171st Tunnelling Company

| 171st Tunnelling Company | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | World War I |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Royal Engineer tunnelling company |

| Role | military engineering, tunnel warfare |

| Nickname(s) | "The Moles" |

| Engagements |

World War I Hill 60 Battle of Messines Battle of Passchendaele Battle of the Lys |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Henry M. Hudspeth |

The 171st Tunnelling Company was one of the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers created by the British Army during World War I. The tunnelling units were occupied in offensive and defensive mining involving the placing and maintaining of mines under enemy lines, as well as other underground work such as the construction of deep dugouts for troop accommodation, the digging of subways, saps (a narrow trench dug to approach enemy trenches), cable trenches and underground chambers for signals and medical services.[1]

Background

By January 1915 it had become evident to the BEF at the Western Front that the Germans were mining to a planned system. As the British had failed to develop suitable counter-tactics or underground listening devices before the war, field marshals French and Kitchener agreed to investigate the suitability of forming British mining units.[2] Following consultations between the Engineer-in-Chief of the BEF, Brigadier George Fowke, and the mining specialist John Norton-Griffiths, the War Office formally approved the tunnelling company scheme on 19 February 1915.[2]

Norton-Griffiths ensured that tunnelling companies numbers 170 to 177 were ready for deployment in mid-February 1915. In the spring of that year, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and The Bluff which required the deployment of new drafts of tunnellers for several months after the formation of the first eight companies. The lack of suitably experienced men led to some tunnelling companies starting work later than others. The number of units available to the BEF was also restricted by the need to provide effective counter-measures to the German mining activities.[3] To make the tunnels safer and quicker to deploy, the British Army enlisted experienced coal miners, many outside their nominal recruitment policy. The first nine companies, numbers 170 to 178, were each commanded by a regular Royal Engineers officer. These companies each comprised 5 officers and 269 sappers; they were aided by additional infantrymen who were temporarily attached to the tunnellers as required, which almost doubled their numbers.[2] The success of the first tunnelling companies formed under Norton-Griffiths' command led to mining being made a separate branch of the Engineer-in-Chief's office under Major-General S.R. Rice, and the appointment of an 'Inspector of Mines' at the GHQ Saint-Omer office of the Engineer-in-Chief.[2] A second group of tunnelling companies were formed from Welsh miners from the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the Monmouthshire Regiment, who were attached to the 1st Northumberland Field Company of the Royal Engineers, which was a Territorial unit.[4] The formation of twelve new tunnelling companies, between July and October 1915, helped to bring more men into action in other parts of the Western Front.[3]

Most tunnelling companies were formed under Norton-Griffiths' leadership during 1915, and one more was added in 1916.[1] On 10 September 1915, the British government sent an appeal to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand to raise tunnelling companies in the Dominions of the British Empire. On 17 September, New Zealand became the first Dominion to agree the formation of a tunnelling unit. The New Zealand Tunnelling Company arrived at Plymouth on 3 February 1916 and was deployed to the Western Front in northern France.[5] A Canadian unit was formed from men on the battlefield, plus two other companies trained in Canada and then shipped to France. Three Australian tunnelling companies were formed by March 1916, resulting in 30 tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers being available by the summer of 1916.[1]

Unit history

Formation

171st Tunnelling Company was formed between February and March 1915 of a small number of specially enlisted miners, with troops selected from the Monmouthshire Siege Company of Royal Engineers.[1]

Hill 60/Messines

171st Tunnelling Company was first employed in March 1915 in the Hill 60/Bluff areas at Ypres.[1] The Germans held the top of Hill 60 from 16 December 1914 to 17 April 1915, when it was captured briefly by the British 5th Division after the explosion of five mines under the German lines by the Royal Engineers. The early underground war in the area had involved both the 171st and 172nd Tunnelling Company.[6]

