1947 Fort Lauderdale hurricane

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Damage in Delray Beach, Florida | |

| Formed | September 4, 1947 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 20, 1947 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 938 mbar (hPa); 27.7 inHg |

| Fatalities | 51 direct[1] |

| Damage | $110 million (1947 USD) |

| Areas affected | The Bahamas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi |

| Part of the 1947 Atlantic hurricane season | |

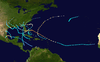

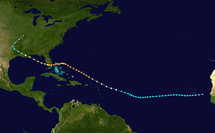

The 1947 Fort Lauderdale hurricane was an intense tropical cyclone that affected the Bahamas, southernmost Florida, and the Gulf Coast of the United States in September 1947. The fourth Atlantic tropical cyclone of the year, it formed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean on September 4, becoming a hurricane, the third of the 1947 Atlantic hurricane season, less than a day later. After moving south by west for the next four days, it turned to the northwest and rapidly attained strength beginning on September 9. It reached a peak intensity of 145 mph (233 km/h) on September 15 while approaching the Bahamas. In spite of contemporaneous forecasts that predicted a strike farther north, the storm then turned to the west and poised to strike South Florida, crossing first the northern Bahamas at peak intensity. In the Bahamas, the storm produced a large storm surge and heavy damage, but with no reported fatalities.

A day later, the storm struck South Florida as a Category 4 hurricane, its eye becoming the first and only of a major hurricane to strike Fort Lauderdale. In Florida, advance warnings and stringent building codes were credited with minimizing structural damage and reducing loss of life to 17 people, but nevertheless widespread flooding and coastal damage resulted from heavy rainfall and high tides. Many vegetable plantings, citrus groves, and cattle were submerged or drowned as the storm exacerbated already high water levels and briefly threatened to breach the dikes surrounding Lake Okeechobee. However, the dikes held firm, and evacuations were otherwise credited with minimizing the potential death toll. On the west coast of the state, the storm caused further flooding, extensive damage south of the Tampa Bay Area, and the loss of a ship at sea.

On September 18, the hurricane entered the Gulf of Mexico and threatened the Florida Panhandle, but later its track moved farther west than expected, ultimately leading to a landfall southeast of New Orleans, Louisiana. Upon making landfall, the storm killed 34 people on the Gulf Coast of the United States and produced a storm tide as high as 15.2 ft (4.6 m), flooding millions of square miles and destroying thousands of homes. The storm was the first major hurricane to test Greater New Orleans since 1915, and the widespread flooding that resulted spurred flood-protection legislature and an enlarged levee system to safeguard the flood-prone area. In all, the powerful storm killed 51 people and caused $110 million (1947 US$) in damage.[nb 1]

Meteorological history

Hurricane Four was first monitored as an area of low pressure over French West Africa on September 2, 1947. Steadily tracking westward, the system was quickly classified as a depression before moving into the Atlantic Ocean near Dakar, Senegal, on September 4. Shortly thereafter, weather agencies lost track of the system over water due to a lack of ships in the region.[2] However, later analysis determined that the cyclone obtained tropical storm status, with maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (60 km/h), during the morning of September 5.[3] The storm gradually intensified as it tracked nearly due west, but then maintained an intensity of 60 mph (100 km/h) for nearly five days, taking a west-southwest turn on September 7 before turning to the northwest two days later, when the steamship Arakaka provided confirmation of its existence.[2][3] Another few days later, the cyclone began to intensify more rapidly as its forward speed increased; between September 10 and 15, reconnaissance missions by the United States Navy began monitoring the hurricane.[2] At 1500 UTC on September 11, a navy aircraft first penetrated the storm; in less than 24 hours, the storm rapidly strengthened into the equivalence of a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale, and shortly afterward attained peak winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), roughly 18 hours after being classified a tropical storm, as another aircraft registered a barometric pressure of 977 mb (28.84 inHg), a drop of 22 mb in 24 hours.[4] On September 13, another airplane at 1930 UTC confirmed that the storm had deepened further to 952 mb (28.11 inHg) and its eye shrunk to 6 nmi (11 km);[4] by that time the hurricane had reached high-end Category 3 intensity, and intensified into a Category 4 hurricane six hours later.[3] The same mission reported a double eyewall,[5] a feature replaced by a large eye by the time the storm hit the Bahamas and Florida.[4][6] The next day, the storm attained the minimum pressure, 938 mb (27.70 inHg), recorded by aircraft reconnaissance during its life span,[4] peaking in intensity as a strong Category 4 hurricane.[3] On September 15, however, the storm lost this intensity. Early on September 16, as its movement slowed greatly and turned westward near the northern Bahamas, the cyclone weakened into a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 120 mph (190 km/h).[3] Following the phonetic alphabet from World War II,[7] the U.S. Weather Bureau office in Miami, Florida, which then worked in conjunction with the military, named the storm George,[8] though such names were apparently informal and did not appear in public advisories until 1950, when the first Atlantic storm to be so designated was Hurricane Fox.[7]

