Early modern Britain

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the British Isles |

|

| Prehistoric period |

| Classical period |

| Medieval period |

| Early modern period |

| Late modern period |

| By region |

|

|

Early modern Britain is the history of the island of Great Britain roughly corresponding to the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Major historical events in Early Modern British history include numerous wars, especially with France, along with the English Renaissance, the English Reformation and Scottish Reformation, the English Civil War, the Restoration of Charles II, the Glorious Revolution, the Treaty of Union, the Scottish Enlightenment and the formation and collapse of the First British Empire.

England during the Tudor period (1486–1603)

English Renaissance

The term, "English Renaissance" is used by many historians to refer to a cultural movement in England in the 16th and 17th centuries that was heavily influenced by the Italian Renaissance. This movement is characterised by the flowering of English music (particularly the English adoption and development of the madrigal), notable achievements in drama (by William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson), and the development of English epic poetry (most famously Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene).[1]

The idea of the Renaissance has come under increased criticism by many cultural historians, and some have contended that the "English Renaissance" has no real tie with the artistic achievements and aims of the northern Italian artists (Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello) who are closely identified with the Renaissance.

Other cultural historians have countered that, regardless of whether the name "renaissance" is apt, there was undeniably an artistic flowering in England under the Tudor monarchs, culminating in Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

The rise of the Tudors

Some scholars date the beginning of Early Modern Britain to the end of the Wars of the Roses and the crowning of Henry Tudor in 1485 after his victory at the battle of Bosworth Field. Henry VII's largely peaceful reign ended decades of civil war and brought the peace and stability to England that art and commerce need to thrive. A major war on English soil would not occur again until the English Civil War of the 17th century.[2][3][4]

During this period Henry VII and his son Henry VIII greatly increased the power of the English monarchy. A similar pattern was unfolding on the continent as new technologies, such as gunpowder, and social and ideological changes undermined the power of the feudal nobility and enhanced that of the sovereign. Henry VIII also made use of the Protestant Reformation to seize the power of the Roman Catholic Church, confiscating the property of the monasteries and declaring himself the head of the new Anglican Church. Under the Tudors the English state was centralized and rationalized as a bureaucracy built up and the government became run and managed by educated functionaries. The most notable new institution was the Star Chamber.

The new power of the monarch was given a basis by the notion of the divine right of kings to rule over their subjects. James I was a major proponent of this idea and wrote extensively on it.

The same forces that had reduced the power of the traditional aristocracy also served to increase the power of the commercial classes. The rise of trade and the central importance of money to the operation of the government gave this new class great power, but power that was not reflected in the government structure. This would lead to a long contest during the 17th century between the forces of the monarch and parliament.

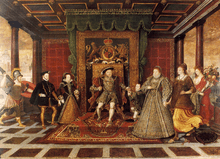

Elizabethan era (1558–1603)

The Elizabethan Era is the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) and is known to be a golden age in English history. It was the height of the English Renaissance and saw the flowering of English literature and poetry. This was also the time during which Elizabethan theatre was famous and William Shakespeare, among others, composed plays that broke away from England's past style of plays and theatre. It was an age of expansion and exploration abroad, while at home the Protestant Reformation became entrenched in the national mindset.[5][6]

The Elizabethan Age is viewed so highly because of the contrasts with the periods before and after. It was a brief period of largely internal peace between the English Reformation and the battles between Protestants and Catholics and the battles between parliament and the monarchy that engulfed the 17th century. The Protestant/Catholic divide was settled, for a time, by the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, and parliament was not yet strong enough to challenge royal absolutism. England was also well-off compared to the other nations of Europe. The Italian Renaissance had come to an end under the weight of foreign domination of the peninsula. France was embroiled in its own religious battles that would only be settled in 1598 with the Edict of Nantes. In part because of this, but also because the English had been expelled from their last outposts on the continent, the centuries long conflict between France and England was largely suspended for most of Elizabeth's reign.

