1840s

| Millennium: | 2nd millennium |

| Centuries: | 18th century – 19th century – 20th century |

| Decades: | 1810s 1820s 1830s – 1840s – 1850s 1860s 1870s |

| Years: | 1840 1841 1842 1843 1844 1845 1846 1847 1848 1849 |

| 1840s-related categories: |

Births – Deaths – By country Establishments – Disestablishments |

The 1840s decade ran from January 1, 1840, to December 31, 1849.

Politics and wars

Pacific Islands

In 1842, Tahiti and Tahuata were declared a French protectorate, to allow Catholic missionaries to work undisturbed. The capital of Papeetē was founded in 1843. In 1845, George Tupou I united Tonga into a kingdom, and reigned as Tuʻi Kanokupolu.

East Asia

China

On August 29, 1842, the first of two Opium Wars ended between China and Britain with the Treaty of Nanking. One of the consequences was the cession of modern-day Hong Kong Island to the British. Hong Kong would eventually be returned to China in 1997.

Other events:

- July 3, 1844 – The United States signs the Treaty of Wanghia with the Chinese Government, the first ever diplomatic agreement between China and the United States.

Japan

The 1840s comprised the end of the Tenpō era (1830-1844), the entirety of the Kōka era (1844-1848), and the beginning of the Kaei era (1848-1854). The decade saw the end of the reign of Emperor Ninko in 1846, who was succeeded by his son, Emperor Kōmei.

Southeastern Asia

Vietnam

Emperors Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị and Tự Đức ruled Vietnam during the 1840s under the Nguyễn dynasty.

New Guinea

- 1848 – British, Dutch, and German governments lay claim to New Guinea.

Australia and New Zealand

- First signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) on February 6, 1840, at Waitangi, Northland New Zealand. The treaty between the British Crown and Māori made New Zealand colony and is considered the founding point of modern New Zealand.

- July 20, 1845 – Charles Sturt enters the Simpson Desert in central Australia.

- May 25, 1846 – The Royal Geographical Society awards Paweł Edmund Strzelecki a Gold Medal "for exploration in the south eastern portion of Australia".

- June 15, 1846 – Launceston Church Grammar School opens for the first time in Tasmania

Southern Asia

Afghanistan

The First Anglo-Afghan War had started in 1838, started by the British as a means of defending India (under British control at the time) from the Russian Empire's expansion into Central Asia.[1] The British attempted to impose a puppet regime on Afghanistan under Shuja Shah, but the regime was short lived and proved unsustainable without British military support. By 1842, mobs were attacking the British on the streets of Kabul and the British garrison was forced to abandon the city due to constant civilian attacks. During the retreat from Kabul, the British army of approximately 4,500 troops (of which only 690 were European) and 12,000 camp followers was subjected to a series of attacks by Afghan warriors. All of the British soldiers were killed except for one and he and a few surviving Indian soldiers made it to the fort at Jalalabad shortly after.[2] After the Battle of Kabul (1842), Britain placed Dost Mohammad Khan back into power (1842-1863) and withdrew from Afghanistan.

India

- March 24, 1843 – Battle of Hyderabad: The Bombay Army led by Major General Sir Charles Napier defeats the Talpur Emirs, securing Sindh as a Province of British India.

Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was founded in 1799, ruled by Ranjit Singh. When Singh died in 1839, the Sikh Empire began to fall into disorder. There was a succession of short-lived rulers at the central Durbar (court), and increasing tension between the Khalsa (the Sikh Army) and the Durbar. In May 1841, the Dogra dynasty (a vassal of the Sikh Empire) invaded western Tibet,[3] marking the beginning of the Sino-Sikh war. This war ended in a stalemate in September 1842, with the Treaty of Chushul.

The British East India Company began to build up its military strength on the borders of the Punjab. Eventually, the increasing tension goaded the Khalsa to invade British territory, under weak and possibly treacherous leaders. The hard-fought First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-1846) ended in defeat for the Khalsa. With the Treaty of Lahore,[4] the Sikh Empire ceded Kashmir to the East India Company and surrendered the Koh-i-Noor diamond to Queen Victoria.

The Sikh empire was finally dissolved at the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849 into separate princely states and the British province of Punjab. Eventually, a Lieutenant Governorship was formed in Lahore as a direct representative of the British Crown.

Sri Lanka

- July 26, 1848 – Matale Rebellion against British rule in Sri Lanka.

Western Asia

Ottoman Empire

The decade was near the beginning of the Tanzimât Era of the Ottoman Empire. Sultan Abdülmecid I ruled during this period.

Lebanon

Emir Bashir Shihab II controlled the Mount Lebanon Emirate at the beginning of the 1840s. Bashir allied with Muhammad Ali of Egypt, but Muhammad Ali was driven out of the country. Bashir was deposed in 1840 when the Egyptians were driven out by an Ottoman-European alliance, which had the backing of Maronite forces. His successor, Emir Bashir III, ruled until 1842, after which the emirate was dissolved and split into a Druze sector and a Christian sector.

Romania

- June 21, 1848 – Wallachian Revolution of 1848: The Proclamation of Islaz is made public and a Romanian revolutionary government led by Ion Heliade Rădulescu and Christian Tell is created.

Persian Empire

- 1847 – The Ottoman Empire cedes Abadan Island to the Persian Empire.

Revolutions of 1848

There was a wave of revolutions in Europe, collectively known as the Revolutions of 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, but within a year, reactionary forces had regained control, and the revolutions collapsed.

The revolutions were essentially bourgeois-democratic in nature with the aim of removing the old feudal structures and the creation of independent national states. The revolutionary wave began in France in February, and immediately spread to most of Europe and parts of Latin America. Over 50 countries were affected, but with no coordination or cooperation among the revolutionaries in different countries. Six factors were involved: widespread dissatisfaction with political leadership; demands for more participation in government and democracy; demands for freedom of press; the demands of the working classes; the upsurge of nationalism; and finally, the regrouping of the reactionary forces based on the royalty, the aristocracy, the army, and the peasants.[5]

The uprisings were led by ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more forced into exile. The only significant lasting reforms were the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the definitive end of the Capetian monarchy in France. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire, but did not reach Russia, Sweden, Great Britain, and most of southern Europe (Spain, Serbia,[6] Greece, Montenegro, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire).[7]

Eastern Europe

Russia

- May 22, 1841 – The Georgian province of Guria revolts against the Russian Empire.

- 1848 – Admiral Nevelskoi explores the Strait of Tartary.

- November 16, 1849 – A Russian court sentences Fyodor Dostoevsky to death for anti-government activities linked to a radical intellectual group, the Petrashevsky Circle. Facing a firing squad on December 23 the group members are reprieved at the last moment and exiled to the katorga prison camps in Siberia.

Austrian Empire

- June 2–12, 1848 – Prague Slavic Congress brings together members of the Pan-Slavism movement.

Hungary

- March 15, 1848 – Start of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

- May 15, 1848 – 40,000 Romanians meet at the Blaj to protest Transylvania becoming a part of Hungary.[8]

- October 6, 1849 – The 13 Martyrs of Arad are executed after the Hungarian War of Independence.

