1919 Tour de France

| |||

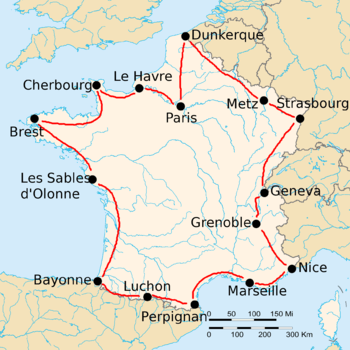

| Route of the 1919 Tour de France Followed counterclockwise, starting in Paris | |||

| Race details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 29 June – 27 July | ||

| Stages | 15 | ||

| Distance | 5,560 km (3,455 mi) | ||

| Winning time | 231h 07' 15" | ||

| Results | |||

| Winner | (Category A) | ||

| Second | (Category A) | ||

| Third | (Category A) | ||

The 1919 Tour de France was the 13th edition of the Tour de France, taking place from 29 June to 27 July over a total distance of 5,560 kilometres (3,450 mi).[1] It was the first Tour de France after World War I, and was won by Firmin Lambot. In the eleventh stage, the yellow jersey, given to the leader of the general classification, was introduced, and first worn by Eugène Christophe.[2]

The fighting in World War I had ravaged the French road system, which made cycling difficult. As a result, the average speed (24.056 km/h) and the number of finishing cyclists (ten) were the lowest in history.[3][4]

Background

Since the previous Tour de France in 1914, it was impossible to organise the Tour de France due to World War I. Tour organiser Henri Desgrange always wanted to organise a new Tour after the war, and within days after the end of the war, the organisation of the 1919 Tour de France started.[5]

Changes from the previous Tour

Three former winners of the Tour, François Faber, Octave Lapize and Lucien Petit-Breton had died fighting in the war. Two other former winners, Philippe Thys and Odile Defraye started the race.[6] The war had been only over for seven months, so most cyclists did not have a chance to train enough for the Tour.[7] For that reason, there were almost no new younger cyclists, and the older cyclists dominated the race.[8] The organisation did not make it easy for the cyclists: with 5560 km it was longer than all the previous Tours, and since then only the 1926 Tour de France has been longer.[4]

The bicycle manufacturers had also suffered from the war, and were unable to sponsor teams of cyclists. They worked together, and sponsored more than half of the cyclists under the name "La Sportive",[9] but effectively all the cyclists rode as individuals.[7] Cyclists were divided in an A-category (professional) and a B-category (amateurs).[6]

In previous years, cyclists had to take care of their own food during the race. In 1919, the tour organisation took care of this.[10]

Participants

Race overview

.jpg)

The first stage was won by Belgian Jean Rossius. However, he was penalized with 30 minutes for illegally helping Philippe Thys, therefore Henri Pélissier was leading the race.[11] It had not helped Thys however, because he had to stop the race in the first stage after a large crash.[7]

In the beginning of the race, Henri and Francis Pélissier were the best. They both finished before the rest in stage two, with Henri crossing the line first. In the third stage, Henri, leading the race, wanted to stop. Organizer Desgrange did all he could to change Pélissier's mind, and finally Pélissier started to race again. He was already 45 minutes behind, and the next three hours he was chasing the rest. He finally caught up, and finished second in the sprint, after his brother Francis.[7] After that victory, Henri Pélissier said that he was a thoroughbred and the rest of the cyclists were work horses, which made the other cyclists angry.[9] During that third stage, Léon Scieur punctured four times, and lost two hours.[12]

In the fourth stage, the rest of the cyclists (only 25 were still in race) took revenge on the Pélissier brothers. When they had to change bicycles, everybody else sped away from them.[7] Henri Pélissier chased the rest, but was then ordered by Desgrange to stop working together with other cyclists in his pursuit. In the end, Henri Pélissier had lost more than 35 minutes, and his brother Francis over three hours. The Pélissier brothers were angry at the organisation and left the race.[9] Jean Alavoine won the stage, and Eugène Christophe became the new leader in the general classification.[6]

Alavoine would also win the fifth stage, the longest ever in history at 482 kilometres (300 mi).[6] Christophe was still in Grenoble at the start of stage eleven, when tour organiser Henri Desgrange gave him a yellow jersey, so that he could easily be recognized.[6] The colour was inspired by the colour of the organizing newspaper l'Auto,[7][13] although another explanation is that other colours were not available in the post-war shortage.[9] Christophe was not happy with his yellow jersey, and other cyclists called him a canary.[9] At that point in the race, it was likely that Christophe would stay the leader until the end of the Tour de France, because he remained in that yellow jersey after the Pyrénées and the Alps. In the penultimate stage, Firmin Lambot, who was in second position, more than 28 minutes behind, attacked. Christophe, still leading the race, chased him, but broke his fork close to Valenciennes.[7] The rules were such that cyclists could get no help at all, so Christophe repaired his bicycle himself. This same thing had already cost him the victory in 1913, and would happen to him for a third time in 1922.[14] It took him over two and a half hours, and he had lost the lead to Lambot. In the last stage, Christophe had a record number of punctures, and also lost his second place to Jean Alavoine.[6] Lambot, aged 33, was at that moment the oldest Tour de France winner in history.[4]

Because the organising newspaper l'Auto felt bad for Christophe, he received the same prize money as the winner Lambot. In addition, a collection raised money, the donors for this prize were reported in 20 pages in the newspaper.[15] Altogether, Christophe received 13310 Francs, much more than the 5000 Francs that Lambot received for his victory.[9]

Results

In each stage, all cyclists started together. The cyclist who reached the finish first, was the winner of the stage. The time that each cyclist required to finish the stage was recorded. For the general classification, these times were added up; the cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader. From the eleventh stage on, the leader in the general classification was identified by the yellow jersey.