The one great rival was Spain, with which England conflicted both in Europe and the Americas in skirmishes that exploded into the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. An attempt by Philip II of Spain to invade England with the Spanish Armada in 1588 was famously defeated, but the tide of war turned against England with a disastrously unsuccessful attack upon Spain, the Drake-Norris Expedition of 1589. Thereafter Spain provided some support for Irish Catholics in a draining guerilla war against England, and Spanish naval and land forces inflicted a series of defeats upon English forces. This badly damaged both the English Exchequer and economy that had been so carefully restored under Elizabeth's prudent guidance. English colonisation and trade would be frustrated until the signing of the Treaty of London the year following Elizabeth's death.

England during this period had a centralised, well-organised, and effective government, largely a result of the reforms of Henry VII and Henry VIII. Economically, the country began to benefit greatly from the new era of trans-Atlantic trade.

Scotland from 15th century to 1603

Scotland advanced markedly in educational terms during the 15th century with the founding of the University of St Andrews in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1450 and the University of Aberdeen in 1495, and with the passing of the Education Act 1496.[7][8]

In 1468 the last great acquisition of Scottish territory occurred when James III married Margaret of Denmark, receiving the Orkney Islands and the Shetland Islands in payment of her dowry.

After the death of James III in 1488, during or after the Battle of Sauchieburn, his successor James IV successfully ended the quasi-independent rule of the Lord of the Isles, bringing the Western Isles under effective Royal control for the first time. In 1503, he married Henry VII's daughter, Margaret Tudor, thus laying the foundation for the 17th century Union of the Crowns. James IV's reign is often considered to be a period of cultural flourishing, and it was around this period that the European Renaissance began to infiltrate Scotland. James IV was the last known Scottish king known to speak Gaelic, although some suggest his son could also.

In 1512, under a treaty extending the Auld Alliance, all nationals of Scotland and France also became nationals of each other's countries, a status not repealed in France until 1903 and which may never have been repealed in Scotland. However a year later, the Auld Alliance had more disastrous effects when James IV was required to launch an invasion of England to support the French when they were attacked by the English under Henry VIII. The invasion was stopped decisively at the battle of Flodden Field during which the King, many of his nobles, and over 10,000 troops—The Flowers of the Forest—were killed. The extent of the disaster impacted throughout Scotland because of the large numbers killed, and once again Scotland's government lay in the hands of regents. The song The Flooers o' the Forest commemorated this, an echo of the poem Y Gododdin on a similar tragedy in about 600.

When James V finally managed to escape from the custody of the regents with the aid of his redoubtable mother in 1528, he once again set about subduing the rebellious Highlands, Western and Northern isles, as his father had had to do. He married the French noblewoman Marie de Guise. His reign was fairly successful, until another disastrous campaign against England led to defeat at the battle of Solway Moss (1542). James died a short time later. The day before his death, he was brought news of the birth of an heir: a daughter, who became Mary, Queen of Scots. James is supposed to have remarked in Scots that "it cam wi a lass, it will gang wi a lass"—referring to the House of Stewart which began with Walter Stewart's marriage to the daughter of Robert the Bruce. Once again, Scotland was in the hands of a regent, James Hamilton, Earl of Arran.

Mary, Queen of Scots

Within two years, the Rough Wooing, Henry VIII's military attempt to force a marriage between Mary and his son, Edward, had begun. This took the form of border skirmishing. To avoid the "rough wooing", Mary was sent to France at the age of five, as the intended bride of the heir to the French throne. Her mother stayed in Scotland to look after the interests of Mary—and of France—although the Earl of Arran acted officially as regent.

In 1547, after the death of Henry VIII, forces under the English regent Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset were victorious at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh, the climax of the Rough Wooing and followed up by occupying Edinburgh. However it was to no avail since much of Scotland was still an unstable environment. She did not do well and after only seven turbulent years, at the end of which Protestants had gained complete control of Scotland, she had perforce to abdicate. Imprisoned for a time in Loch Leven Castle, she eventually escaped and attempted to regain the throne by force. After her defeat at the Battle of Langside in 1568 she took refuge in England, leaving her young son, James VI, in the hands of regents. In England she became a focal point for Catholic conspirators and was eventually executed on the orders of her kinswoman Elizabeth I.

Protestant Reformation

During the 16th century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation. In the earlier part of the century, the teachings of first Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to influence Scotland. the execution of a number of Protestant preachers, most notably the Lutheran influenced Patrick Hamilton in 1528 and later the proto-Calvinist George Wishart in 1546 who was burnt at the stake in St. Andrews by Cardinal Beaton for heresy, did nothing to stem the growth of these ideas. Beaton was assassinated shortly after the execution of George Wishart.