Galicia

- February 18, 1846 – Beginning of the Galician peasant revolt.

Northern Europe

Sweden

- 1842 – Compulsory elementary education introduced.

- March 8, 1844 – King Oscar I ascends to the throne of Sweden-Norway upon the death of his father Charles XVI/III John.

Denmark

- 1843 – The Danish government re-establishes the Althing in Iceland as an advisory body.

- March 24, 1848 – Start of the First Schleswig War (German: Schleswig-Holsteinischer Krieg or Three Years' War (Danish: Treårskrigen)). The First Schleswig War was the first round of military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig-Holstein Question, contesting the issue of who should control the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. The war, which lasted from 1848 to 1851, also involved troops from Prussia and Sweden. Ultimately, the war resulted in a Danish victory. A second conflict, the Second Schleswig War, erupted in 1864.

- June 5, 1849 – Denmark becomes a constitutional monarchy.

United Kingdom

- September 16, 1840 – Joseph Strutt hands over the deeds and papers concerning the Derby Arboretum, which is to become England's first public park.

- August 10, 1842 – The Mines Act 1842 becomes law, prohibiting underground work for all women and boys under 10 years old in England.

- March 25, 1843 – Marc Isambard Brunel's Thames Tunnel, the first tunnel under the River Thames and the world's first bored underwater tunnel, is opened in London.[4]

- May 4, 1843 – Natal is proclaimed a British colony.

- April – The Fleet Prison for debtors in London is closed.

- July, 1848 – Public Health Act establishes Boards of Health across England and Wales, the nation's first public health law, giving cities broad authority to build modern sanitary systems.[10]

Royalty

Queen Victoria was on the throne 20 June 1837 until her death 22 January, 1901.

Ireland

The Great Famine of the 1840s caused the deaths of one million Irish people and over a million more emigrated to escape it.[11] It is sometimes referred to, mostly outside Ireland, as the "Irish Potato Famine" because one-third of the population was then solely reliant on this cheap crop for a number of historical reasons.[12][13][14] The proximate cause of famine was a potato disease commonly known as potato blight.[15] A census taken in 1841 revealed a population of slightly over 8 million.[16] A census immediately after the famine in 1851 counted 6,552,385, a drop of almost 1.5 million in 10 years.[17]

The period of the potato blight in Ireland from 1845 to 1851 was full of political confrontation.[18] A more radical Young Ireland group seceded from the Repeal movement and attempted an armed rebellion in the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, which was unsuccessful.

Western Europe

Germany

- May 18, 1848 – The first German National Assembly (Nationalversammlung) opens in Frankfurt, Germany.

- March – The Frankfurt Parliament completes its drafting of a liberal constitution and elects Frederick William IV emperor of the new German national state.

- April 2, 1849 – Revolutions of 1848 in the German states end in failure.

- May 3, 1849 – The May Uprising in Dresden, last of the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, begins.

Switzerland

- November 3–29, 1847 – Sonderbund War, a civil war in Switzerland in which General Guillaume-Henri Dufour's federal army defeats the Sonderbund (an alliance of seven Catholic cantons) with a total of only 86 deaths.

- September 12, 1848 – One of the successes of the Revolutions of 1848, the Swiss Federal Constitution, patterned on the US Constitution, enters into force, creating a federal republic and one of the first modern democratic states in Europe.

The Netherlands

- October 7, 1840 – Willem II becomes King of the Netherlands.

- November 3, 1848 – A greatly revised Dutch constitution is proclaimed.

France

- March 1, 1840 – Adolphe Thiers becomes prime minister of France.

- September 30, 1840 – The frigate Belle-Poule arrives in Cherbourg, bringing back the remains of Napoléon from Saint Helena to France. He is buried in the Invalides.

- December 15, 1840 – The corpse of Napoleon is placed in the Hotel des Invalides in Paris.

- February 23, 1848 – François Guizot, Prime Minister of France, resigns. 52 people from the Paris mob are killed by soldiers guarding public buildings.

- February 24, 1848 – Louis Philippe, King of the French, abdicates in favour of his grandson, Philippe, comte de Paris, and flees to England after days of revolution in Paris. The French Second Republic is later proclaimed by Alphonse de Lamartine in the name of the provisional government elected by the Chamber under the pressure of the mob.

- May 15, 1848 – Radicals invade the French Chamber of Deputies.

- June 22, 1848 – The French government dissolves the national workshops in Paris, giving the workers the choice of joining the army or going to workshops in the provinces.

- August 28, 1848 – Mathieu Luis becomes the first black member to join the French Parliament as a representative of Guadaloupe.

- November 4, 1848 – France ratifies a new constitution. The Second Republic of France is set up, ending the state of temporary government lasting since the Revolution of 1848.

- December 10, 1848 – Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte is elected first president of the French Second Republic.

- December 20, 1848 – President Bonaparte takes his Oath of Office in front of the French National Assembly.

- January 1, 1849 – France issues Ceres, the nation's first postage stamp.

Southern Europe

Greece

- September 3, 1843 – Popular uprising in Athens, Greece, including citizens and military captains, to require from King Otto the issue of a liberal Constitution to the state, which has been governed since independence (1830) by various domestic and foreign business interests.

Italian Peninsula

- January 12, 1848 – The Palermo rising erupts in Sicily, against the Bourbon kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

- March 22, 1848 – Republic of San Marco comes into existence in Venice.

- January 21, 1849 – General elections are held in the Papal States.

- February 8, 1849 – The new Roman Republic is proclaimed.

- April 27, 1849 – Giuseppe Garibaldi enters Rome to defend it from the French troops of General Oudinot.

- May 15, 1849 – Troops of the Two Sicilies take Palermo and crush the republican government of Sicily.

- July 3, 1849 – French troops occupy Rome; the Roman Republic surrenders.

Spain

- September – The Second Carlist War, or the War of the Matiners or Madrugadores begins in Spain.

- May – The Second Carlist War ends in Spain.

Portugal

- May 16, 1846 – Revolutionary insurrection in Portugal (crushed by royalist troops on February 22, 1847)

Africa

- December 7, 1840 – David Livingstone leaves Britain for Africa.

- August 10, 1845 – The French Consul in Zanzibar (M. Broquant) receives the final letter sent by Eugène Maizan during his expedition into tropical Africa.[19]

- December 20, 1848 – Slavery is abolished on the island of Réunion.

Algeria

- December 21, 1847 – Abd al-Kader surrenders and is imprisoned by the French.

Ethiopia

- February 7, 1842 – Battle of Debre Tabor: Ras Ali Alula, Regent of the Emperor of Ethiopia, defeats warlord Wube Haile Maryam of Semien.

South Africa

- June 4, 1842 – In South Africa, hunter Dick King rides into a British military base in Grahamstown to warn that the Boers have besieged Durban (he had left 11 days earlier). The British army dispatches a relief force.