In July 1915, 171st Tunnelling Company moved to Ploegsteert and commenced mining operations near St Yves at the southern end of the Messines ridge.[1] The four deep mines at St Yves, charged with a combined load of 146,000 pounds (66,000 kg) of ammonal, formed part of the mine galleries that were dug by the British 171st, 175th, 250th, 1st Canadian, 3rd Canadian and 1st Australian Tunnelling companies as part of the prelude to the Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917), while the British 183rd, 2nd Canadian and 2nd Australian Tunnelling companies built underground shelters in the Second Army area.[7]

In December 1915, 171st Tunnelling Company began work on the deep mine at Trench 127 at St Yves. The mine consisted of two chambers (Trench 127 Left, Right) with a shared gallery. The name indicates the British lines where the initial shaft was dug, not where the mine was placed under the German positions. The shaft was completed to a depth of 25 metres (82 ft) within four weeks, however after driving a 310 metres (1,020 ft) gallery the Royal Engineers faced a sudden inrush of quicksand and a concrete dam had to be constructed. A new attempt was made, and by April 1916 the Trench 127 mine was ready, with the ammonal charges over 400 metres (1,300 ft) away from the initial shaft.[8]

At the end of January 1916, 171st Tunnelling Company began mining operations at La Petite Douve Farm.[9] The farm, located next to the road from Messines to Ploegsteert Wood, was enclosed by a German trench system known as ULNA. Also at this point was a junction on the narrow gauge railway system which ran from the forward areas of Messines to the rear areas around Nieuwkerke. This operation was characterized by setbacks. Difficult geology lead to two mines being abandoned before completion, and after a charge of 23,000 kilograms (50,000 lb) of ammonal had been put in place beneath the farm, the gallery was discovered by a German counter-mining operation on 24 August 1916.[10] Three days later the German miners blew a heavy charge, which shattered about 120 metres (400 ft) of the main gallery and killed four men engaged in repairs. This camouflet wrecked the British gallery completely and forced the Royal Engineers to abandon the tunnel,[11] which then quickly flooded.[10]

At the end of February 1916, 171st Tunnelling Company began work on the deep mine at Trench 122 at St Yves. The mine consisted of two chambers (Trench 122 Left, Right) with a shared gallery. The name indicates the British lines where the initial shaft was dug, due west of where the crater is today. The area was dominated by a complex of German trenches and by mid-May first charge of 9,100 kilograms (20,000 lb) of ammonal was in place at Trench 122 Left. Another shaft (Trench 122 Right) was started part way along the original tunnel and after another 200 metres (660 ft), a charge of 40,000 lbs of ammonal was placed by the Royal Engineers beneath the ruins of Factory Farm which sat on the German front line.[8]

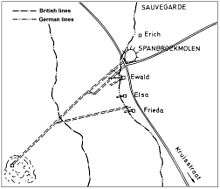

In April 1916, 171st Tunnelling Company moved to the Spanbroekmolen/Douve sector facing the Messines ridge.[1] At Spanbroekmolen, 171st Tunnelling Company took over from 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company and extended the work to the German lines, driving the tunnel forward by 523 metres (1,717 ft) in seven months[12] until it was beneath the powerful German position. At the end of June 1916 the charge of 41,000 kilograms (91,000 lb) of ammonal in 1,820 waterproof tins was complete, the largest yet laid by the British. With the mine complete, the British selected two additional objectives to be attacked near Spanbroekmolen, Rag Point and Hop Point, which were 820 metres (2,700 ft) and 1,100 metres (3,500 ft) from the main tunnel. A branch was started and inclined down to 37 metres (120 ft) depth. By mid-February 1917 the branch had been driven 350 metres (1,140 ft) and passed the German lines.[11] At that point, the German counter mining activities damaged 150 metres (500 ft) of the branch gallery and some of the main tunnel. The British decided to abandon the branch gallery because aggressive counter-mining would alert the Germans to the presence of a deep-mining scheme. On 3 March the Germans blew the main tunnel with a heavy charge laid from their Ewald shaft, leaving it beyond repair and resulting in it being cut off for three months.[11] The British started a new gallery alongside the old main tunnel which after 357 metres (1,172 ft) cut into the original workings. Mining was greatly hampered by the influx of gas, several miners being overcome by the fumes, but eventually – and only a few hours before the appointed time of detonation at 03:10 a.m. on 7 June 1917 – the ammonal charge was ready again and secured by 120 metres (400 ft) of tamping with sandbags and a primer charge of 450 kilograms (1,000 lb) of dynamite. The Spanbroekmolen mine exploded 15 seconds late, killing a number of British soldiers from the 36th (Ulster) Division, some of whom are buried at Lone Tree Cemetery nearby.[12]