The eventual Reformation of the Scottish Church followed a brief civil war in 1559–60, in which English intervention on the Protestant side was decisive. A Reformed confession of faith was adopted by Parliament in 1560, while the young Mary, Queen of Scots, was still in France. The most influential figure was John Knox, who had been a disciple of both John Calvin and George Wishart. Roman Catholicism was not totally eliminated, and remained strong particularly in parts of the highlands.

The Reformation remained somewhat precarious through the reign of Queen Mary, who remained Roman Catholic but tolerated Protestantism. Following her deposition in 1567, her infant son James VI was raised as a Protestant. In 1603, following the death of the childless Queen Elizabeth I, the crown of England passed to James. He took the title James I of England and James VI of Scotland, thus unifying these two countries under his personal rule. For a time, this remained the only political connection between two independent nations, but it foreshadowed the eventual 1707 union of Scotland and England under the banner of the Great Britain.

17th century

Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns refers to the accession of James VI, King of Scots, to the throne of England as James I, in March 1603, thus uniting Scotland and England under one monarch. This followed the death of his unmarried and childless cousin, Queen Elizabeth I of England, the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty. The term itself, though now generally accepted, is misleading; for properly speaking this was merely a personal or dynastic union, the Crowns remaining both distinct and separate until the Acts of Union in 1707 during the reign of the last monarch of the Stuart Dynasty, Queen Anne.

This event was the result of an event in August 1503: James IV, King of Scots, married Margaret Tudor, the eldest daughter of Henry VII of England as a consequence of the Treaty of Perpetual Peace, concluded the previous year which, in theory, ended centuries of English-Scottish rivalry. This marriage merged the Stuarts with England's Tudor line of succession. Almost 100 years later, in the last decade of the reign of Elizabeth I of England, it was clear to all that James of Scots, the great-grandson of James IV and Margaret Tudor, was the most acceptable heir.

From 1601, in the last years of Elizabeth I's life, certain English politicians, notably her chief minister Sir Robert Cecil,[9] maintained a secret correspondence with James in order to prepare in advance for a smooth succession. Cecil advised James not to press the matter of the succession upon the queen but simply to treat her with kindness and respect.[10] The approach proved effective: "I trust that you will not doubt," Elizabeth wrote to James, "but that your last letters are so acceptably taken as my thanks cannot be lacking for the same, but yield them you in grateful sort."[11] In March 1603, with the queen clearly dying, Cecil sent James a draft proclamation of his accession to the English throne. Strategic fortresses were put on alert, and London placed under guard. Elizabeth died in the early hours of 24 March. Within eight hours, James was proclaimed king in London, the news received without protest or disturbance.[12]

The Jacobean era refers to a period in English and Scottish history that coincides with the reign of James I (1603–1625). The Jacobean era succeeds the Elizabethan era and precedes the Caroline era, and specifically denotes a style of architecture, visual arts, decorative arts, and literature that is predominant of that period.

The Caroline era refers to a period in English and Scottish history that coincides with the reign of Charles I (1625—1642). The Caroline era succeeds the Jacobean era, the reign of Charles's father James I (1603–1625); it was succeeded by the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the English Interregnum (1651–1660).

English Civil War

The English Civil War consisted of a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians (known as Roundheads) and Royalists (known as Cavaliers) between 1642 and 1651. The first (1642–1646) and second (1648–1649) civil wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third war (1649–1651) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The Civil War ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651. The Diggers were a group begun by Gerrard Winstanley in 1649 who attempted to reform the existing social order with an agrarian lifestyle based upon their ideas for the creation of small egalitarian rural communities. They were one of a number of nonconformist dissenting groups that emerged around this time.