- December 13, 1843 – Basutoland becomes a British protectorate.[20]

Morocco

- August 14, 1844 – Abdelkader El Djezairi is defeated at Isly in Morocco; the sultan of Morocco soon repudiates his ally.

Liberia

- July 26, 1847 – Liberia gains independence.

- January 3, 1848 – Joseph Jenkins Roberts is sworn in as the first president of the independent African Republic of Liberia.

North America

Canada

In the prior decade, the desire for responsible government resulted in the abortive Rebellions of 1837. The Durham Report subsequently recommended responsible government and the assimilation of French Canadians into English culture.[21] The Act of Union 1840 merged the Canadas into a united Province of Canada and responsible government was established for all British North American provinces by 1849.[22] The signing of the Oregon Treaty by Britain and the United States in 1846 ended the Oregon boundary dispute, extending the border westward along the 49th parallel. This paved the way for British colonies on Vancouver Island (1849) and in British Columbia (1858).[23]

- March 11, 1848 – Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin became the first Joint Premiers of the Province of Canada to be democratically elected under a system of responsible government.

- April 25, 1849 – James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, the Governor General of Canada, signs the Rebellion Losses Bill, outraging Montreal's English population and triggering the Montreal Riots.

United States

- January 18, 1840 – The Electro-Magnetic and Mechanics Intelligencer was the first newspaper in American that used electricity for power of the press to print it.

- February 18, 1841 – The first ongoing filibuster in the United States Senate begins and lasts until March 11.

- May 11, 1841 – Lt. Charles Wilkes lands at Fort Nisqually in Puget Sound.

- August 16, 1841 – U.S. President John Tyler vetoes a bill which called for the re-establishment of the Second Bank of the United States. Enraged Whig Party members riot outside the White House in the most violent demonstration on White House grounds in U.S. history.

- March – Commonwealth v. Hunt: the Massachusetts Supreme Court makes strikes and unions legal in the United States.

- May 19, 1842 – Dorr Rebellion: Militiamen supporting Thomas Wilson Dorr attack the arsenal in Providence, Rhode Island, but are repulsed.

- August 4, 1842 – The Armed Occupation Act is signed, providing for the armed occupation and settlement of the unsettled part of the Peninsula of East Florida.

- August 9, 1842 – The Webster–Ashburton Treaty is signed, settling the dispute over the location of the Maine–New Brunswick border between the United States and Canada, and establishing the United States–Canada border east of the Rocky Mountains.

- May 22, 1843 – The first major wagon train headed for the American Northwest sets out with one thousand pioneers from Elm Grove, Missouri, on the Oregon Trail.

- January 23, 1845 – The United States Congress establishes a uniform date for federal elections, which will henceforth be held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

- March 3, 1845 – Florida is admitted as the 27th U.S. state.

- March 4, 1845 – The United States Congress passes legislation overriding a presidential veto for the first time.

- December 2, 1845 – Manifest destiny: U.S. President James K. Polk announces to Congress that the Monroe Doctrine should be strictly enforced and that the United States should aggressively expand into the West.

- February 26, 1846 – The Liberty Bell is cracked while being rung for George Washington's birthday.

- June 15, 1846 – The Oregon Treaty establishes the 49th parallel as the border between the United States and Canada, from the Rocky Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

- December 28, 1846 – Iowa is admitted as the 29th U.S. state.

- 1846 – The portion of the District of Columbia that was ceded by Virginia in 1790 is re-ceded to Virginia.

- March 1, 1847 – The state of Michigan formally abolishes the death penalty.

- March 4, 1847 – The 30th United States Congress is sworn into office.

- July 1, 1847 – The United States issues its first postage stamps (pictured).

- July 24, 1847 – After 17 months of travel, Brigham Young leads 148 Mormon pioneers into Salt Lake Valley, resulting in the establishment of Salt Lake City.

- January 31, 1848 – Construction of the Washington Monument begins in Washington, D.C.

- May 29, 1848 – Wisconsin is admitted as the 30th U.S. state.

- 1848 – The Illinois and Michigan Canal is completed.

- March 3, 1849 – Minnesota becomes a United States territory.

- March 3, 1849 – The United States Congress passes the Gold Coinage Act allowing the minting of gold coins.

Slavery

- 1840 – United States Census Bureau reports 6,000 free Negroes holding slaves in the nation.

- March 9, 1841 – Amistad: The Supreme Court of the United States rules in the case that the Africans who seized control of the ship had been taken into slavery illegally.

- August 11 (Wednesday) Frederick Douglass spoke in front of the Anti-Slavery Convention in Nantucket, Massachusetts.

- May – Frederick Douglass's Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave written by himself is published by the Boston Anti-Slavery Society.

Native Americans

Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce was predicted to have been born in the 1840s

Presidents

The United States had five different Presidents during the decade. Only the 1880s would have as many. Martin Van Buren was President when the decade began, but was defeated by William Henry Harrison in the U.S. presidential election of 1840. Harrison's service was the shortest in history, starting with his inauguration on March 4, 1841, and ending when he died on April 4, 1841.

Harrison's vice president, John Tyler, replaced him as President (the first Presidential succession in U.S. history), and served out the rest of his term. Tyler spent much of his term in conflict with the Whig party. He ended his term having made an alliance with the Democrats, endorsing James K. Polk and signing the resolution to annex Texas into the United States.

In the Presidential election of 1844, James K. Polk defeated Henry Clay. During his presidency, Polk oversaw the U.S. victory in the Mexican–American War and subsequent annexation of what is now the southwest United States. He also negotiated a split of the Oregon Territory with Great Britain.

In the U.S. presidential election of 1848, Whig Zachary Taylor of Louisiana defeated Democrat Lewis Cass of Michigan. Taylor's term in office was cut short by his death in 1850.

California

- January 16, 1847 – John C. Frémont is appointed Governor of the new California Territory.

- January 30, 1847 – Yerba Buena, California, is renamed San Francisco.

- February 5, 1847 – A rescue effort, called the First Relief, leaves Johnson's Ranch to save the ill-fated Donner Party. These California bound emigrants became snowbound in the Sierra Nevada in the winter of 1846–1847, and some had resorted to cannibalism to survive.

- January 24, 1848 – California Gold Rush: James W. Marshall finds gold at Sutter's Mill, in Coloma, California.

- August 19, 1848 – California Gold Rush: The New York Herald breaks the news to the East Coast of the United States that there is a gold rush in California (although the rush started in January).

- February 28, 1849 – Regular steamboat service from the west to the east coast of the United States begins with the arrival of the SS California in San Francisco Bay. The California leaves New York Harbor on October 6, 1848, rounds Cape Horn at the tip of South America, and arrives at San Francisco after the 4-month-21-day journey.

- November 13, 1849 – The Constitution of California is ratified in a general election.

Texas

- November – The city of Dallas, Texas, is founded by John Neely Bryan.[24]

- February 28, 1845 – The United States Congress approves the annexation of Texas.

- March 1, 1845 – President John Tyler signs a bill authorizing the United States to annex the Republic of Texas.

- July 4, 1845 – Delegates meet in Austin, Texas, to create a state constitution.