While retaining its intensity, the storm, its northwesterly course having been blocked by a ridge of high pressure,[9] crossed the northern portion of the Abaco Islands, where on Elbow Cay the Hope Town weather station simultaneously estimated winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and recorded 960.7 mb (28.37 inHg)[10] as the center passed just to the north.[2][4] Until 2014, the cyclone was classified as a Category 5 hurricane in the northern Bahamas, based largely upon the observation from Elbow Cay; however, this wind was eventually determined to be unrepresentative of the intensity.[11] (Visual estimates of wind speed, particularly early in the era of modern reconnaissance, were sometimes unreliable.[12]) About 24 hours later on September 17, it made landfall near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, as a Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds near 130 mph (210 km/h).[3] To this date, the hurricane remains the only major hurricane to have struck Broward County, Florida, at that strength,[3] and the only one to pass directly over the county seat of Fort Lauderdale,[7] though the 1926 Miami hurricane and Hurricane King caused significant damage in the county.[13] About 1700 UTC, the cyclone produced peak gusts of 155 mph (249 km/h) and sustained winds of 122 mph (196 km/h) at Hillsboro Inlet Light near Pompano Beach, Florida;[2][14][15] the gust was the highest measured wind speed recorded in the state of Florida until 1992, when Hurricane Andrew produced a gust of 177 mph (285 km/h) at Perrine.[16][17] The station also reported a pressure of 947.2 mb (27.97 inHg), the lowest during the passage of the storm over Florida,[2][18] though Fort Lauderdale, in the eye to the south, reported higher pressures; winds at the lighthouse briefly lulled as the center passed nearby, while Fort Lauderdale reported a one-hour lull.[11][14] Unusually, the lowest pressures occurred not in the center of the eye, but near its northern edge, suggesting the influence of eyewall mesovortices.[11] The hurricane moved slowly inland near 10 mph (16 km/h),[2] and it diminished to a Category 2 hurricane over the Everglades.[3] Early on September 18, the cyclone entered the Gulf of Mexico near Naples, producing wind gusts of 120 mph (190 km/h) at Sanibel Island Light near Fort Myers.[2]

Once over water, the hurricane had diminished to about 90 mph (140 km/h);[3] though no further reconnaissance missions were dispatched to estimate its intensity over the Gulf of Mexico,[4] it is believed to have begun reintensifying as it turned west-northwest and its forward motion increased to 15 mph (24 km/h).[2][3] On September 19, the hurricane moved ashore over Saint Bernard Parish, Louisiana, as a high-end Category 2 hurricane with sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h).[19] The hurricane quickly weakened as it moved over the New Orleans metropolitan area,[3] although its strong winds gusted to 125 mph (201 km/h) in New Orleans.[20] The eye passed over Baton Rouge, the state capital, between 2000 and 2020 UTC,[20] with anemometers registering sustained winds of 96 mph (154 km/h) at 2045 UTC.[2] On September 20, the storm rapidly weakened to a tropical depression over northeastern Texas, but the remnant circulation turned northeast over southeastern Oklahoma and northwest Arkansas. On September 21, it dissipated over southern Missouri.[3]

