1763 in paleontology

|

|

|---|

- ... 1753

- 1754

- 1755

- 1756

- 1757

- 1758

- 1759 ...

- 1760

- 1761

- 1762

- 1763

- 1764

- 1765

- 1766

- ... 1767

- 1768

- 1769

- 1770

- 1771

- 1772

- 1773 ...

|

|

|

|

Paleontology or palaeontology (from Greek: paleo, "ancient"; ontos, "being"; and logos, "knowledge") is the study of prehistoric life forms on Earth through the examination of plant and animal fossils.[1] This includes the study of body fossils, tracks (ichnites), burrows, cast-off parts, fossilised feces (coprolites), palynomorphs and chemical residues. Because humans have encountered fossils for millennia, paleontology has a long history both before and after becoming formalized as a science. This article records significant discoveries and events related to paleontology that occurred or were published in the year 1763.

Fossils

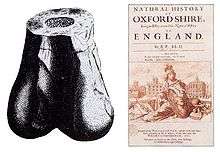

- The end of a Megalosaurus thighbone, previously misinterpreted by Robert Plot to be the remains of an elephant brought to Britain by the Romans, is subject to further confusion when Richard Brookes publishes a paper naming it Scrotum humanum. Although he meant this name metaphorically to describe the bone's appearance, this idea is taken seriously by French philosopher Jean-Baptiste Robinet, who believed that nature formed fossils in mimicry of portions of the human anatomy- such as the scrotum.[2]

Dinosaurs

Newly named dinosaurs

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Scrotum humanum." |

|

|

|

References

- ↑ Gini-Newman, Garfield; Graham, Elizabeth (2001). Echoes from the past: world history to the 16th century. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd. ISBN 9780070887398. OCLC 46769716.

- ↑ Farlow, James O.; M. K. Brett-Surmann (1999). The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-253-21313-4.