- October 13, 1845 – A majority of voters in the Republic of Texas approve a proposed constitution, that if accepted by the United States Congress, will make Texas a U.S. state.

- December 27, 1845 – American newspaper editor John L. O'Sullivan claims (in connection with the annexation of Texas) in The United States Magazine and Democratic Review that the United States should be allowed "the fullfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions". It is the second time he uses the term manifest destiny and will have a huge influence on American imperialism in the following century.

- December 29, 1845 – Texas is admitted as the 28th U.S. state.

- February 19, 1846 – The newly formed Texas state government is officially installed in Austin.

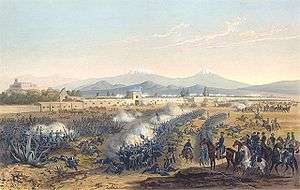

Mexican–American War

In 1845, the United States of America annexed Texas, which had won independence from Centralist Republic of Mexico in the Texas Revolution of 1836. Nevertheless, Mexico still considered Texas part of its territory, declaring war on the U.S., and starting the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).

Combat operations lasted a year and a half, from the spring of 1846 to the fall of 1847. American forces quickly occupied New Mexico and California, then invaded parts of Northeastern Mexico and Northwest Mexico; meanwhile, the Pacific Squadron conducted a blockade, and took control of several garrisons on the Pacific coast farther south in Baja California Territory. Another American army captured Mexico City, and the war ended in a victory for the United States.

American territorial expansion to the Pacific coast was a major goal of U.S. President James K. Polk.[25] Thus, in the war-ending Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the U.S. forced Mexican Cession of the territories of Alta California and New Mexico to the United States in exchange for $15 million, In addition, the United States assumed $3.25 million of debt owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico accepted the loss of Texas and thereafter cited the Rio Grande as its national border.

Mexico

- 1845 – The Republic of Yucatán separates for a second time from Mexico.

- August 17, 1848 – Yucatán officially unites with Mexico.

- 1848 – The Independent Republic of Yucatán joins Mexico in exchange for Mexican help in suppressing a revolt by the indigenous Maya population.

El Salvador

- February – El Salvador proclaims itself an independent republic, bringing an end to the (already de facto defunct) Federal Republic of Central America.

Caribbean

Barbados

- June 6, 1843 – In Barbados, Samuel Jackman Prescod is the first non-white person elected to the House of Assembly.

Dominican Republic

- February 27, 1844 – The Dominican Republic gains independence from Haiti.

- November 6, 1844 – The Dominican Republic drafts its first Constitution.

Haiti

- March 1, 1847 – Faustin Soulouque declares himself Emperor of Haiti.

Trinidad

- May 30, 1845 – Fatel Razack (Fath Al Razack, "Victory of Allah the Provider", Arabic: قتح الرزاق) is the first ship to bring indentured labourers from India to Trinidad, landing in the Gulf of Paria with 227 immigrants.[26]

South America

Brazil

- July 23, 1840 – Pedro II is declared "of age" prematurely and begins to reassert central control in Brazil.

- July 18, 1841 – Coronation ceremony of Emperor Pedro II of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro.

- January 20, 1843 – Honório Hermeto Carneiro Leão, Marquis of Paraná, becomes de facto first prime minister of the Empire of Brazil.

- September 4, 1843 – The Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil marries Dona Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies in a state ceremony in Rio de Janeiro Cathedral.

Uruguay

- February 3, 1843 – Argentina supports Rosas of Uruguay and begins a siege of Montevideo.

Paraguay

- 1844 – Carlos Antonio López becomes dictator of Paraguay.

Argentina

- September 18, 1845 – Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata formally declared.

- November 20, 1845 – Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata: Battle of Vuelta de Obligado: The Argentine Confederation is narrowly defeated by an Anglo-French fleet on the waters of the Paraná River but Argentina attracts political support in South America.

Venezuela

- 1843 – Germans from the Black Forest region of Southern Baden migrate to Venezuela.

Peru

- April 20, 1845 – Ramón Castilla becomes president of Peru.

Chile

- May 23, 1843 – Chile takes possession of the Strait of Magellan.

Science and Technology

Astronomy

- April – Eta Carinae is temporarily the second-brightest star in the night sky.

- September 23, 1846 – Discovery of Neptune: The planet is observed for the first time by German astronomers Johann Gottfried Galle and Heinrich Louis d'Arrest as predicted by the British astronomer John Couch Adams and the French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier.

- September 16, 1848 – William Cranch Bond and William Lassell discover Hyperion, Saturn's moon.

Photography

The 1840s saw the rise of the Daguerreotype. Introduced in 1839, the Daguerreotype was the first publicly announced photographic process and came into widespread use in the 1840s. Numerous events in the 1840s were captured by photography for the first time with the use of the Daguerreotype. A number of daguerrotypes were taken of the occupation of Saltillo during the Mexican–American War, in 1847 by an unknown photographer. These photographs stand as the first ever photos of warfare in history.

Telegraph

- The first electrical telegraph sent by Samuel Morse on May 24, 1844, from Baltimore to Washington, D.C..

Computers

- 1843 – Ada Lovelace translates and expands Menabrea's notes on Charles Babbage's analytical engine, including an algorithm for calculating a sequence of Bernoulli numbers, regarded as the world's first computer program.[27][28][29]

Chemistry

- June 15, 1844 – Charles Goodyear receives a patent for vulcanization, a process to strengthen rubber.

- 1844 – Swedish chemistry professor Gustaf Erik Pasch invents the safety match.

- 1846 – Abraham Pineo Gesner develops a process to refine a liquid fuel, which he calls kerosene, from coal, bitumen or oil shale.

- 1844 John Dalton Dies

Geology

- 1840 – Louis Agassiz publishes his Etudes sur les glaciers ("Study on Glaciers", 2 volumes), the first major scientific work to propose that the Earth has seen an ice age.

Physics

- 1840 – The first English translation of Goethe's Theory of Colours by Charles Eastlake is published.

- 1842 – Julius Robert von Mayer proposes that work and heat are equivalent.[30]

- October 16, 1843 – William Rowan Hamilton discovers the calculus of quaternions and deduces that they are non-commutative.[31]

- 1843 – James Joule experimentally finds the mechanical equivalent of heat.[32]

Biology

- July 3, 1844 – The last definitely recorded pair of great auks are killed on the Icelandic island of Eldey.

- 1844 – The anonymously written Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation is published and paves the way for the acceptance of Darwin's book The Origin of Species.

Paleontology

- 1842 – English palaeontologist Richard Owen coins the name Dinosauria, hence the Anglicized dinosaur.[33]

Psychology

- November 13, 1841 – Scottish surgeon James Braid first sees a demonstration of animal magnetism by Charles Lafontaine in Manchester, which leads to his study of the phenomenon that he (Braid) eventually calls hypnotism.

Economics

- June 20, 1842 – Anselmo de Andrade, Portuguese economist and politician, is born in Vila Real de Santo António.

- August 28, 1844 – Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx meet in Paris, France.