The English Interregnum was the period of parliamentary and military rule in the land occupied by modern-day England and Wales after the English Civil War. It began with the regicide of Charles I in 1649 and ended with the restoration of Charles II in 1660.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son Charles II, and the replacement of the English monarchy with first the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and then with a Protectorate (1653–1659), under the personal rule of Oliver Cromwell, followed by the Protectorate under Richard Cromwell from 1658 to 1659 and the second period of the Commonwealth of England from 1659 until 1660. The monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship in England came to an end, and the victors consolidated the already-established Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. Constitutionally, the wars established a precedent that British monarchs could not govern without the consent of Parliament, although this concept became firmly established only with the deposition of James II of England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the passage of the English Bill of Rights, and the Hanoverian succession. For the remainder of the century, Britain was ruled by William III of England, until 1694 jointly with his wife and first cousin, the daughter of James II, Mary II of England.

Anglo Dutch Wars

The Anglo-Dutch Wars were a series of three wars which took place between the English and the Dutch from 1652 to 1674. The causes included political disputes and increasing competition from merchant shipping.[13] Religion was not a factor, since both sides were Protestant. The British in the first war (1652-54) had the naval advantage with larger numbers of more powerful "ships of the line" which were well suited to the naval tactics of the era.. The British also captured numerous Dutch merchant ships. In the second war (1665-67) Dutch naval victories followed. This second war cost London ten times more than it had planned on, and the king sued for peace in 1667 with the Treaty of Breda. It ended the fights over "mercantilism" (that is, the use of force to protect and expand national trade, industry, and shipping.) Meanwhile, the French were building up fleets that threatened both the Netherlands and Great Britain. In third war (1672-74), The British counted on a new alliance with France but the outnumbered Dutch outsailed both of them, and King Charles II ran short of money and political support. The Dutch gained domination of sea trading routes until 1713. The British gained the thriving colony of New Netherland, and renamed it New York.[14]

18th century

The 18th century was characterized by numerous major wars,[15] especially with France, with the growth and collapse of the First British Empire, with the origins of the Second British Empire, and with steady economic and social growth at home.[16][17]

Peace between England and the Netherlands in 1688 meant that the two countries entered the Nine Years' War as allies, but the conflict – waged in Europe and overseas between France, Spain and the Anglo-Dutch alliance – left the English a stronger colonial power than the Dutch, who were forced to devote a larger proportion of their military budget on the costly land war in Europe.[18] The 18th century would see England (after 1707, Great Britain) rise to be the world's dominant colonial power, and France becoming its main rival on the imperial stage.[19]

In 1701, England, Portugal and the Netherlands sided with the Holy Roman Empire against Spain and France in the War of the Spanish Succession. The conflict, which France and Spain were to lose, lasted until 1714. The British Empire was territorially enlarged: from France, gaining Newfoundland and Acadia, and from Spain, Gibraltar and Minorca. Gibraltar, which is still a British overseas territory to this day, became a critical naval base and allowed Britain to control the Atlantic entry and exit point to the Mediterranean.[20]

Treaty of Union

The united Kingdom of Great Britain was born on May 1, 1707, shortly after the parliaments of Scotland and England had ratified the Treaty of Union of 1706 by each approving Acts of Union combining the two parliaments and the two royal titles. Deeper political integration had been a key policy of Queen Anne (reigned 1702–14). Under the aegis of the Queen and her advisors a Treaty of Union was drawn up, and negotiations between England and Scotland began in earnest in 1706.[21]

Scottish proponents of union believed that failure to accede to the Bill would result in the imposition of union under less favourable terms, and months of fierce debate in both capital cities and throughout both kingdoms followed. In Scotland, the debate on occasion dissolved into civil disorder, most notably by the notorious 'Edinburgh Mob'. The prospect of a union of the kingdoms was deeply unpopular among the Scottish population at large, and talk of an uprising was widespread.[22] However Scotland could not long continue. Following the financially disastrous Darien Scheme, the near-bankrupt Parliament of Scotland reluctantly accepted the proposals. Supposed financial payoffs to Scottish parliamentarians were later referred to by Robert Burns when he wrote "We're bought and sold for English gold, Such a Parcel of Rogues in a Nation![23] Recent historians, however, have emphasized the legitimacy of the vote.[24]

The Acts of Union took effect in 1707, uniting the separate Parliaments and crowns of England and Scotland and forming the single Kingdom of Great Britain. Queen Anne (already Queen of both England and Scotland) became formally the first occupant of the unified British throne, with Scotland sending forty-five Members to join all existing Members from the parliament of England in the new House of Commons of Great Britain, as well as 16 representative peers to join all existing peers from the parliament of England in the new House of Lords.

