel between the west and east in 1956.[5]

With the closing of the Inner German border officially in 1952,[7] the border in Berlin remained considerably more accessible than the rest of the border because it was administered by all four occupying powers.[5] Accordingly, Berlin became the main route by which East Germans left for the West.[8] The Berlin sector border was essentially a "loophole" through which Eastern Bloc citizens could still escape.[7] The 4.5[9] million East Germans that had left by 1961 totaled approximately 20% of the entire East German population.[10] The loss was disproportionately heavy among professionals—engineers, technicians, physicians, teachers, lawyers and skilled workers.[10] The brain drain of professionals had become so damaging to the political credibility and economic viability of East Germany that closing this loophole and securing the Soviet-imposed East-West-Berlin frontier was imperative.[11]

Berlin ultimatum

In November 1958, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev issued the Western powers an ultimatum to withdraw from Berlin within six months and make it a free, demilitarised city. Khrushchev declared that, at the end of that period, the Soviet Union would turn over control of all lines of communication with West Berlin to East Germany, meaning the western powers would have access to West Berlin only when East Germany permitted it. In response, the United States, United Kingdom, and France clearly expressed their strong determination to remain in, and maintain their legal right of free access to, West Berlin.[12]

The Soviet Union withdrew its deadline in May 1959, and the foreign ministers of the four countries spent three months meeting. They did not come to any major agreements, but this process led to negotiations and to Khrushchev's September 1959 visit to the US, at the end of which he and US President Dwight Eisenhower jointly asserted that general disarmament was of utmost importance and that such issues as that of Berlin "should be settled, not by the application of force, but by peaceful means through negotiations."[12]

Eisenhower and Khrushchev had a few days together at the US presidential retreat Camp David, where they talked frankly with each other. "There was nothing more inadvisable in this situation," said Eisenhower, "than to talk about ultimatums, since both sides knew very well what would happen if an ultimatum were to be implemented." Khrushchev responded that he did not understand how a peace treaty could be regarded by the American people as a "threat to peace". Eisenhower admitted that the situation in Berlin was "abnormal" and that "human affairs got very badly tangled at times."

Khrushchev came away with the impression that a deal was possible over Berlin, and they agreed to continue the dialogue at a summit in Paris in May 1960. However, the Paris Summit that was to resolve the Berlin question was cancelled in the fallout from Gary Powers's failed U-2 spy flight on 1 May 1960.

Escalation and crisis

Meeting with US President John F. Kennedy in the Vienna summit on 4 June 1961, Premier Khrushchev again raised tensions by reissuing his threat to sign a separate peace treaty with East Germany and thus end the existing four-power agreements guaranteeing American, British, and French rights to access West Berlin.[12] However, this time he did so by issuing an ultimatum, with a deadline of 31 December 1961. The three powers responded that any unilateral treaty could not affect their responsibilities and rights in West Berlin.[12]

In the growing confrontation over the status of Berlin, Kennedy undercut his own bargaining position during his Vienna summit negotiations with Khrushchev in June 1961. Kennedy essentially conveyed US acquiescence to the permanent division of Berlin. This made his later, more assertive public statements less credible to the Soviets.[13]

As the confrontation over Berlin escalated, Kennedy, in a speech delivered on nationwide television the night of 25 July, reiterated that the United States was not looking for a fight and that he recognised the "Soviet Union's historical concerns about their security in central and eastern Europe." He said he was willing to renew talks, but he also announced that he would ask Congress for an additional $3.25 billion for military spending, mostly on conventional weapons. He wanted six new divisions for the Army and two for the Marines, and he announced plans to triple the draft and to call up the reserves. Kennedy proclaimed: "We seek peace, but we shall not surrender."

The same day, Kennedy requested an increase in the Army's strength from 875,000 to approximately 1 million troops, an increase of 29,000 and 63,000 troops in the active duty Navy and Air Force, respectively, and the authority to bring some reserve units into active duty. He also ordered that draft calls be doubled, and asked for additional funds to identify and mark space in existing structures that could be used for fall-out shelters, to stock these shelters with essentials for survival, and to improve air-raid warning and fallout detection systems.[12]

Vacationing in the Black Sea resort of Sochi, Khrushchev was reported to be angered by Kennedy's speech. John Jay McCloy, Kennedy's disarmament adviser, who happened to be in the Soviet Union, was invited to join Khrushchev. It is reported that Khrushchev explained to McCloy that Kennedy's military build-up threatened war.