- 1845 – Friedrich Engels' treatise The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 is published in Leipzig as Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England.

- June 1, 1847 – The first congress of the Communist League is held in London.

- February 21, 1848 – Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels publish The Communist Manifesto (Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei) in London.

Medicine

- March 30, 1842 – Anesthesia is used for the first time in an operation (Dr. Crawford Long performed the operation using ether).

- December 27, 1845 – Anesthesia is used for childbirth for the first time (Dr. Crawford Long in Jefferson, Georgia).

- November 4–8, 1847 – James Young Simpson discovers the anesthetic properties of chloroform and first uses it, successfully, on a patient, in an obstetric case in Edinburgh.[34][35]

- January 23, 1849 – Elizabeth Blackwell is awarded her M.D. by the Medical Institute of Geneva, New York, thus becoming the United States' first woman doctor.

Exploration

Antarctica

- January 19, 1840 – Captain Charles Wilkes' United States Exploring Expedition sights what becomes known as Wilkes Land in the southeast quadrant of Antarctica, claiming it for the United States and providing evidence that Antarctica is a complete continent.[36]

- January 21, 1840 – Dumont D'Urville discovers Adélie Land in Antarctica, claiming it for France.[37]

- January 27, 1841 – The active volcano Mount Erebus in Antarctica is discovered and named by James Clark Ross.[38]

- January 28, 1841 – Ross discovers the "Victoria Barrier", later known as the Ross Ice Shelf. On the same voyage, he discovers the Ross Sea, Victoria Land and Mount Terror.

- January 23, 1842 – Antarctic explorer James Clark Ross, charting the eastern side of James Ross Island, reaches a Farthest South of 78°09'30"S.[39]

- January 6, 1843 – Antarctic explorer James Clark Ross discovers Snow Hill Island.

Transportation

Rail

Widespread interest to invest in rail technology led to a speculative frenzy in Britain, known there as Railway Mania. It reached its zenith in 1846, when no fewer than 272 Acts of Parliament were passed, setting up new railway companies, and the proposed routes totalled 9,500 miles (15,300 km) of new railway. Around a third of the railways authorised were never built – the company either collapsed due to poor financial planning, was bought out by a larger competitor before it could build its line, or turned out to be a fraudulent enterprise to channel investors' money into another business.

Steam power

- July 4, 1840 – The Cunard Line's 700-ton wooden paddlewheel steamer RMS Britannia departs from Liverpool, bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the first steam transatlantic passenger mail service.[40]

- July 19, 1843 – Isambard Kingdom Brunel's SS Great Britain is launched from Bristol; it will be the first iron-hulled, propeller-driven ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean.[41]

- 1843 – The steam powered rotary printing press is invented by Richard March Hoe in the United States.[42]

- July 26–August 10, 1845 – Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s iron steamship Great Britain makes the Transatlantic Crossing from Liverpool to New York, the first screw propelled vessel to make the passage.[43][44]

Other inventions

- October 5, 1842 – Josef Groll brews the first pilsner beer in the city of Pilsen, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic).

- September 10, 1846 – Elias Howe is awarded the first United States patent for a sewing machine using a lockstitch design.[45]

Commerce

- In the mid-1840s several harvests failed across Europe, which caused famines. Especially the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849) was severe and caused a quarter of Ireland's population to die or immigrate to the United States, Canada and Australia.

- The Panic of 1837 triggered by the failing banks in America is followed by a severe depression lasting until 1845.

- May 6, 1840 – The Penny Black, the world's first postage stamp, becomes valid for the pre-payment of postage.

- August 10, 1840 – Fortsas hoax: A number of book collectors gather in Binche, Belgium, to attend a non-existent book auction of the late "Count of Fortsas".

- December – The world's first Christmas cards, commissioned by Sir Henry Cole in London from the artist John Callcott Horsley, are sent.[46]

- 1843 – The export of British textile machinery and other equipment is allowed.

- 1844 – Annual British iron production reaches 3 million tons.

- January 4, 1847 – Samuel Colt sells his first revolver pistol to the U.S government.

- The California Gold Rush follows on the heels of the Mexican–American War, bringing tens of thousands of immigrants to California and eliminating the United States' dependence on foreign gold.

Civil rights

Women's rights

- July 19, 1848 – Women's rights, 1848 – Seneca Falls Convention: The 2-day Women's Rights Convention opens in Seneca Falls, New York, and the "Bloomers" are introduced at the feminist convention.

Popular culture

Literature

- Charles Dickens publishes The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, A Christmas Carol, Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son and David Copperfield.

- Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls (Russian: Мёртвые души, Myortvyje dushi) is published in 1842.

- Søren Kierkegaard publishes his philosophical book Enten ‒ Eller (Either/Or) in 1843.

- Alexandre Dumas publishes Les Trois Mousquetaires (The Three Musketeers) in 1844 and Le Comte de Monte-Cristo (The Count of Monte Cristo) in 1844/45.

- Edgar Allan Poe releases The Raven in 1845, earning $10 for the piece.

- Charlotte Brontë's second novel, Jane Eyre, is published in 1847.

- Emily Brontë publishes Wuthering Heights, also in 1847.

- William Makepeace Thackeray publishes Vanity Fair in 1848.

- July 17, 1841 – First edition of the humorous magazine Punch published in London.[47]

- 1843 – Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Tell-Tale Heart is first published.

- January 29, 1845 – "The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe is published for the first time (New York Evening Mirror).

- 1845 – Elizabeth Barret Browning writes her Sonnets from the Portuguese (1845–1846).

- 1845 – Heinrich Hoffmann publishes a book (Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder) introducing his character Struwwelpeter, in Germany.

- October 16, 1847 – Charlotte Brontë publishes Jane Eyre under the pen name of Currer Bell.

- December 14, 1847 – Emily Brontë and Anne Brontë publish Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, respectively, in a 3-volume set under the pen names of Ellis Bell and Acton Bell.

- 1848 – Elizabeth Gaskell publishes Mary Barton anonymously.

Theatre

- February 6, 1843 – The Virginia Minstrels perform the first minstrel show, at the Bowery Amphitheatre in New York City.

Music

- February 11, 1840 – Gaetano Donizetti's opera La fille du régiment premieres in Paris.

- June 28, 1841 – Ballet Giselle first presented by the Ballet du Théâtre de l'Académie Royale de Musique at the Salle Le Peletier in Paris, France.

- March 9, 1842 – Giuseppe Verdi's third opera Nabucco premieres in Milan; its success establishes Verdi as one of Italy's foremost opera writers.

- February 11, 1843 – Giuseppe Verdi's opera I Lombardi alla prima crociata premieres at La Scala in Milan.

- November 3, 1844 – Giuseppe Verdi's I due Foscari debuts at Teatro Argentina, Rome.

- March 13, 1845 – The Violin Concerto by Felix Mendelssohn premieres in Leipzig, with Ferdinand David as soloist.

- July 7, 1845 – Jules Perrot presents the ballet divertissement Pas de Quatre to an enthusiastic London audience.