Jacobite risings

The Jacobites wanted to replace the Hanoverian kings with the son of James II. They attempted armed invasions to conquer Britain.[25] The major Jacobite Rebellions in 1715 and 1745 were speedily suppressed. Their defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 ending any realistic hope of a Stuart restoration. The great majority of Tories refused to support the Jacobites publicly, although there were numerous quiet supporters.[26]

South Sea Bubble

The era was prosperous as entrepreneurs extended the range of their business around the globe. By the 1720s Britain was one of the most prosperous countries in the world, and Daniel Defoe boasted:

- we are the most "diligent nation in the world. Vast trade, rich manufactures, mighty wealth, universal correspondence, and happy success have been constant companions of England, and given us the title of an industrious people."[27]

The South Sea Bubble was a business enterprise that exploded in scandal. The South Sea Company was a private business corporation set up in London ostensibly to grant trade monopolies in South America. Its actual purpose was to renegotiate previous high-interest government loans amounting to ₤31 million through market manipulation and speculation. It issued stock four times in 1720 that reached about 8,000 investors. Prices kept soaring every day, from ₤130 a share to ₤1,000, with insiders making huge paper profits. The Bubble collapsed overnight, ruining many speculators. Investigations showed bribes had reached into high places—even to the king. Robert Walpole managed to wind it down with minimal political and economic damage, although some losers fled to exile or committed suicide.[28][29]

Warfare and finance

From 1700 to 1850, Britain was involved in 137 wars or rebellions. Apart from losing the American War of Independence, it was generally successful in warfare, and was especially successful in financing its military commitments. France and Spain, by contrast, went bankrupt. Britain maintained a relatively large and expensive Royal Navy, along with a small standing army. When the need arose for soldiers it hired mercenaries or financed allies who fielded armies. The rising costs of warfare forced a shift in government financing from the income from royal agricultural estates and special imposts and taxes to reliance on customs and excise taxes and, after 1790, an income tax. Working with bankers in the City, the government raised large loans during wartime and paid them off in peacetime. The rise in taxes amounted to 20% of national income, but the private sector benefited from the increase in economic growth. The demand for war supplies stimulated the industrial sector, particularly naval supplies, munitions and textiles, which gave Britain an advantage in international trade during the postwar years.[30][31][32]

British Empire

The Seven Years' War, which began in 1756, was the first war waged on a global scale, fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and coastal Africa. The signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763) had important consequences for Britain and its empire. In North America, France's future as a colonial power there was effectively ended with the ceding of New France to Britain (leaving a sizeable French-speaking population under British control) and Louisiana to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain. In India, the Carnatic War had left France still in control of its enclaves but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British client states, effectively leaving the future of India to Britain. The British victory over France in the Seven Years War therefore left Britain as the world's dominant colonial power.[33]

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of resentment of the British Parliament's ability to tax American colonists without their consent.[34] Disagreement turned to violence and in 1775 the American War of Independence began. The following year, the colonists declared the independence of the United States and with economic and naval assistance from France, would go on to win the war in 1783.

The loss of the United States, at the time Britain's most populous colony, is seen by historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires,[35] in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that free trade should replace the old mercantilist policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal. The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783[36] confirmed Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.

During its 1st century of operation, the focus of the British East India Company had been trade, not the building of an empire in India. Company interests turned from trade to territory during the 18th century as the Mughal Empire declined in power and the British East India Company struggled with its French counterpart, La Compagnie française des Indes orientales, during the Carnatic Wars of the 1740s and 1750s. The Battle of Plassey, which saw the British, led by Robert Clive, defeat the French and their Indian allies, left the Company in control of Bengal and a major military and political power in India. In the following decades it gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or indirectly via local puppet rulers under the threat of force of the Indian Army, 80% of which was composed of native Indian sepoys.

In 1770, James Cook became the first European to visit the eastern coast of Australia whilst on a scientific voyage to the South Pacific. In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of Botany Bay for the establishment of a penal settlement, and in 1787 the first shipment of convicts set sail, arriving in 1788.