The Berlin Wall

In early 1961, the East German government sought a way to stop its population leaving to the West. Walter Ulbricht, First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and Staatsrat chairman and thus East Germany's chief decision-maker, convinced the Soviet Union that force was necessary to stop this movement, although Berlin's four-power status required the allowance of free travel between zones and forbade the presence of German troops in Berlin.[12]

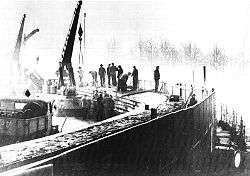

The East German government began stockpiling building materials for the erection of the Berlin Wall; this activity was widely known, but only a small circle of Soviet and East German planners believed that East Germany were aware of the purpose.[12] This material included enough barbed wire to enclose the 96-mile circumference of West Berlin. The regime managed to avoid suspicion by spreading out the purchases of barbed wire among several East German companies, which in turn spread their orders out among a range of firms in West Germany and the United Kingdom.[14]

On 15 June 1961, two months before the construction of the Berlin Wall started, Walter Ulbricht stated in an international press conference: "Niemand hat die Absicht, eine Mauer zu errichten!" ("No one has the intention to erect a wall"). It was the first time the term Mauer (wall) had been used in this context.

On 4–7 August 1961, the foreign ministers of the US, UK, France and West Germany secretly met in Paris to discuss how to respond to the Soviet actions in West Berlin. They expressed a lack of willingness to engage in warfare. Within weeks, the KGB provided Khrushchev with descriptions of the Paris talks. These showed that US Secretary of State Dean Rusk, unlike the West Germans, supported talks with the Soviet Union, though the KGB and the GRU warned that the US were being pressured by other members of the alliance to consider economic sanctions against East Germany and other socialist countries and to move faster on plans for conventional and nuclear armament of their allies in Western Europe, such as the West German Bundeswehr.[15]

The West had advance intelligence about the construction of the Wall. On 6 August, a HUMINT source, a functionary in the SED, provided the 513th Military Intelligence Group (Berlin) with the correct date of the start of construction. At weekly meeting of the Berlin Watch Committee on 9 August 1961, the Chief of the US Military Liaison Mission to the Commander Group of Soviet Forces Germany predicted the construction of a wall. An intercept of SED communications on the same day informed the West that there were plans to begin blocking all foot traffic between East and West Berlin. The interagency intelligence Watch Committee assessment said that this intercept "might be the first step in a plan to close the border", which turned out to be correct.

On Saturday 12 August 1961, the leaders of East Germany attended a garden party at a government guesthouse in Döllnsee, in a wooded area to the north of East Berlin, and Walter Ulbricht signed the order to close the border and erect a Wall.

At midnight, the army, police, and units of the East German army began to close the border and by morning on Sunday 13 August 1961 the border to West Berlin had been shut. East German troops and workers had begun to tear up streets running alongside the barrier to make them impassable to most vehicles, and to install barbed wire entanglements and fences along the 156 km (97 mi) around the three western sectors and the 43 km (27 mi) which actually divided West and East Berlin. Approximately 32,000 combat and engineer troops were employed for the building of the Wall, after which the Border Police became responsible for manning and improving it. To discourage Western interference and perhaps control potential riots, the Soviet Army was present.[12]

On 30 August 1961, in response to moves by the Soviet Union to cut off access to Berlin, President Kennedy ordered 148,000 Guardsmen and Reservists to active duty. In October and November, more Air National Guard units were mobilised, and 216 aircraft from the tactical fighter units flew to Europe in operation "Stair Step", the largest jet deployment in the history of the Air Guard. Most of the mobilised Air Guardsmen remained in the US, while some others had been trained for delivery of tactical nuclear weapons and had to be retrained in Europe for conventional operations. The Air National Guard's ageing F-84s and F-86s required spare parts that the United States Air Forces in Europe lacked.[12]

Richard Bach wrote his book Stranger to the Ground centred around his experience as an Air National Guard pilot on this deployment.