- June 28, 1846 – The Saxophone is patented by Adolphe Sax.[48]

- March 14, 1847 – Verdi's opera Macbeth premieres at Teatro della Pergola in Florence, Italy.

- 1848 – The Shaker song Simple Gifts is written by Joseph Brackett in Alfred, Maine.

- 1848 – Richard Wagner begins writing the libretto that will become Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

Sports

- March 2, 1842 – Gaylad, ridden by Tom Olliver, wins the Grand National at Aintree Racecourse.

- September 25–September 27, 1844 – The first ever international cricket match is played in New York City, United States v Canadian Provinces.

- Baseball - During the 1840s, "town ball" evolved into the modern game of baseball, with the development of the "New York game" in the 1840s. The New York Knickerbockers were founded in 1845, and played the first known competitive game between two organized clubs in 1846. The "New York Nine" defeated the Knickerbockers at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, by a score of 23 to 1.

Fashion

Fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by a narrow, natural shoulder line following the exaggerated puffed sleeves of the later 1820s fashion and 1830s fashion. The narrower shoulder was accompanied by a lower waistline for both men and women.

Art

- 1840 – J. M. W. Turner first displays his painting The Slave Ship.

Religion and Philosophy

- The American Transcendentalism movement is in full form mostly during this decade.

- February 1840 – The Rhodes blood libel is made against the Jews of Rhodes.

- February 5, 1840 – The murder of a Capuchin friar and his Greek servant leads to the Damascus affair, a highly publicized case of blood libel against the Jews of Damascus.

- June 6, 1841 Marian Hughes becomes the first woman to take religious vows in communion with the Anglican Province of Canterbury since the Reformation, making them privately to E. B. Pusey in Oxford.[49]

- July – Scottish missionary David Livingstone arrives at Kuruman in the Northern Cape, his first posting in Africa.

- May 18, 1843 – The Disruption in Edinburgh of the Free Church of Scotland from the Church of Scotland.

- October 16, 1843 – Søren Kierkegaard's philosophical book Fear and Trembling is first published.

- March 21, 1844 – The Bahá'í calendar begins.

- March 23, 1844 – Edict of Toleration, allowing Jews to settle in the Holy Land.

- May 23, 1844 – Persian Prophet The Báb privately announces his revelation to Mullá Husayn, just after sunset, founding the Bábí faith (later evolving into the Bahá'í Faith as the Báb intended) in Shiraz, Persia (now Iran). Contemporaneously, on this day in nearby Tehran, was the birth of `Abdu'l-Bahá; the eldest Son of Bahá'u'lláh, Prophet-Founder of the Bahá'í Faith, the inception of which, the Báb's proclaimed His own mission was to herald. `Abdu'l-Bahá Himself was later proclaimed by Bahá'u'lláh to be His own successor, thus being the third "central figure" of the Bahá'í Faith.

- June 27, 1844 – Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, and his brother Hyrum, are killed in Carthage Jail, Carthage, Illinois, by an armed mob, leading to a Succession crisis. John Taylor, future president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is severely injured but survives.

- August 8, 1844 – During a meeting held in Nauvoo, Illinois, the Quorum of the Twelve, headed by Brigham Young, is chosen as the leading body of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- October 22, 1844 – This second date, predicted by the Millerites for the Second Coming of Jesus, leads to the Great Disappointment. The Seventh-day Adventist Church denomination of the Christian religion believe this date to be the starting point of the Investigative judgment just prior to the Second Coming of Jesus as declared in the 26th of 28 fundamental doctrines of Seventh-day Adventists.[50]

- October 23, 1844 – The Báb publicly proclaimed to be the promised one of Islam (the Qá'im, or Mahdi). He is also considered to be simultaneously the return of Elijah, John the Baptist, and the "Ushídar-Máh" referred to in the Zoroastrian scriptures.[51] He announces to the world the coming of "He whom God shall make manifest". He is considered the forerunner of Bahá'u'lláh, 1844 – the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, 1844 – whose claims include being the return of Jesus.

- October 9, 1845 – The eminent and controversial Anglican, John Henry Newman, is received into the Roman Catholic Church.

- February 10, 1846 – Many Mormons begin their migration west from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Great Salt Lake, led by Brigham Young.

- June 16, 1846 – Pope Pius IX succeeds Pope Gregory XVI as the 255th pope. He will reign for 31½ years (the longest definitely confirmed).

- September 19, 1846 – The Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to two children in La Salette, France.

- 1848 – John Bird Sumner becomes archbishop of Canterbury.

- March 28, 1849 – Four Christians are ordered burnt alive in Antananarivo, Madagascar by Queen Ranavalona I and 14 others are executed.

Disasters, natural events, and notable mishaps

- January 13, 1840 – The steamship Lexington burns and sinks in icy waters, four miles off the coast of Long Island; 139 die, only four survive.

- May 7, 1840 – The Great Natchez Tornado: A massive tornado strikes Natchez, Mississippi, during the early afternoon hours. Before it is over, 317 people are killed and 109 injured. It is the second deadliest tornado in U.S. history.

- January 30, 1841 – A fire ruins and destroys two-thirds of the villa (modern-day city) of Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.

- February 20, 1841 – The Governor Fenner, carrying emigrants to the United States, sinks off Holyhead (Wales) with the loss of 123 lives.

- March 12, 1841 – SS President under the command of the legendary captain Richard Roberts founders in rough seas with all passengers and crew lost.

- October 30, 1841 – A fire at the Tower of London destroys its Grand Armoury and causes a quarter of a million pounds worth of damage.[52]

- October 29, 1842 – The Iberian Peninsula is struck by a category 2 hurricane.

- 1842 – Dzogchen Monastery is almost completely destroyed by an earthquake.

.jpg)

- February 28, 1844 – A gun on the USS Princeton explodes while the boat is on a Potomac River cruise, killing 2 United States Cabinet members and several others.

- June–July – The Great Flood of 1844 hits the Missouri River and Mississippi River.

- February 7, 1845 – In the British Museum, a drunken visitor smashes the Portland Vase, which takes months to repair.

- April 10, 1845 – A great fire destroys much of the American city of Pittsburgh.

- May 2, 1845 – A suspension bridge collapses in Great Yarmouth, England, leaving around 80 dead, mostly children.[53]

- May 19, 1845 – HMS Erebus and HMS Terror with 134 men, comprising Sir John Franklin's expedition to find the Northwest Passage, sail from Greenhithe on the Thames. They will last be seen in August entering Baffin Bay.[54]

- April 25, 1847 – The brig Exmouth carrying Irish emigrants from Derry bound for Quebec is wrecked off Islay with only three survivors from more than 250 on board.[55][56]

- August 24, 1848 – The U.S. barque Ocean Monarch is burnt out off the Great Orme, North Wales, with the loss of 178, chiefly emigrants.

- May 3, 1849 – The Mississippi River levee at Sauvé's Crevasse breaks, flooding much of New Orleans, Louisiana.

- May 10, 1849 – The Astor Place Riot takes place in Manhattan over a dispute between two Shakespearean actors. Over 20 people are killed.