At the threshold to the 19th century, Britain was challenged again by France under Napoleon, in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations.[37] It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was threatened: Napoleon threatened invasion of Britain itself, and with it, a fate similar to the countries of continental Europe that his armies had overrun. The Napoleonic Wars were therefore ones that Britain invested large amounts of capital and resources to win. French ports were blockaded by the Royal Navy, which won a decisive victory over the French fleet at Trafalgar in 1805.

Growth of state power

Recently historians have undertaken a deeper exploration of the growth of state power. The especially look at the long 18th century, from about 1660 to 1837 from four fresh perspectives.[38] The first approach, developed by Oliver MacDonagh, presented an expansive and centralized administrative state while deemphasizing the influence of Benthamite utilitarianism.[39] The second approach, as developed by Edward Higgs, conceptualizes the state as an information-gathering entity, paying special attention to local registrars and the census. He brings in such topics as spies, surveillance of Catholics, the 1605 Gunpowder Plot led by Guy Fawkes to overthrow the government, and the Poor Laws, and demonstrates similarities to the surveillance society of the 21st century. [40] John Brewer introduced the third approach with his depiction of the unexpectedly powerful, centralized 'fiscal-military' state during the eighteenth century. [41] [42] finally there have been numerous recent studies that explore the state as an abstract entity capable of commanding the loyalties of those people over whom it rules.

See also

- British colonisation of the Americas

- British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

- Company rule in India

- Early Modern English

- Early Modern English literature

- Early modern period

- Evolution of the British Empire

- History of Scotland

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- Historiography of the British Empire

Notes

- ↑ Dennis Austin Britton, "Recent Studies in English Renaissance Literature." English Literary Renaissance 45#3 (2015): 459-478.

- ↑ John A. Wagner and Susan Walters Schmid, eds. Encyclopedia of Tudor England (3 vol. 2011).

- ↑ J. A. Guy, Tudor England (1990) a leading comprehensive survey excerpt and text search

- ↑ Wallace McCaffrey, "Recent Writings on Tutor History," in Richard Schlatter, ed., Recent Views on British History: Essays on Historical Writing since 1966 (Rutgers UP, 1984), pp 1–34

- ↑ John A. Wagner, Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World: Britain, Ireland, Europe, and America (1999) online edition

- ↑ Penry Williams, The Later Tudors: England, 1547-1603 (The New Oxford History of England) (1998) excerpt and text search.

- ↑ Keith M. Brown, "Early Modern Scottish History - A Survey," Scottish Historical Review (April 2013 Supplement), Vol. 92, pp. 5–24.

- ↑ Michael Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (2007) excerpt.

- ↑ James described Cecil as "king there in effect". Croft, p 48.

- ↑ Cecil wrote that James should "secure the heart of the highest, to whose sex and quality nothing is so improper as either needless expostulations or over much curiosity in her own actions, the first showing unquietness in yourself, the second challenging some untimely interest in hers; both which are best forborne." Willson, pp 154–155.

- ↑ Willson, p 155.

- ↑ Croft, p 49; Willson, p 158.

- ↑ Gijs Rommelse, "The role of mercantilism in Anglo‐Dutch political relations, 1650–74." Economic History Review 63#3 (2010): 591-611.

- ↑ James Rees Jones, The Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century (1996) online

- ↑ J.H. Plumb, England in the Eighteenth Century (1950)

- ↑ Roy Porter, English Society in the Eighteenth Century (2nd ed. 1990).

- ↑ Paul Langford, Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Very Short Introduction (2005).

- ↑ Anthony, Pagden (1998). The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 441.

- ↑ Anthony, Pagden (2003). Peoples and Empires: A Short History of European Migration, Exploration, and Conquest, from Greece to the Present. Modern Library. p. 90.

- ↑ James Falkner, The War of the Spanish Succession 1701 - 1714 (2015).