Stand-off between US and Soviet tanks

The four powers governing Berlin (Soviet Union, United States, United Kingdom, and France) had agreed at the 1945 Potsdam Conference that Allied personnel could move freely in any sector of Berlin. But on 22 October 1961, just two months after the construction of the Wall, the US Chief of Mission in West Berlin, E. Allan Lightner, was stopped in his car (which had occupation forces license plates) while crossing at Checkpoint Charlie to go to a theatre in East Berlin. The former Army General Lucius D. Clay, US President John F. Kennedy's Special Advisor in West Berlin, decided to demonstrate American resolve.

Clay sent an American diplomat, Albert Hemsing, to probe the border. While probing in a vehicle clearly identified as belonging to a member of the US Mission in Berlin, Hemsing was stopped by East German police asking to see his passport. Once his identity became clear, US Military Police were rushed in. The Military Police escorted the diplomatic car as it drove into East Berlin and the shocked GDR police got out of the way. The car continued and the soldiers returned to West Berlin. A British diplomat — British cars were not immediately recognisable as belonging to the staff in Berlin — was stopped the next day and showed his identity card identifying him as a member of the British Military Government in Berlin, infuriating Clay.

US Commandant General Watson was outraged by the East Berlin police's attempt to control the passage of American military forces. He communicated to the Department of State on 25 October 1961 that Soviet Commandant Colonel Solovyev and his men were not doing their part to avoid disturbing actions during a time of peace negotiations, and demanded that the Soviet authorities take immediate steps to remedy the situation. Solovyev replied by describing American attempts to send armed soldiers across the checkpoint and keeping American tanks at sector boundary as an "open provocation" and a direct violation of GDR regulations. He insisted that properly identified American military could cross the sector border without impediments, and were only stopped when their nationality was not immediately clear to guards. Solovyev contended that requesting identifying paperwork from those crossing the border was not unreasonable control; Watson disagreed. In regards to the American military presence on the border, Solovyev warned:

I am authorized to state that it is necessary to avoid actions of this kind. Such actions can provoke corresponding actions from our side. We have tanks too. We hate the idea of carrying out such actions, and are sure that you will re-examine your course.[16]

Perhaps this contributed to Hemsing's decision to make the attempt again: on 27 October 1961, Mr. Hemsing again approached the zonal boundary in a diplomatic vehicle. But Clay did not know how the Soviets would respond, so just in case, he had sent tanks with an infantry battalion to the nearby Tempelhof airfield. To everyone's relief the same routine was played out as before. The US Military Police and Jeeps went back to West Berlin, and the tanks waiting behind also went home.

|

| |

|

|

Immediately afterwards, 33 Soviet tanks drove to the Brandenburg Gate. Curiously, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev claimed in his memoirs that as he understood it, the American tanks had seen the Soviet tanks coming and retreated. Col. Jim Atwood, then Commander of the US Military Mission in West Berlin, disagreed in later statements. As one of the first to spot the tanks when they arrived, Lieutenant Vern Pike was ordered to verify whether they were indeed Soviet tanks. He and tank driver Sam McCart drove over to East Berlin, where Pike took advantage of a temporary absence of any soldiers near the tanks to climb into one of them. He came out with definitive evidence that the tanks were Soviet, including a Red Army newspaper.[17]

Ten of these tanks continued to Friedrichstraße, and stopped just 50 to 100 metres from the checkpoint on the Soviet side of the sector boundary. The US tanks turned back towards the checkpoint, stopping an equal distance from it on the American side of the boundary. From 27 October 1961 at 17:00 until 28 October 1961 at about 11:00, the respective troops faced each other. As per standing orders, both groups of tanks were loaded with live munitions. The alert levels of the US Garrison in West Berlin, then NATO, and finally the US Strategic Air Command (SAC) were raised. Both groups of tanks had orders to fire if fired upon.