Stage winners

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type[n 1] | Winner | Race leader | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 June | Paris to Le Havre | 388 km (241 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 2 | 1 July | Le Havre to Cherbourg | 364 km (226 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 3 | 3 July | Cherbourg to Brest | 405 km (252 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 4 | 5 July | Brest to Les Sables-d'Olonne | 412 km (256 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 5 | 7 July | Les Sables-d'Olonne to Bayonne | 482 km (300 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 6 | 9 July | Bayonne to Luchon | 326 km (203 mi) | | Stage with mountain | | |

| 7 | 11 July | Luchon to Perpignan | 323 km (201 mi) | | Stage with mountain | | |

| 8 | 13 July | Perpignan to Marseille | 370 km (230 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 9 | 15 July | Marseille to Nice | 338 km (210 mi) | | Stage with mountain | | |

| 10 | 17 July | Nice to Grenoble | 333 km (207 mi) | | Stage with mountain | | |

| 11 | 19 July | Grenoble to Geneva | 325 km (202 mi) | | Stage with mountain | | |

| 12 | 21 July | Geneva to Strasbourg | 371 km (231 mi) | | Stage with mountain | | |

| 13 | 23 July | Strasbourg to Metz | 315 km (196 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 14 | 25 July | Metz to Dunkerque | 468 km (291 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| 15 | 27 July | Dunkerque to Paris | 340 km (210 mi) | | Plain stage | | |

| Total | 5,560 km (3,455 mi)[1] | ||||||

General classification

Of the 67 cyclists that started the race, only 11 cyclists finished. On 12 August 1919, Paul Duboc (8th overall), was disqualified for borrowing a car to go and repair his pedal axle, which left only 10 cyclists in the final classification. In total, 43 cyclists started as category A, and 24 cyclists as category B.[10]

| Rank | Rider | Category | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | | A | 231h 07' 15" |

| 2 | | A | + 1h 42' 54" |

| 3 | | A | + 2h 26' 31" |

| 4 | | A | + 2h 52' 15" |

| 5 | | A | + 4h 14' 22" |

| 6 | | A | + 15h 21' 34" |

| 7 | | A | + 16h 01' 12" |

| 8 | | A | + 18h 23' 02" |

| 9 | | A | + 20h 29' 01" |

| 10 | | B | + 21h 44' 12" |

Aftermath

The yellow jersey that was introduced in this tour, was so successful that it has been used ever since. The winner of the race, Lambot, would later also win the 1922 Tour de France, but has become a half-forgotten figure in the Tour's history. Christophe, who lost the Tour due to bad luck, is still remembered as an eternal second.[6]

The fight between cyclist Pélissier and tour organizer Desgrange would continue for many years. Pélissier would win the 1923 Tour de France.

Notes and references

Footnotes

References

- 1 2 Historical guide 2016, p. 108.

- ↑ "The Tour - Year 1919". Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ↑ "Tour de France Statistics". Bike Race Info. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Le Tour en chiffres - Le palmarès" (PDF) (in French). ASO. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ↑ Barry Boys. "THE RETURN of a Grand Affair - "New Tour Legend: the Maillot Jaune"". Cycling Revealed. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tom James (15 August 2003). "1919: Christophe in Yellow - but not in Paris". Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "1919: Wanhoopspoging levert Firmin Lambot Tourzege op" (in Dutch). Tourdefrance.nl. 19 March 2003. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ↑ "Tour de France: Timeline". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France. Dog Ear Publishing. pp. 51–56. ISBN 1-59858-180-5. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "13ème Tour de France 1919" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ↑ "13ème Tour de France 1919 - 1ème étape" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Tom James (15 August 2003). "1921: Scieur continues the Belgian domination". Veloarchive. Archived from the original on 2009-06-10. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ↑ "Le premier Maillot Jaune - Tour de France 1919" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ "1919-1929: 'Convicts of the road'". BBC Sport. 5 June 2001. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ↑ Woodland, Les (2007). The Yellow Jersey Guide to the Tour de France. Yellow Jersey, UK. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-224-08016-3.

- ↑ Historical guide 2016, p. 17.

- ↑ Arian Zwegers. "Tour de France GC Top Ten". CVCC. Archived from the original on 2009-06-06. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

Sources

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

External links

![]() Media related to 1919 Tour de France at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1919 Tour de France at Wikimedia Commons