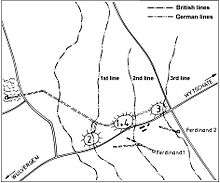

While employed at Spanbroekmolen, 171st Tunnelling Company also took over work on the nearby deep mines at Kruisstraat. Work there was begun by 250th Tunnelling Company in December 1915, passed to 182nd Tunnelling Company, then to 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company and 175th Tunnelling Company, which took charge in April 1916. When the gallery reached 320 metres (1,051 ft) it was handed over to 171st Tunnelling Company. At 489 metres (1,605 ft) a charge of 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) of ammonal was laid and at the end of a small branch of 166 feet (51 m) to the right a second charge of 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) was placed under the German front line. This completed the original plan, but it was decided to extend the mining to a position under the German third line. Despite meeting clay and being inundated with water underground which necessitated the digging of a sump, they managed to complete a gallery stretching almost half a mile from the shaft in just two months, and a further charge of 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) of ammonal was placed. This tunnel was the longest of any of the Messines mines. In February 1917, German countermeasures necessitated some repair to one of the chambers and the opportunity was taken to place a further charge of 8,800 kilograms (19,500 lb) marking a total of four mines, all of which were ready by 9 May 1917.[13]

At the end of January 1917, the 171st Tunnelling Company began work on the deep mine at Ontario Farm. The ground at the site selected for this mine proved very difficult as much of it was sandy clay. The miners began to dig at Boyle's Farm which is just on the southern side of the main road (Mesenstraat/Nieuwkerkestraat) passing by. The shaft went down 30 metres (98 ft) and pumps were installed to bring air down and water out of the mine. After tunnelling forward, the miners broke into blue clay, extending the depth to some 40 metres (130 ft). After driving the gallery almost 200 metres (660 ft) forward, the flooding was so bad that a dam had to be constructed and a new gallery started. Despite these obstacles, the tunnellers arrived under Ontario Farm at the end of May 1917 and installed the 27,000 kilograms (60,000 lb) ammonal charge with a day to spare.[14] When it was detonated on 7 June 1915, the mine did not produce a crater but left a shallow indentation in the soft clay; the shock wave did great damage to the German position.[15][16] The explosion caught two battalions of the 17th Bavarian Infantry Regiment during a relief, half of which were "as good as annihilated".[17]

The mines at Messines were detonated on 7 June 1917, creating 19 large craters.

Vampire dugout

The 171st Tunnelling Company stayed in the Ypres Salient and moved near the village of Zonnebeke, where it constructed the Vampire dugout (known locally as the Vampyr dugout). Vampire was built to house a brigade headquarters of up to 50 men and one senior commanding officer.[18] Located close to Polygon Wood, it was named after the supply soldiers whose mission was to come out at night to re-supply troops in the front line.[19]

At the end of the Third Battle of Ypres/Battle of Passchendaele (31 July–10 November 1917), having retaken Passchendaele ridge, the British were left with little natural shelter from the former woods and farms. The artillery of both sides had literally flattened the landscape. Needing shelter for their troops, the Allied High Command in January 1918 moved 25,000 specialist tunnellers and 50,000 attached infantry who had been preparing and taking part in the Battle of Messines north in the Ypres Salient. There they dug almost 200 independent and connected structures at depths of 30 metres (98 ft) into the blue clay, which could accommodate from 50 men, to the largest at Wieltje and Hill 63 which could house 2,000.[20] The level of the activity can be gauged by the fact that by March 1918, more people lived underground in the Ypres area than reside above ground in the town today. Connected by corridors measuring 6.5 feet (2.0 m) high by 4 feet (1.2 m) wide, they were fitted with water pumps to deal with the high groundwater table.[21]