- May 17, 1849 – The St. Louis Fire starts when a steamboat catches fire and nearly burns down the entire city.

- 1849 – Seven of the "best known" opium clippers go missing: Sylph, Coquette, Kelpie, Greyhound, Don Juan, Mischief, and Anna Eliza.[57]

Cholera

The second cholera pandemic (1829–1849), also known as the Asiatic Cholera Pandemic, was a Cholera pandemic that reached from India across western Asia to Europe, Great Britain and the Americas, as well as east to China and Japan.[58] Cholera caused more deaths, more quickly, than any other epidemic disease in the 19th century. It is exclusively a human disease, and it can spread through many means of travel, such as by persons via caravan, ship, and aeroplanes. Cholera is known most popularly to spread through warm fecal-contaminated river waters and contaminated foods. The causative microorganisms (Cholera vibrio) flourish by reaching humans. It is treatable with oral re-hydration therapy and preventable with adequate sanitation and water treatment.

Over 15,000 people died of cholera in Mecca in 1846.[10] A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848, and claimed 52,000 lives.[11]

In 1849, a second major outbreak occurred in Paris. In London, it was the worst outbreak in the city's history, claiming 14,137 lives, over twice as many as the 1832 outbreak. Cholera hit Ireland in 1849 and killed many of the Irish Famine survivors, already weakened by starvation and fever.[12] In 1849, cholera claimed 5,308 lives in the major port city of Liverpool, England, an embarkation point for immigrants to North America, and 1,834 in Hull, England.[6]

An outbreak in North America took the life of former U.S. President James K. Polk. Cholera, believed spread from Irish immigrant ship(s) from England, spread throughout the Mississippi river system, killing over 4,500 in St. Louis[6] and over 3,000 in New Orleans.[6] Thousands died in New York City, a major destination for Irish immigrants.[6]Cholera claimed 200,000 victims in Mexico.[13]

That year, cholera was transmitted along the California, Mormon and Oregon Trails as 6,000 to 12,000[14] are believed to have died on their way to the California Gold Rush, Utah and Oregon in the cholera years of 1849–1855.[6] It is believed more than 150,000 Americans died during the two pandemics between 1832 and 1849.[15][16]

During this pandemic, the scientific community varied in its beliefs about the causes of cholera. In France doctors believed cholera was associated with the poverty of certain communities or poor environment. Russians believed the disease was contagious, although doctors did not understand how it spread. The United States believed that cholera was brought by recent immigrants, specifically the Irish, and epidemiologists understand they were carrying disease from British ports. Lastly, some British thought the disease might rise from divine intervention.[17]

Establishments

Publications

- September 1843 –The Economist newspaper is first published in London.

- 1843 – The Friend, a Quaker weekly, is first published in London.

- August 28, 1845 – The journal Scientific American begins publication.

Institutions

Asia

- July 18, 1841 – The sixth bishop of Calcutta, Daniel Wilson, and Dr. James Taylor, Civil Surgeon at Dhaka, establish the first modern educational institution in the Indian subcontinent, Dhaka College.

Australia

- October 1, 1846 – Christ College, Tasmania, opens with the hope that it would develop along the lines of an Oxbridge college and provide the basis for university education in Tasmania. By the 21st century it will be the oldest tertiary institution in Australia.

Europe

- April 15, 1840 – King's College Hospital opens in London.

- August 15, 1843 – Tivoli Gardens, one of the oldest still intact amusement parks in the world, opens in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- June 6, 1844 – George Williams founds the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) in London.

- December 21, 1844 – The Rochdale Pioneers commence business at their cooperative in Rochdale, England.

- April 5, 1847 – The world's first municipally-funded civic public park, Birkenhead Park in Birkenhead on Merseyside in England, is opened.[59]

- October 12, 1847 – German inventor and industrialist Werner von Siemens founds Siemens AG & Halske.

- February 2, 1848 – John Henry Newman founds the first Oratory in the English-speaking world when he establishes the Birmingham Oratory at 'Maryvale', Old Oscott, England.

Africa

- 1845 – Eugénie Luce founds the Luce Ben Aben School in Algiers.[60]

North America

- 1843 – Saint Louis University School of Law becomes the first law school west of the Mississippi River.

- January 15, 1844 – The University of Notre Dame receives its charter from Indiana.

- February 1, 1845 – Anson Jones, President of the Republic of Texas, signs the charter officially creating Baylor University. Baylor is the oldest university in the State of Texas operating under its original name.

- October 10, 1845 – In Annapolis, Maryland, the Naval School (later renamed the United States Naval Academy) opens with fifty midshipmen and seven professors.

- November 1, 1848 – In Boston, Massachusetts, the first medical school for women, The Boston Female Medical School (which later merges with Boston University School of Medicine), opens.

- November 1849 – Austin College receives a charter in Huntsville, Texas.

Other

- February 4, 1841 – First known reference to Groundhog Day, in the diary of a James Morris.

People

World leaders

- Daoguang Emperor (Qing dynasty)

- Emperor Ferdinand I (Austria)

- Chancellor Klemens Wenzel von Metternich (Austria)

- Emperor Franz Josef (Austria-Hungary)

- King Louis-Philippe (July Monarchy France)

- King Frederick William IV of Prussia (Prussia)

- King Leopold I of Belgium (Belgium)

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius IX

- Emperor Nicholas I (Russia)

- Bahadur Shah Zafar (Mughal Empire)

- Queen Isabella II (Spain)

- King Charles XIV John (Sweden)

- King Oscar I (Sweden)

- Queen Victoria (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- Prime Minister Lord Melbourne (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- Prime Minister Lord John Russell (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- President Martin Van Buren (United States)

- President William Henry Harrison (United States)

- President John Tyler (United States)

- President James K. Polk (United States)

- President Zachary Taylor (United States)

- President Sam Houston (Republic of Texas)

- President Anson Jones (Republic of Texas)

- Sultan Abd-ul-Mejid I (Ottoman Empire)

- Shahs of Persia (Qajar dynasty)

- Mohammad Shah Qajar, (b. 1810 – d. 1848) Shah from 1834 to 1848

- Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, 1848–1896

Deaths

- Mohammad Shah Qajar, (b. 1810 – d. 1848) Shah from 1834 to 1848

References

- Robert Sobel Conquest And Conscience: The 1840s (1971)

- ↑ "When Will the Great Game End?". orientalreview.org. 15 November 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ Gandamak at britishbattles.com

- ↑ Dattar, C. L. "ZORĀWAR SIṄGH (1786-1841)". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala.

- 1 2 Penguin Pocket On This Day. Penguin Reference Library. 2006. ISBN 0-14-102715-0.

- ↑ R.J.W. Evans and Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, eds., The Revolutions in Europe 1848–1849 (2000) pp v, 4

- ↑ Serbia's Role in the Conflict in Vojvodina 1848-49, Ohio State University, http://www.ohio.edu/chastain/rz/serbvio.htm

- ↑ Nor did it reach Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Portugal, or the Ottoman Empire. Evans and Strandmann (2000) p 2

- ↑ Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 23.