- ↑ Bob Harris, "The Anglo Scottish Treaty of Union, 1707 in 2007: Defending the Revolution, Defeating the Jacobites," Journal of British Studies Jan. 2010, Vol. 49, No. 1: 28–46. in JSTOR

- ↑ Karin Bowie, "Popular Resistance and the Ratification of the Anglo-Scottish Treaty of Union," Scottish Archives, 2008, Vol. 14, pp 10–26

- ↑ The Jacobite Relics of Scotland

- ↑ Allan I. Macinnes, "Treaty Of Union: Voting Patterns and Political Influence," Historical Social Research, 1989, Vol. 14 Issue 3, pp 53–61

- ↑ Bruce Lenman, The Jacobite Risings in Britain, 1689–1746 (1980)

- ↑ Eveline Cruickshanks, "Jacobites, Tories and James III", Parliamentary History, July 2002, Vol. 21 Issue 2, p247-53

- ↑ Julian Hoppit, A Land of Liberty?: England 1689–1727 (2000) p 344

- ↑ Hoppit, A Land of Liberty?: England 1689–1727 (2000) pp 334–38

- ↑ Julian Hoppit, "The Myths of the South Sea Bubble," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Dec 1962, Vol. 12 Issue 1, pp 141–165

- ↑ Robert M. Kozub, "Evolution of Taxation in England, 1700–1850: A Period of War and Industrialization," Journal of European Economic History, Fall 2003, Vol. 32 Issue 2, pp 363–388

- ↑ John Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State, 1688–1783 (1990)

- ↑ Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1989) pp 80–84

- ↑ Anthony, Pagden (2003). Peoples and Empires: A Short History of European Migration, Exploration, and Conquest, from Greece to the Present. Modern Library. p. 91.

- ↑ Niall, Ferguson (2004). Empire. Penguin. p. 73.

- ↑ Anthony, Pagden (1998). The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 92.

- ↑ James, Lawrence (2001). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. p. 119.

- ↑ James, Lawrence (2001). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. p. 152.

- ↑ Simon Devereaux, "The Historiography of the English State During 'The Long Eighteenth Century' Part Two - Fiscal-Military and Nationalist Perspectives." History Compass (2010) 8#8 pp 843-865.

- ↑ Oliver MacDonagh, "The Nineteenth-Century Revolution in Government: A Reappraisal." The Historical Journal 1#1 (1958): 52-67.

- ↑ Edward Higgs, Identifying the English: a history of personal identification 1500 to the present (2011)

- ↑ John Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State, 1688-1783 (1990)

- ↑ Aaron Graham, The British Fiscal-military States, 1660-c. 1783 (2015).

Further reading

- Black, J. B. The Reign of Elizabeth, 1558–1603 (Oxford History of England) (1959) excerpt and text search

- Clark, George Norman. The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714 (Oxford History of England) (1956), standard scholarly survey

- Davies, Godfrey. The Early Stuarts, 1603–1660 (Oxford History of England) (1959).

- Elton, G.R. Modern Historians on British History 1485-1945: A Critical Bibliography 1945-1969 (1970) excerpt, highly useful bibliography of 490+ scholarly books, articles and book reviews published before 1970 that deal with 1485-1815.

- Guy, John. Tudor England (1988), a standard scholarly survey

- Hoppit, Julian. A Land of Liberty?: England 1689–1727 (New Oxford History of England) (2002), standard scholarly survey; excerpt and text search

- Kishlansky, Mark A. A Monarchy Transformed: Britain, 1603–1714 (Penguin History of Britain) (1997), a standard scholarly survey; excerpt and text search

- Langford, Paul. Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Very Short Introduction (2005).

- Langford, Paul. A Polite and Commercial People: England 1727–1783 (New Oxford History of England) (1994), a standard scholarly survey; 803pp

- Mackie, J. D. The Earlier Tudors: 1485–1558 (The Oxford History of England) (1957).

- Marshall, Dorothy, Eighteenth Century England 1714 - 1784 (1962)

- Ogg, David. Europe in the Seventeenth Century (1st ed, 1925; 8th ed, 1960).

- Ogg, David. England in the Reigns of James II and William III (2nd ed. 1957)

- Ogg, David. England in the Reign of Charles II (2 vol 2nd ed. 1955)

- Palliser, D. M. The Age of Elizabeth: England Under the Later Tudors, 1547–1603 (2nd ed. 1992), primarily social & economic history

- William, Basil and C. H. Stuart. The Whig Supremacy, 1714–1760 (Oxford History of England) (1962), older scholarly survey

- Watson, J. Steven. The Reign of George III, 1760–1815 (Oxford History of England) (1960), a standard scholarly survey

- Williams, Penry. The Later Tudors: England, 1547–1603 (New Oxford History of England) (1995), a standard scholarly survey

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Early Modern period. |