Created 14 metres (46 ft) below Flanders by the 171st Tunnelling Company,[22] and dug over a period of four months, the engineers used I beams and reclaimed railway line in a D-type sett structure. This was then further reinforced, using stepped wooden horizontal beams.[23] The Vampire dugout became operational from early April 1918, first housing the 100th Brigade of the British 33rd Division, then the 16th King's Royal Rifle Corps and then the 9th Battalion Highland Light Infantry Regiment.[24] After only a few weeks, the dugout was lost when the Germans undertook the Battle of the Lys in April 1918. It was recaptured in September 1918, when its last occupants became the 2nd Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment.

Zonnebeke church dugout

In March 1918, the 171st Tunnelling Company constructed a deep dugout in the centre of Zonnebeke, located directly beneath the ruins of the parish church. This dugout was only discovered after the Second World War during archaeological excavations of the Augustinian abbey. Today the outline of this dugout is marked in an archaeological garden within the church grounds, and a model of the church dugout can be seen at the "Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917" in Zonnebeke.[25]

Spring Offensive

Shortly after the completion of the Vampire dugout, 171st and several other tunnelling companies (173rd, 183rd, 184th, 255th, 258th and 3rd Australian) were forced to move from their camps at Boeschepe in April 1918, when the enemy broke through the Lys positions during the Spring Offensive. These units were then put on duties that included digging and wiring trenches over a long distance from Reningelst to near Saint-Omer.[1] The operation to construct these fortifications between Reningelst and Saint-Omer was carried out jointly by the British 171st, 173rd, 183rd, 184th, 255th, 258th, 3rd Canadian and 3rd Australian Tunnelling Companies.

See also

References

An overview of the history of 171st Tunnelling Company is also available in Robert K. Johns, Battle Beneath the Trenches: The Cornish Miners of 251 Tunnelling Company RE, Pen & Sword Military 2015 (ISBN 978-1473827004), p. 214 see online

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Tunnelling Companies RE Archived May 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., access date 25 April 2015

- 1 2 3 4 "Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths (1871–1930)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- 1 2 Peter Barton/Peter Doyle/Johan Vandewalle, Beneath Flanders Fields - The Tunnellers' War 1914-1918, Staplehurst (Spellmount) (978-1862272378) p. 165.

- ↑ "Corps History – Part 14: The Corps and the First World War (1914–18)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ↑ Anthony Byledbal, "New Zealand Tunnelling Company: Chronology" (online Archived July 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.), access date 5 July 2015

- ↑ Holt & Holt 2014, p. 247.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, p. 37–38.

- 1 2 Holt & Holt 2014, p. 251.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 153.

- 1 2 Holt & Holt 2014, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Jones 2010, p. 151.

- 1 2 Holt & Holt 2014, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Holt & Holt 2014, p. 195.

- ↑ Holt & Holt 2014, p. 249.

- ↑ "Messines". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "Photo gallery: Battle of Messines Ridge". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 162.

- ↑ Robert Hall (2007-02-23). "Uncovering the secrets of Ypres". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "Vampire dugout". polygonwood.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917". GreatWar.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ Jasper Conning (2007-08-27). "First World War tunnels to yield their secrets". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "Corps History - Part 14: The Corps and the First World War (1914-18)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "Vampire Dugout" (PDF). polygonwood.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "Scots' World War One Shelter Discovered". Daily Record. 2008-02-16. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ Zonnebeke Church Dugout wordt niet toegankelijk voor publiek, 04/11/2010, access date 9 July 2015

Further reading

- Alexander Barrie. War Underground – The Tunnellers of the Great War. ISBN 1-871085-00-4.

- The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914 -1919, – MILITARY MINING.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914-1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Arthur Stockwin (ed.), Thirty-odd Feet Below Belgium: An Affair of Letters in the Great War 1915-1916, Parapress (2005), ISBN 978-1-89859-480-2 (online).

External links

- List of tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers, with short unit histories

- 'Born Fighters: Who were the Tunnellers?' Conference paper by Simon Jones.