Preparations

On the evening of September 15, the U.S. Weather Bureau expected the storm to recurve, precipitating a possible landfall between Jacksonville, Florida, and Savannah, Georgia. As a precautionary measure, small watercraft between Jupiter, Florida, and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, were advised to remain in port.[5] Early on September 16, the forecast was revised, and hurricane warnings were issued for the Florida east coast from Titusville to Fort Lauderdale,[10] later to be expanded to Miami.[21] As the hurricane approached Northern commercial flights were grounded, and 1,500 National Guard troops were readied for mobilization if “deemed necessary” by Florida Governor Millard Caldwell.[21] 4,700 persons in Broward County moved into shelters established by the Red Cross,[6] while up to 15,000 people evacuated the flood-prone Lake Okeechobee region.[22] In all, more than 40,000 people statewide moved into shelters established by the Red Cross.[20] Military aircraft were flown to safer locations, in some cases four days or more in advance.[23] Hotels in the threatened area filled quickly due to fears of a disaster similar to the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane;[22] at Melbourne and Cocoa no vacant hotels were left for evacuees.[5] During the storm, the MacArthur, North Bay (now Kennedy), and Venetian Causeways in Miami were closed to traffic.[24] At Lake Worth alone, 1,800 people sheltered in nine official shelters during the storm.[25]

As the hurricane entered the Gulf of Mexico, initial forecasts expected the storm to strike between Apalachicola and Pensacola, Florida, but by 0415 UTC on September 19, hurricane warnings were issued by the Weather Bureau office in New Orleans covering Saint Marks, Florida, to Morgan City, Louisiana.[26] As the storm neared Louisiana, Emile Verret, the acting governor of Baton Rouge, closed the state capital and sent public officials home. In New Orleans, local National Guard units were mobilized.[27]

Impact

The Bahamas

As the storm passed nearby, Green Turtle Cay was flooded by 2 feet (0.61 m) of water and the local weather station abandoned.[28] Strong winds damaged or destroyed many homes and docks on the western end of Grand Bahama.[29] At Settlement Point, a storm surge of 12 ft (3.7 m) destroyed half the community, preventing medical supplies from being delivered until September 20.[30] Despite its intensity, the storm was not attributed to any known deaths in The Bahamas.[2]

Florida

The storm killed only 17 people in Florida,[17][31] many fewer than the size and intensity of the storm suggested, largely due to improved warnings and preparations, as well as more stringent construction standards,[6] since the 1920s.[17] The hurricane was not only intense and slow-moving, but also unusually large:[17] some reports indicated winds of hurricane force extended 120 mi (190 km) from the center in all directions.[2] Winds of over 50 mph (80 km/h) spread nearly 150 mi (240 km) in all directions, affecting practically the entire Florida peninsula below the latitude of Brevard County.[17] In spite of the winds, wind-caused structural damage was generally minor;[32][33] in Broward County only 37 homes were irreparably destroyed, primarily small homes or those undermined by coastal waves,[33] while in the Palm Beach area most of the unroofed buildings were small and cheaply built; most newer structures, built since the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane, resulted in less damage in the September 1947 storm.[32]

Upon making its first U.S. landfall, the storm produced wind gusts estimated at up to 127 mph (204 km/h) in Fort Lauderdale,[17][18] though estimates varied as other observations elsewhere in South Florida ranged from 140 mph (230 km/h)[34] to 180 mph (290 km/h),[35] and up to 150 mph (240 km/h) in Fort Lauderdale itself.[17] Intense wind gusts unroofed hundreds of homes and apartments in the Hollywood–Fort Lauderdale area, and reportedly “few utility poles were left standing, many having been snapped like toothpicks by the 150 mph (240 km/h) gusts.”[17] At the Boca Raton Army Air Field, the hurricane destroyed 150 barracks, supply houses, warehouses, the post stockade, the fire station, and the theater and mess buildings.[34] Losses as lately reported were 1947 US$4,500,000,[23] hastening existing plans to close the base.[35][36] At West Palm Beach, 40% of the initial 1947 US$1,500,000 in damages was related to roof damage.[32] Farther south, the 11,000-seat Hialeah race track was mostly unroofed, with barns and paddocks damaged and many of its famed flamingos missing.[37]