- ↑ "WHKMLA : History of Sweden".

- ↑ Palmer, Alan; Palmer, Veronica (1992). The Chronology of British History. London: Century Ltd. pp. 269–270. ISBN 0-7126-5616-2.

- ↑ "The Irish Potato Famine". Digital History. 7 November 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ↑ Woodham-Smith, Cecil (1991), The Great Hunger, p. 19

- ↑ Kinealy, Christine (1994), This Great Calamity, Gill & Macmillan, pp. xvi–ii, 2–3, ISBN 0-7171-4011-3

- ↑ O'Neill, Joseph R. (2009), The Irish Potato Famine, ABDO, p. 1, ISBN 978-1-60453-514-3

- ↑ Ó Gráda, Cormac (2006), Ireland's Great Famine: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Dublin Press, p. 7, ISBN 978-1-904558-57-6

- ↑ Killen, Richard (2003), A Short History of Modern Ireland, Gill and Macmillan Ltd

- ↑ Vaughan, W.E; Fitzpatrick, A.J (1978), W. E. Vaughan; A. J. Fitzpatrick, eds., Irish Historical Statistics, Population, 1821/1971, Royal Irish Academy

- ↑ Donnelly, James S., Jr. (1995), Poirteir, Cathal, ed., Mass Eviction and the Irish Famine: The Clearances Revisited", from The Great Irish Famine, Dublin, Ireland: Mercier Press

- ↑ Giraud, Victor (1890). Les lacs de l'Afrique Équatoriale : voyage d'exploration exécuté de 1883 à 1885 (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie. p. 31.

- ↑ Palmer, Alan; Palmer, Veronica (1992). The Chronology of British History. London: Century Ltd. pp. 266–267. ISBN 0-7126-5616-2.

- ↑ Buckner, Philip, ed. (2008). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 37–40, 56–59, 114, 124–125. ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1.

- ↑ Romney, Paul (Spring 1989). "From Constitutionalism to Legalism: Trial by Jury, Responsible Government, and the Rule of Law in the Canadian Political Culture". Law and History Review. University of Illinois Press. 7 (1): 128. doi:10.2307/743779.

- ↑ Evenden, Leonard J; Turbeville, Daniel E (1992). "The Pacific Coast Borderland and Frontier". In Janelle, Donald G. Geographical snapshots of North America. Guilford Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-89862-030-6.

- ↑ Dallas Historical Society (2002-12-30). "Dallas History". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ↑ Rives. The United States and Mexico, vol. 2. p. 658.

- ↑ When the British decided they were going to bring Indians to Trinidad this year, most of the traditional British ship owners did not wish to be involved. The ship was originally named Cecrops, but upon delivery was renamed to Fath Al Razack. The ship left Calcutta on February 16.

- ↑ Fuegi, John; Francis, Jo (October–December 2003). "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 25 (4): 16–26. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887.

- ↑ "Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace". Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ↑ Menabrea, L. F. (1843). "Sketch of the Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage". Scientific Memoirs. 3. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ↑ von Mayer, J. R. (1842). "Bemerkungen über die Kräfte der unbelebten Nature ("Remarks on the forces of inorganic nature")". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 43: 233–40. doi:10.1002/jlac.18420420212. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "William Rowan Hamilton Plaque". Geograph. 2007. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ Joule, J. P. (1843). "On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat". Abstracts of the Papers Communicated to the Royal Society of London. 5: 839. doi:10.1098/rspl.1843.0196. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ↑ Owen, R. (1842). "Report on British Fossil Reptiles." Part II. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Plymouth, England.

- ↑ First communicated to the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh, November 10, and published in a pamphlet, Notice of a New Anæsthetic Agent, in Edinburgh, November 12.

- ↑ Gordon, H. Laing (2002). Sir James Young Simpson and Chloroform (1811–1870). Minerva Group, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4102-0291-8. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ↑ "Antarctic Exploration — Chronology". Quark Expeditions. 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- ↑ Guillon, Jacques (1986). Dumont d'Urville. Paris: France-Empire. ISBN 2-7048-0472-9.

- ↑ Ross, Voyage to the Southern Seas, 1, pp. 216–8.

- ↑ Coleman, E. C. (2006). The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration, from Frobisher to Ross. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 335. ISBN 0-7524-3660-0.

- ↑ Palmer, Alan; Palmer, Veronica (1992). The Chronology of British History. London: Century Ltd. pp. 263–264. ISBN 0-7126-5616-2.

- ↑ "Royal Visit". The Bristol Mirror. 20 July 1843. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Meggs, Philip B. (1998). A History of Graphic Design (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-471-29198-5. It receives U.S. Patent 5,199 in 1847 and is placed in commercial use the same year.

- ↑ Fox, Stephen (2003). Transatlantic: Samuel Cunard, Isambard Brunel, and the Great Atlantic Steamships. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019595-3.

- ↑ "Great Britain". The Ships List. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 4,750

- ↑ Buday, György (1992). "The history of the Christmas card". Omnigraphics: 8.

- ↑ Spielmann, Marion Harry (1895). The History of "Punch". p. 27.

- ↑ Hart, Hugh (2010-06-28). "June 28, 1846: Parisian Inventor Patents Saxophone". Wired. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ↑ Bonham, Valerie (2004). "Hughes, Marian Rebecca (1817–1912)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2010-11-26. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ "Beliefs". Seventh-day Adventist Church.

- ↑ Shoghi, Effendi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 58. ISBN 0-87743-020-9. Archived from the original on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ↑ Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher (1995). The London Encyclopaedia. Macmillan. p. 287. ISBN 0-333-57688-8.

- ↑ "The Great Yarmouth Suspension Bridge Disaster – May 2nd 1845" (PDF). Broadland Memories. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ The Hutchinson Factfinder. Helicon. 1999. p. 549. ISBN 1-85986-000-1.

- ↑ "The Exmouth - a terrible tragedy on Islay". Isle of Islay. 2011. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ↑ "The Exmouth shipwreck off the Antrim Coast, Northern Ireland". My Secret Northern Ireland. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ↑ Lubbock, Basil (1933). The Opium Clippers. Boston, MA: Charles E. Lauriat Co. p. 310.

- ↑ "Cholera's seven pandemics". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. December 2, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-11.Note: The second pandemic started in India and reached Russia by 1830, then spreading into Finland and Poland. A two-year outbreak began in England in October 1831 and claimed 22,000 lives. Irish immigrants fleeing poverty and the Great Potato Famine, carried the disease from Europe to North America. Soon after the immigrants' arrival in Canada in the summer of 1832, 1,220 people died in Montreal and another 1,000 across Quebec. The disease entered the U.S. via ship traffic through Detroit and New York City. Spread by ship passengers, it reached Latin America by 1833. Another outbreak across England and Wales began in 1848, killing 52,000 over two years.

- ↑ "The History of Birkenhead Park". Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ↑ "Luce Ben Aben School of Arab Embroidery I, Algiers, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

Further reading

- Joseph Irving (1880). Annals of Our Time...1837 to...1871. London: Macmillan and Co.