It was at this point that US Secretary of State Dean Rusk conveyed to General Lucius Clay, the US commanding officer in Berlin, that "We had long since decided that Berlin is not a vital interest which would warrant determined recourse to force to protect and sustain." Clay was convinced that having US tanks use bulldozer mounts to knock down parts of the Wall would have ended the Crisis to the greater advantage of the US and its allies without eliciting a Soviet military response. His views, and corresponding evidence that the Soviets may have backed down following this action, support a more critical assessment of Kennedy's decisions during the crisis and his willingness to accept the Wall as the best solution.[18]

With KGB spy Georgi Bolshakov serving as the primary channel of communication, Khrushchev and Kennedy agreed to reduce tensions by withdrawing the tanks.[19] The Soviet checkpoint had direct communications to General Anatoly Gribkov at the Soviet Army High Command, who in turn was on the phone to Khrushchev. The US checkpoint contained a Military Police officer on the telephone to the HQ of the US Military Mission in Berlin, which in turn was in communication with the White House. Kennedy offered to go easy over Berlin in the future in return for the Soviets removing their tanks first. The Soviets agreed. Kennedy stated concerning the Wall: "It's not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war."[20]

A Soviet tank moved about 5 metres backwards first; then an American tank followed suit. One by one the tanks withdrew. But General Bruce C. Clarke, then the Commander-in-Chief (CINC) of US Army Europe (USAREUR), was said to have been concerned about Clay's conduct and Clay returned to the United States in May 1962. Gen. Clarke's assessment may have been incomplete, however: Clay's firmness had a great effect on the German population, led by West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt and West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

Notes

- ↑ Thackeray 2004, p. 188

- ↑ Böcker 1998, p. 207

- ↑ Loescher 2001, p. 60

- ↑ Dowty 1989, p. 114

- 1 2 3 Dowty 1989, p. 121

- ↑ Harrison 2003, p. 98

- 1 2 Harrison 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Paul Maddrell, Spying on Science: Western Intelligence in Divided Germany 1945–1961, p. 56. Oxford University Press, 2006

- ↑ https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1N7aUJ0z1gBpSAWDbLHwEbNqDp7sGodbXVvIRKNhQcD4/edit#slide=id.ga01456a75_1_0

- 1 2 Dowty 1989, p. 122

- ↑ Pearson 1998, p. 75

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Berlin Crisis". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ Kempe, Frederick (2011). Berlin 1961. Penguin Group (USA). p. 247. ISBN 0-399-15729-8.

- ↑ Kempe, Frederick (2011). Berlin 1961. Penguin Group (USA). p. 324. ISBN 0-399-15729-8.

- ↑ Zubok, Vladislav M. (1994). "Spy vs. Spy: The KGB vs. the CIA".

- ↑ Department of State|Office of the Historian|Foreign Relations of The United States|Berlin Crisis|1961–1962|Document 192

- ↑ Kempe, Frederick (2011). Berlin 1961. Penguin Group (USA). pp. 470–471. ISBN 0-399-15729-8.

- ↑ Kempe, Frederick (May 2011). Berlin 1961. Penguin Group (USA). pp. 474–476. ISBN 0-399-15729-8.

- ↑ Kempe, Frederick (2011). Berlin 1961. Penguin Group (USA). pp. 478–479. ISBN 0-399-15729-8.

- ↑ Gaddis, John Lewis, The Cold War: A New History (2005), p. 115.

References

- British Garrison Berlin 1945 -1994, "No where to go", W. Durie ISBN 978-3-86408-068-5

- Böcker, Anita (1998), Regulation of Migration: International Experiences, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 90-5589-095-2

- Dowty, Alan (1989), Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-04498-4

- Pearson, Raymond (1998), The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire, Macmillan, ISBN 0-312-17407-1

- Thackeray, Frank W. (2004), Events that changed Germany, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32814-5

- The Wall, 1958–1963

- Forty Years Crisis

- First strike options and the Berlin Crisis

- The 1961 Berlin Crisis and Soviet Preparations for War in Europe

- Khrushchev’s Secret Speech on the Berlin Crisis, August 1961

- Khrushchev and the Berlin Crisis (1958–1962)

- Conference: "From Vienna to Checkpoint Charlie: The Berlin Crisis of 1961"

- The short film Big Picture: Operation Readiness is available for free download at the Internet Archive