On the east coast of Florida, many cities experienced significant flooding; tides of up to 11 ft (3.4 m) affected Broward and Palm Beach counties,[17] washing out large portions of State Highway A1A between Palm Beach and Boynton Beach,[38] as well as between Sunny Isles Beach and Haulover.[17] High tides carved a channel 3 ft (0.91 m) deep and rendered a nearby road impassable while nearly reopening New River Inlet, which had silted over and never re-emerged since the 1935 Yankee hurricane.[39] At Miami Beach many of the 334 resort hotels as well as homes and apartments were battered by waves.[37] There, a three-to-four-ft-deep (0.9-to-1.2-m) layer of sand covered many oceanfront grounds, and nearby neighborhoods on the Venetian Islands, like Belle Isle, were flooded to a depth of several feet.[24] As it crossed South Florida at about 10 mph (16 km/h), the storm dropped a prodigious amount of rain over a broad area, peaking at 10.12 in (257 mm) at Saint Lucie Lock.[17] In Miami, the city manager claimed 200 mi (320 km) of city streets were flooded out, while in Miami Springs half the homes were flooded.[17] The town of Davie, having lost 35,000 citrus trees to floodwaters in preceding months,[33] suffered devastating losses to groves and vegetable beds.[40]

On Lake Okeechobee, concerns about disastrous flooding were heightened by memories of the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane on the south shore and of the 1926 Miami hurricane at Moore Haven. During the storm, tides peaked at 13 ft (4.0 m) on the north shore of the lake[41] and 21 ft (6.4 m) on the south shore at Clewiston and Moore Haven, nearly overrunning the Herbert Hoover Dike that surrounded the lake.[17] However, due to revamped improvements in the dike, the storm caused only minor damage, and the dike prevented a repeat of the flooding of 1926 and 1928, in which over 2,500 people drowned.[42] Nevertheless, floodwaters in the Everglades region resulted in significant losses to cattle, and hundreds of small block homes in the agricultural districts were blown off their foundations.[18][33] Much of the marshy country was waterlogged during and after the storm.[43]

On the west coast of the state, the hurricane produced sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) at Naples, but the anemometer was obstructed from measuring the strongest winds. Damage in the Fort Myers–Punta Gorda area was described as being heavy, and the Coast Guard station at Sanibel Island Light was inundated by floodwaters to a depth of 3 ft (0.91 m).[18] Tides at Everglades City peaked at 5.5 ft (1.7 m), forcing residents into attics and flooding local streets.[17] However, the Tampa Bay area, being north of the eye, had less damage due to offshore winds forcing tides below normal.[2] In Fort Myers, hundreds of trees were prostrated and the city left without power.[43] During the storm, two vessels, with a total combined crew of nine people, went missing; as of September 18, contact had been established with the former and the crew declared safe, but the remaining vessel, with a crew of two, had not been accounted for.[44] Additionally, six Cuban schooners carrying 150 crew members in all sheltered off Anclote Key late on September 17 and rode out the storm.[44] However, another Cuban vessel, the Antonio Cerdedo, foundered and sank off Fort Myers with a loss of seven of its crew members.[20]

Gulf Coast of the United States

The center of the storm, estimated at the time to have been 25 mi (40 km) wide,[2] passed directly over the business district of New Orleans[2] between 1530 and 1700 UTC,[27] making the storm the first major hurricane to pass over the city since 1915; no other storm would pass so close to downtown New Orleans until Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[3] Before the eye arrived, wind instruments at Moisant Airport were disabled after just having registered sustained winds of 90 mph (140 km/h). Due to the increasing northerly winds, water overtopped sections of the levees on Lake Pontchartrain, leaving some lakefront streets submerged “waist deep,” above the 3-ft (0.92-m) delimiter.[27] As communications failed during the calm eye, the Weather Bureau office in Fort Worth, Texas, assumed the duties of the New Orleans office by broadcasting advisories to the public.[27] During the eye, atmospheric pressure in New Orleans dropped as low as 968.9 mb (28.61 inHg) by 1649 UTC.[2]

A large part of Greater New Orleans was flooded, with 2 ft (0.61 m) of water shutting down Moisant Field and 6 ft (1.8 m) of water in parts of Jefferson Parish.[8] The storm surge in Louisiana peaked at 9.8–11.2 ft (3.0–3.4 m) at Shell Beach on Lake Borgne—today submerged due to erosion from the construction in 1968 of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet[45]—and at 11.5 ft (3.5 m) in Ostrica.[8][46] The surge overtopped the 9-ft-tall (2.7-m) Orleans Parish seawall, built by the Orleans Levee Board in the 1920s to prevent a repeat of the 1915 hurricane there, and spread water over 9 sq mi (23 km2) of the parish, as far from Lake Pontchartrain as Gentilly Ridge.[47] In Jefferson Parish, 30,000,000 sq mi (78,000,000 km2) were flooded for as long as two weeks.[47] Subsidence settled behind the levees, leaving “topographic bowls” containing up to 6 ft (1.8 m) of water, to be excavated by dredging and pumping the water back into Lake Pontchartrain.[47] Saint Bernard and Plaquemines parishes were also inundated by an 11-ft (3.4-m) storm surge, though mainly sparsely populated areas were affected.[47]

A storm tide of up to 15.2 ft (4.6 m) was reported along the western half of the Mississippi coastline,[2][48] causing heavy damage in Bay St. Louis, Gulfport, and Biloxi. The recorded tides in these communities were the highest ever recorded until Hurricane Camille, a Category 5 hurricane in 1969 and the strongest hurricane to strike the United States with sustained winds of 190 mph (310 km/h),[3] produced tides of up to 21.7 ft (6.6 m).[48] Although the storm had weakened by its second landfall, the hydrology of the region makes it particularly vulnerable to hurricanes. 12 people were killed in Louisiana and 22 in Mississippi.[31] In both states combined, the Red Cross reported that the storm destroyed 1,647 homes and damaged 25,000 others, with the majority, up to 90%, of the destroyed having been due to water.[2] In New Orleans, the storm produced an estimated 1947 USD$100,000,000 worth of damage to the city.[8] Barometric pressures as low as 971.6 mb (28.69 inHg) and sustained winds as high as 96 mph (154 km/h), equivalent to Category 2 intensity, were reported as far inland as Baton Rouge.[2]

Aftermath

In Florida, a federal state of emergency was declared by then-U.S. President Harry S. Truman.[17] The combined flooding from the September hurricane and a later hurricane in October was among the worst in southern Florida's history, even spurring the creation of the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control District along with a plan for new flood-control levees and canals.[6][7][49] In New Orleans, the United States Congress approved the Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity Project to assist ongoing efforts to increase the height of the existing levee along the lakeshore; to bolster the existing seawall in Orleans Parish, an 8-ft-high (2.4-m) levee was erected along lakeside Jefferson Parish.[47]

The storm is most commonly called the 1947 Fort Lauderdale hurricane but is sometimes referred to as Hurricane George, the 1947 New Orleans hurricane, or the 1947 Pompano Beach (or Broward) hurricane.[50][51] If this same storm were to hit today it would probably do around $11.72 billion (2004 US$) in damages.[52]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1947 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- ↑ "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996". NOAA/NHC. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Sumner, H. C. (December 1947). "North Atlantic hurricanes and tropical disturbances of 1947" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 75 (11): 251–55. Bibcode:1947MWRv...75..251S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1947)075<0251:NAHATD>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 U.S. Weather Bureau Microfilm. Miami, FL: National Hurricane Center. September 1947.

- 1 2 3 "Strong Winds Expected Here Today". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. September 16, 1947.

- 1 2 3 4 "Three 1947 Storms Produced Record Rainfall". Miami Herald. September 3, 1978.

- 1 2 3 4 Norcross, Bryan (2007). Hurricane Almanac: The Essential Guide to Storms Past, Present, and Future. St. Martin’s Griffin. ISBN 978-0312371524.

- 1 2 3 4 Roth, David (2010). "Louisiana Hurricane History". NOAA National Weather Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Daily Weather Maps Project". NOAA. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Warnings Issued, Lauderdale to Titusville". Miami Daily News. September 16, 1947. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (March 2014). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT) Meta Data". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Hagen, Andrew B.; Donna Strahan-Sakoskie; Christopher Luckett (2012). "A Reanalysis of the 1944–53 Atlantic Hurricane Seasons—The First Decade of Aircraft Reconnaissance". Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 25 (13): 4441–4460. Bibcode:2012JCli...25.4441H. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00419.1. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Barnes 1998, pp. 193–5

- 1 2 Daily Local Record for Hillsboro Light. Miami, FL: U.S. WBO. September 1947.

- ↑ Heath, Richard C.; et al. "Hydrologic Almanac of Florida" (PDF). Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ↑ Williams, John M.; Iver W. Duedall (1997). "Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms: Revised Edition" (PDF). University Press of Florida. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Barnes 1998, pp. 172–3

- 1 2 3 4 Florida Climatological Data. National Climatic Data Center. 1947.

- ↑ Blake; Rappaport & Landsea (2006). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones (1851 to 2006)" (PDF). NOAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "Severe Local Storms for September 1947" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. U.S. Weather Bureau. 75 (11): 183–84. September 1947. Bibcode:1947MWRv...75..183.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1947)075<0183:SLSFS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Storm Nears Florida: Rich Resort Area Periled". Kingsport News. September 17, 1947.

- 1 2 "Winds Rake Coast in Hurricane Path Nearing Florida". New York Times. September 17, 1947.

- 1 2 "Boca Field Digging Its Way Out". Delray Beach News. September 26, 1947. p. 5.

- 1 2 "Miami: Beach Hard-Hit". Miami Daily News. September 18, 1947. p. 2.

- ↑ "L. W. (Lake Worth) Reports Few Hardships". Palm Beach Post. September 19, 1947. pp. 1, 4.

- ↑ "Storm Heads for Louisiana". Palm Beach Post. September 19, 1947. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hurricane Hits New Orleans". Windsor Daily Star (Ontario, Dominion of Canada). September 19, 1947. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ "Hurricane (Continued From Page 1)". Times Recorder. September 18, 1947.

- ↑ "Assess Atlantic Hurricane Damage". Lethbridge Herald. September 18, 1947.

- ↑ "Coast Guard Cutter Takes Food, Medicine to Bahama Island". The News and Courier (Charleston, SC). September 21, 1947. p. 3.

- 1 2 "NOAA: Gulf Coast hurricanes". Archived from the original on September 23, 2005. Retrieved 29 September 2005.

- 1 2 3 "Loss Reported Many Millions In Palm Beach". Palm Beach Post. September 19, 1947. pp. 1, 4.

- 1 2 3 4 "Broward County Takes Stock of Storm Damage". Fort Lauderdale Daily News. September 22, 1947. p. 12.

- 1 2 "Summary Of Damage From Storm In South Florida". Miami Daily News. September 19, 1947. p. 12.

- 1 2 Ling 2005, p. 179

- ↑ "The History of the Boca Raton Airport". Boca Raton Airport Authority. Archived from the original on January 23, 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Wind-Lashed South Florida Digs Out of Storm's Debris". Miami Daily News. September 18, 1947. p. 1.

- ↑ Kleinberg 2003, pp. 219–20

- ↑ "New River Inlet Nearly Reopened". Fort Lauderdale Daily News. September 18, 1947. p. 1.

- ↑ McIver 1983, p. 137

- ↑ "Glades Come Out of Hurricane With Relatively Small Damage". Palm Beach Post. September 19, 1947. pp. 1, 4.

- ↑ Will, Lawrence E. (1978). Okeechobee Hurricane and the Hoover Dike. Great Outdoors Publishing. ASIN B0006YT5ZG.

- 1 2 "Times Writer Plunges Into Heart of Hurricane, Comes Out With Dramatic Story of 'Big Blow'". Saint Petersburg Times. September 19, 1947. p. 10.

- 1 2 "Coast Guard Searches For Two Boats With Eight Men and One Woman Aboard". Saint Petersburg Times. September 19, 1947. p. 13.

- ↑ Bourne Jr., Joel K (October 2004). "Gone With the Water". National Geographic. 206 (4): 88–105.

- ↑ Yamazaki, Gordon; Shea Penland (2001). "Recent hurricanes producing significant basin damage". In Shea Penland; Andrew Beall; Jeff Waters. Environmental Atlas of the Lake Pontchartrain Basin. New Orleans: Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation. p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Colten 2009, pp. 22–4

- 1 2 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (1970). "Hurricane Camille: 14 - 22 August 1969" (PDF). U.S. Army Engineer Mobile District. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ↑ "Top 10 Weather Events MIAMI-DADE COUNTY". NWS Miami, FL. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ↑ Bush et al., p. 41

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W.; James L. Franklin; Colin J. McAdie; John L. Beven II; James M. Gross; Brian R. Jarvinen; Richard J. Pasch; Edward N. Rappaport; Jason P. Dunion & Peter P. Dodge (November 2004). "A Reanalysis of Hurricane Andrew's Intensity" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. American Meteorological Society. 85 (11): 1699–1712. Bibcode:2004BAMS...85.1699L. doi:10.1175/BAMS-85-11-1699. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "NOAA/NHC costliest US hurricanes (normalized)". Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. Retrieved 5 November 2005.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Jay (1998), Florida's Hurricane History, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-2443-7

- Bryan, Norcross (2007), Hurricane Almanac: The Essential Guide to Storms Past, Present, and Future, St. Martin’s Griffin, ISBN 978-0312371524

- Bush, David M. (2004), Living with Florida's Atlantic Beaches, Duke University Press, ISBN 0822332892

- Churl, Donald W.; Johnson, John P. (1990), Boca Raton: A Pictorial History, The Downing Company Publishers, ISBN 0-89865-792-X

- Colten, Craig C. (2009), Perilous Place, Powerful Storms: Hurricane Protection in Coastal Louisiana, University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 9781604733457

- Duedall, Iver W.; Williams, John M. (2002), Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms, 1871-2001, University Press of Florida, ISBN 978-0813024943

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993), Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events, St. Johnsbury, Vermont: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films, ISBN 1-879362-03-1

- Kleinberg, Elliot (2003), Black Cloud: the Deadly Hurricane of 1928, New York: Carroll & Graf, ISBN 0-7867-1386-0

- Ling, Sally J. (2005), Small Town, Big Secrets: Inside the Boca Raton Army Air Field During World War II, The History Press, ISBN 1-59629-006-4

- McIver, Stuart B. (1983), Fort Lauderdale and Broward County: An Illustrated History, Fort Lauderdale Historical Society, ISBN 978-0897810814

- Lawrence E, Will (1978), Okeechobee Hurricane and the Hoover Dike, Great Outdoors Publishing, ASIN B0006YT5ZG

External links

- The Times-Picayune in 175 years – 1947: New Orleans, Metairie flooded by hurricane

- UNISYS tracks for 1947 storms

- Pictures from Lake Okeechobee area after the storm